Already now, he went on, Americans should think about the attitudes they would adopt after the guns fell silent: “Weary of war, we may fall ready victims to post-war cynicism and disillusionment, as we did at the end of the last war.” It would be a dreadful mistake, for victory would be no less consequential for being incomplete. “Even if we may not win all for which we strive—even if we win only a small part—that small part will mean progress forward and that indeed makes our cause a worthy one.” Then a ringing finale: Americans must strive, like their forebears, to reach for that goal, to “renew that heritage” and maintain that idealism, even in the face of great odds. “The sacrifice is not too great,” the young ensign declared. “As young men, it is, after all, for our own future that we fight. And so with a firm confidence and belief in that future, let us go forward to victory.”58

Brothers in the service: Lieutenant Junior Grade Jack and Ensign Joe Junior, late 1942.

Would he himself get to contribute to that good fight? It seemed doubtful, given his infirmities, but through the spring he persistently lobbied for combat service. In late July 1942, there finally came welcome news: he was being transferred to midshipmen’s school at Northwestern University, in suburban Chicago. On the way there, he stopped once more in Washington and called Inga. She again refused to sleep with him but agreed to meet the next day. His physical condition shocked her. In a phone call to a friend monitored by the FBI, she said, “He is going on active sea duty. Only you know, his back—he looks like a limping monkey from behind. He can’t walk at all. That’s ridiculous, sending him off to sea duty.”59

One wonders about the mood overall of the young men who reported on that first day of midshipmen’s training. The war news had been mostly grim since Pearl Harbor. In the months after the attack, the area of Japanese conquest spread like spilled ink on a map—Hong Kong and British Malaya fell in December 1941, followed by Singapore in February, then Burma and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), then the Philippines. The U.S. bases at Guam and Wake Island also succumbed.60 Meanwhile, China grew weaker and India appeared threatened, as did Australia. In the Atlantic, German submarines were sinking ships faster than the Allies could replace them (in the first months after America’s entry into the war, the U-boats sank 216 vessels, some so close to U.S. shores that people could see the glow of burning hulls), while on land the German forces resumed their advances in Russia and the British defense of Egypt faltered. By the spring of 1942, the Axis powers controlled more than a third of the world’s population and mineral resources. It seemed only a matter of time before the Wehrmacht would be at the gates of India, to be met there by ally Japan, advancing from the east. In June, Jack and his mates in Charleston cheered the epic U.S. naval victory against Japan in the Battle of Midway, but the decisive nature of that encounter would become clear only in time.61

Despite the Japanese advances in the Pacific, Roosevelt’s war strategy was “Europe First,” a commitment he affirmed in a conference with Winston Churchill in Washington a few weeks after Pearl Harbor. In the president’s view and those of his chief advisers, Germany represented a greater danger to the United States than did Japan. If Hitler conquered Stalin’s Soviet Union, they felt certain, he would pose an acute existential threat to U.S. security. American planners also worried that the USSR, suffering almost unimaginable losses in the face of the Wehrmacht’s ferocious power, might pursue a separate peace with Nazi Germany and consequently shred the Allied coalition. Washington must therefore work first with Britain and the Soviet Union to defeat the Germans, then confront an isolated Japan.

But there would still be plenty to do in the Far East in the short term, and it was the likely destination for Ensign Kennedy, given the heavy naval effort there—provided he could get through his training program. He pronounced himself less than impressed by the curriculum and the facilities. “This goddamn place is worse than Choate,” he informed Lem Billings, “and Lt. J. makes Jack Maher look like a good guy—well maybe not a good guy, but a better guy. But as F.D.R. always says, this thing is bigger than you or I—it’s global—so I’ll string along.” Jack added that he wanted to command one of the motor torpedo boats, or PTs (for “patrol torpedo”), as they were popularly known. “The requirements are very strict physically—you have to be young, healthy and unmarried—and as I am young and unmarried, I’m trying to get in. If I last we get command of a torpedo boat—and are sent abroad—where I don’t know.”62

Jack’s desire for a PT command likely owed something to the remarkable publicity a handful of torpedo boats in the Philippines had received in the United States after the Japanese invasion. The papers were full of tales of the heroic deeds of these small craft and their skippers, in particular Lieutenant Commander John Bulkeley, who had won a Congressional Medal of Honor for extracting General Douglas MacArthur from the fighting on the Bataan Peninsula, in the Philippines, in March and transporting him back through five hundred miles of Japanese-dominated waters to safety. Bulkeley, a self-aggrandizing but extremely skillful promoter of the PTs, had exaggerated mightily in selling their importance to FDR and the American public. Jack bought into the hoopla. His natural skepticism made him dubious that the lightly armed vessels were inflicting as much damage on the Japanese as Bulkeley claimed, but there was an undeniable swashbuckling quality to the PT missions that appealed to him. The boats had glamour, pure and simple. And if commanding a torpedo boat got him away from the tedium of office work or—he imagined—toiling as a subordinate on a destroyer or aircraft carrier, so much the better.

