RULE 11

DO NOT BOTHER CHILDREN WHEN THEY ARE SKATEBOARDING

DANGER AND MASTERY

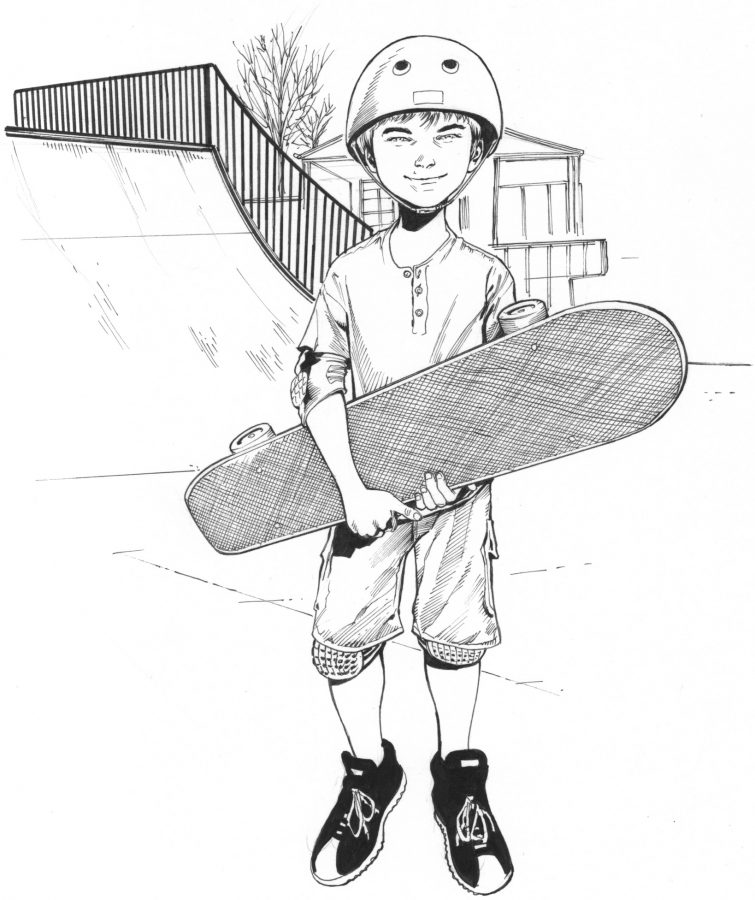

THERE WAS A TIME WHEN KIDS skateboarded on the west side of Sidney Smith Hall, at the University of Toronto, where I work. Sometimes I stood there and watched them. There are rough, wide, shallow concrete steps there, leading up from the street to the front entrance, accompanied by tubular iron handrails, about two and a half inches in diameter and twenty feet long. The crazy kids, almost always boys, would pull back about fifteen yards from the top of the steps. Then they would place a foot on their boards, and skate like mad to get up some speed. Just before they collided with the handrail, they would reach down, grab their board with a single hand and jump onto the top of the rail, boardsliding their way down its length, propelling themselves off and landing—sometimes, gracefully, still atop their boards, sometimes, painfully, off them. Either way, they were soon back at it.

Some might call that stupid. Maybe it was. But it was brave, too. I thought those kids were amazing. I thought they deserved a pat on the back and some honest admiration. Of course it was dangerous. Danger was the point. They wanted to triumph over danger. They would have been safer in protective equipment, but that would have ruined it. They weren’t trying to be safe. They were trying to become competent—and it’s competence that makes people as safe as they can truly be.

I wouldn’t dare do what those kids were doing. Not only that, I couldn’t. I certainly couldn’t climb a construction crane, like a certain type of modern daredevil, evident on YouTube (and, of course, people who work on construction cranes). I don’t like heights, although the twenty-five thousand feet to which airliners ascend is so high that it doesn’t bother me. I have flown several times in a carbon fibre stunt plane—even doing a hammerhead roll—and that was OK, although it’s very physically and mentally demanding. (To perform a hammerhead roll, you pilot the plane straight up vertically, until the force of gravity makes it stall. Then it falls backwards, corkscrewing, until eventually it flips and noses straight down, after which you pull out of the dive. Or you don’t do another hammerhead roll.) But I can’t skateboard—especially down handrails—and I can’t climb cranes.