And there was, one imagines, one additional reason for his attraction: on a summer day the previous year, Jack had sailed his beloved sloop Victura from Hyannis Port across Nantucket Sound and into Edgartown, on Martha’s Vineyard. When he entered the harbor, he spied a sleek new type of vessel he had not seen before: a PT boat the Navy had brought from Newport and put on display. Mesmerized by her trim lines and powerful aura, Jack had the urge in that instant to hop on board, take the wheel, and open the throttles wide. Now perhaps he could get his opportunity.63

Then again, the chances of Jack Kennedy becoming a PT commander should have been vanishingly small, even leaving aside his bad back. The competition was fierce, with more than a thousand applicants for fifty slots. Yet Jack was tapped, thanks in large measure to an assist from his father, who invited Bulkeley to a leisurely lunch at the Plaza Hotel, in New York, and asked him if he had the power to get Jack into a torpedo boat. Bulkeley said he did, and promised to interview Jack when he returned to Northwestern. Joe expressed his thanks, adding that he hoped his son would be sent someplace that wasn’t “too deadly.” Jack performed well in the ensuing interview, impressing Bulkeley and Lieutenant Commander John Harllee with his obvious intelligence and leadership qualities, and with the fact that he had grown up around boats and was an expert sailor who had won a regatta for Harvard. Questions regarding his physical health did not come up.64

To Harllee’s mind there was nothing wrong with Joe Kennedy lobbying on his son’s behalf: “There’s a lot of people in America who use political influence to keep out of combat,” he told a later interviewer, “but Jack Kennedy used it to get into combat!”65

VI

On October 1, 1942, Jack Kennedy commenced an eight-week PT officer training course on Narragansett Bay in Melville, Rhode Island. He was now a lieutenant, junior grade, which meant he again outranked his brother Joe, who had been promoted to ensign. And he was suffering. “Jack came home,” Joe Senior wrote to Joe Junior after Jack had spent some days in Hyannis Port on his way to his new assignment, “and between you and me is having terrific trouble with his back….I don’t see how he can last a week in that tough grind of torpedo boats, and what he wants to do…is to be operated on and then have me fix it so he can get back in that service when he gets better.” If this was indeed Jack’s objective, he didn’t follow through: he began his Melville training on schedule a few days later. His only concession to his aches and pains was a piece of plywood he procured at a local lumberyard to put under his mattress.66

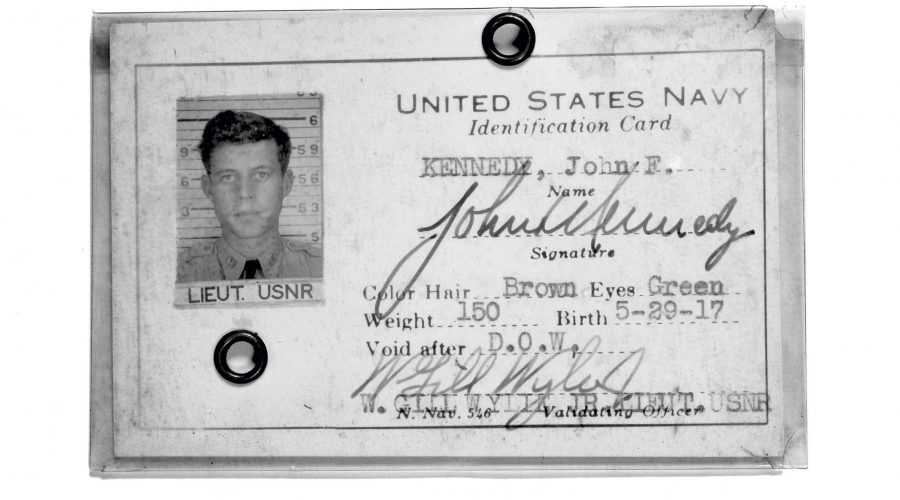

Jack’s Navy ID card.

“He was in pain,” a roommate remembered, “he was in a lot of pain, he slept on that damn plywood board all the time and I don’t remember when he wasn’t in pain.” But Jack relished the training, most of it in Elco motor torpedo boats of the PT 103 class. Low and squat and measuring eighty feet in length, with a twenty-foot, eight-inch beam, the vessels had wooden hulls and were powered by three twelve-cylinder Packard engines, each with 1,350 horsepower, allowing a speed of forty-three knots. Each carried four twenty-one-inch torpedoes and four .50-caliber machine guns on two twin turrets, as well as depth charges, rocket launchers, and mine racks. A normal complement was two to three officers and nine men. Jack, comfortable on the sea from his many years of sailing off the Cape, loved handling the boats, and he loved their speed. Most of all, he cherished the freedom they brought. “This job on these boats is really the great spot of the Navy,” he crowed to Lem, “you are your own boss and it’s like sailing around in the old days.”67

Even the evident inadequacies in the training—the men received little instruction on the handling and use of torpedoes and virtually no nighttime training, though it was well known that the PT boats were too vulnerable to enemy aircraft to operate except under cover of darkness—didn’t deter him, and he impressed his mates with his seafaring skills and intelligence as well as his self-deprecating wit and lack of pretension. He was “receptive to everybody,” recalled Sim Efland, a roommate, and in no way “a stuck-up individual” with a superior attitude. “When I think of my association with Jack: he associated with people no matter who—and that was unusual. Here I was, a southerner, and all these other people from Harvard, Yale, and these other places would give me hell. Say, ‘We can’t understand what you’re talking about, you don’t talk like we do, you talk too slow,’ or something. Now Jack didn’t do that. He respected people. He was also a good analyst, I felt….I had a lot of respect for him.”68

Another roommate, Fred Rosen, likewise held Jack in high regard, notwithstanding one rocky episode in their Quonset hut. As Rosen recalled in an interview many years afterwards, Jack one evening observed casually that Jews were all “going into the Quartermaster Corps” in order to avoid combat. Rosen, who was Jewish, bristled. “They must be good at trigonometry, Jack,” he shot back. “Why?” “Because the navy’s navigators are drawn from the Quartermaster Corps.” An extended exchange followed, in which Rosen persuaded Jack to recant his anti-Semitic assertion. To Rosen, Jack’s casual, unthinking prejudice likely owed much to his father’s pontifications around the family dining table over the years, and he admired Jack all the more for his willingness to admit his error.69

At the end of the eight weeks, in late November, John Harllee, the senior instructor, graded Jack superior in boat handling, good in engineering, and “very willing and conscientious.” So impressed was Harllee that he selected Jack to be a PT instructor, which meant he would remain stateside for a minimum of six additional months instead of getting a combat assignment. (It’s possible there was more involved in the decision than Jack’s stellar performance: his father had made clear to Bulkeley and perhaps to Harllee his anxiety about seeing his sons in combat.) Far from being flattered or relieved at the news, Jack reacted angrily, insisting that he be sent overseas to one of the war zones. (He was being “shafted,” he said to his Navy pals, who promptly gave him the nickname “Shafty.”) Harllee refused to bend. “I told him that we needed people of his ability for instructors. I absolutely insisted that he remain, which made him extremely unhappy.”70

Jack did not give up. With the help of his grandfather Honey Fitz, he arranged a one-on-one meeting with Massachusetts senator David I. Walsh, the chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee. Walsh liked what he saw—“Frankly, I have not met a young man of his age in a long time who has impressed me so favorably,” he wrote to Honey Fitz. “He has a fine personality, energetic and outstanding qualities of leadership, and with all a becoming modesty”—and urged the Navy Department to transfer Jack to a combat zone.71 The appeal evidently had an effect, for in January 1943 the young officer was detached from his Melville duties and ordered to take four boats to Jacksonville, Florida, and await further instructions on his next assignment. En route to Florida, one of the boats ran aground and Jack dove into the freezing water to clear a towrope that had become tangled in a propeller. He became ill and was laid up in Morehead City, North Carolina, with a temperature of 103, but soon recovered and rejoined his flotilla in Jacksonville. Expecting a combat assignment (“Am on my way to war,” he wrote to brother Bobby, who was in his final year of prep school), Jack learned, to his annoyance, that he was being sent not to a war theater but to patrol duty at the Panama Canal. He again turned to Senator Walsh, who again wrote on his behalf.72

How to explain this unrelenting determination to see military action? More than a few fellow draftees, after all, whatever their subsequent claims to the contrary, were quite content to wear the uniform in safer locales, far from enemy concentrations—locales like, well, Panama. Was it because he felt invincible, as young men often do? This seems unlikely, given his checkered health history and that, even this early in the war, he was writing sober letters about college chums who had been killed or were missing in action. Did he want a war record on which he could later run for political office? Again, maybe, though it seems far-fetched to believe that this calculation drove him, even if one folds in a perceived need to overcome any lingering “Kennedys are cowards” whispers arising from his father’s actions in London during the Blitz. No, the real answer seems more basic: Jack’s long immersion in world politics, through reading and writing and travel, together with the inspirational exhortations of people like James Forrestal, John Bulkeley, and Clare Boothe Luce, had convinced him that this was a crusade against totalitarianism, in which the future of Western civilization was at stake and in which all must do their part. Thus he applauded Lem Billings (who had been rejected by the Army and the Navy because of his poor eyesight) for getting himself close to combat as an ambulance driver in North Africa, and Rip Horton for contemplating switching from the Quartermaster Corps to a paratrooper role. And thus he cheered brother Joe’s efforts to become a Navy flier.73

Senator Walsh’s intervention did the trick. On March 6, 1943, Lieutenant John Fitzgerald Kennedy boarded the troop carrier Rochambeau on pier 34 in San Francisco, bound first for San Diego for a troop pickup and then for the New Hebrides, eleven hundred miles northeast of Australia. He was on his way to the war.