Sidney Smith Hall faces another street on the east side. Along that street, named St. George—ironically enough—the university installed a series of rough, hard-edged, concrete plant boxes, sloping down to the roadway. The kids used to go out there, too, and boardslide along the box edges, as they did along the concrete surround of a sculpture adjacent to the building. That didn’t last very long. Little steel brackets known as “skatestoppers” soon appeared, every two or three feet, along those edges. When I first saw them, I remembered something that happened in Toronto several years previously. Two weeks before elementary school classes started, throughout the city, all the playground equipment disappeared. The legislation governing such things had changed, and there was a panic about insurability. The playgrounds were hastily removed, even though they were sufficiently safe, grandfathered re their insurability, and often paid for (and quite recently) by parents. This meant no playgrounds at all for more than a year. During this time, I often saw bored but admirable kids charging around on the roof of our local school. It was that or scrounge about in the dirt with the cats and the less adventurous children.

I say “sufficiently safe” about the demolished playgrounds because when playgrounds are made too safe, kids either stop playing in them or start playing in unintended ways. Kids need playgrounds dangerous enough to remain challenging. People, including children (who are people too, after all) don’t seek to minimize risk. They seek to optimize it. They drive and walk and love and play so that they achieve what they desire, but they push themselves a bit at the same time, too, so they continue to develop. Thus, if things are made too safe, people (including children) start to figure out ways to make them dangerous again.165

When untrammeled—and encouraged—we prefer to live on the edge. There, we can still be both confident in our experience and confronting the chaos that helps us develop. We’re hard-wired, for that reason, to enjoy risk (some of us more than others). We feel invigorated and excited when we work to optimize our future performance, while playing in the present. Otherwise we lumber around, sloth-like, unconscious, unformed and careless. Overprotected, we will fail when something dangerous, unexpected and full of opportunity suddenly makes its appearance, as it inevitably will.

The skatestoppers are unattractive. The surround of the nearby sculpture would have to have been badly damaged by diligent board-sliders before it would look as mean as it does now, studded with metal like a pit bull’s collar. The large plant boxes have metal guards placed at irregular intervals across their tops, and this, in addition to the wear caused by the skateboarders, produces a dismal impression of poor design, resentment and badly executed afterthoughts. It gives the area, which was supposed to be beautified by the sculpture and vegetation, a generic industrial/prison/mental institution/work-camp look of the kind that appears when builders and public officials do not like or trust the people they serve.

The sheer harsh ugliness of the solution makes a lie of the reasons for its implementation.

Success and Resentment

If you read the depth psychologists—Freud and Jung, for example, as well as their precursor, Friedrich Nietzsche—you learn that there is a dark side to everything. Freud delved deeply into the latent, implicit content of dreams, which were often aimed, in his opinion, at the expression of some improper wish. Jung believed that every act of social propriety was accompanied by its evil twin, its unconscious shadow. Nietzsche investigated the role played by what he termed ressentiment in motivating what were ostensibly selfless actions—and, often, exhibited all too publicly.166

For that man be delivered from revenge—that is for me the bridge to the highest hope, and a rainbow after long storms. The tarantulas, of course, would have it otherwise. “What justice means to us is precisely that the world be filled with the storms of our revenge”—thus they speak to each other. “We shall wreak vengeange and abuse on all whose equals we are not”—thus do the tarantula-hearts vow. “And ‘will to equality’ shall henceforth be the name for virtue; and against all that has power we want to raise our clamor!” You preachers of equality, the tyrant-mania of impotence clamors thus out of you for equality: your most secret ambitions to be tyrants thus shroud themselves in words of virtue.

The incomparable English essayist George Orwell knew this sort of thing well. In 1937, he wrote The Road to Wigan Pier, which was in part a scathing attack on upper-class British socialists (this, despite being inclined towards socialism himself). In the first half of this book, Orwell portrays the appalling conditions faced by UK miners in the 1930s:167

Several dentists have told me that in industrial districts a person over thirty with any of his or her own teeth is coming to be an abnormality. In Wigan various people gave me their opinion that it is best to get shut of your teeth as early in life as possible. ‘Teeth is just a misery,’ one woman said to me.

A Wigan Pier coal miner had to walk—crawl would be a better word, given the height of the mine shafts—up to three miles, underground, in the dark, banging his head and scraping his back, just to get to his seven-and-a-half-hour shift of backbreaking work. After that, he crawled back. “It is comparable, perhaps, to climbing a smallish mountain before and after your day’s work,” stated Orwell. None of the time spent crawling was paid.

Orwell wrote The Road to Wigan Pier for the Left Book Club, a socialist publishing group that released a select volume every month. After reading the first half of his book, which deals directly with the miners’ personal circumstances, it is impossible not to feel sympathy for the working poor. Only a monster could keep his heart hardened through the accounts of the lives Orwell describes:

It is not long since conditions in the mines were worse than they are now. There are still living a few very old women who in their youth have worked underground, crawling on all fours and dragging tubs of coal. They used to go on doing this even when they were pregnant.

In book’s second half, however, Orwell turned his gaze to a different problem: the comparative unpopularity of socialism in the UK at the time, despite the clear and painful inequity observable everywhere. He concluded that the tweed-wearing, armchair-philosophizing, victim-identifying, pity-and-contempt-dispensing social-reformer types frequently did not like the poor, as they claimed. Instead, they just hated the rich. They disguised their resentment and jealousy with piety, sanctimony and self-righteousness. Things in the unconscious—or on the social justice–dispensing leftist front—haven’t changed much, today. It is because of of Freud, Jung, Nietzsche—and Orwell—that I always wonder, “What, then, do you stand against?” whenever I hear someone say, too loudly, “I stand for this!” The question seems particularly relevant if the same someone is complaining, criticizing, or trying to change someone else’s behaviour.

I believe it was Jung who developed the most surgically wicked of psychoanalytic dicta: if you cannot understand why someone did something, look at the consequences—and infer the motivation. This is a psychological scalpel. It’s not always a suitable instrument. It can cut too deeply, or in the wrong places. It is, perhaps, a last-resort option. Nonetheless, there are times when its application proves enlightening.

If the consequences of placing skatestoppers on plant-boxes and sculpture bases, for example, is unhappy adolescent males and brutalist aesthetic disregard of beauty then, perhaps, that was the aim. When someone claims to be acting from the highest principles, for the good of others, there is no reason to assume that the person’s motives are genuine. People motivated to make things better usually aren’t concerned with changing other people—or, if they are, they take responsibility for making the same changes to themselves (and first). Beneath the production of rules stopping the skateboarders from doing highly skilled, courageous and dangerous things I see the operation of an insidious and profoundly anti-human spirit.

More about Chris

My friend Chris, whom I wrote about earlier, was possessed by such a spirit—to the serious detriment of his mental health. Part of what plagued him was guilt. He attended elementary and junior high school in a number of towns, up in the frigid expanses of the northernmost Alberta prairie, prior to ending up in the Fairview I wrote about earlier. Fights with Native kids were a too-common part of his experience, during those moves. It’s no overstatement to point out that such kids were, on average, rougher than the white kids, or that they were touchier (and they had their reasons). I knew this well from my own experience.

I had a rocky friendship with a Métis kid, Rene Heck,*1 when I was in elementary school. It was rocky because the situation was complex. There was a large cultural divide between Rene and me. His clothes were dirtier. He was rougher in speech and attitude. I had skipped a grade in school, and was, in addition, small for my age. Rene was a big, smart, good-looking kid, and he was tough. We were in grade six together, in a class taught by my father. Rene was caught chewing gum. “Rene,” said my father, “spit that gum out. You look like a cow.” “Ha, ha,” I laughed, under my breath. “Rene the cow.” Rene might have been a cow, but there was nothing wrong with his hearing. “Peterson,” he said, “after school—you’re dead.”

Earlier in the morning, Rene and I had arranged to see a movie that night at the local movie theatre, the Gem. It looked like that was off. In any case, the rest of the day passed, quickly and unpleasantly, as it does when threat and pain lurk. Rene was more than capable of giving me a good pounding. After school, I took off for the bike stands outside the school as fast as I could, but Rene beat me there. We circled around the bikes, him on one side, me on the other. We were characters in a “Keystone Cops” short. As long as I kept circling, he couldn’t catch me, but my strategy couldn’t work forever. I yelled out that I was sorry, but he wasn’t mollified. His pride was hurt, and he wanted me to pay.

I crouched down and hid behind some bikes, keeping an eye on Rene. “Rene,” I yelled, “I’m sorry I called you a cow. Let’s quit fighting.” He started to approach me again. I said, “Rene, I am sorry I said that. Really. And I still want to go to the movie with you.” This wasn’t just a tactic. I meant it. Otherwise what happened next would not have happened. Rene stopped circling. Then he stared at me. Then he broke into tears. Then he ran off. That was Native-white relationships in a nutshell, in our hard little town. We never did go to a movie together.

When my friend Chris got into it with Native kids, he wouldn’t fight back. He didn’t feel that his self-defence was morally justified, so he took his beatings. “We took their land,” he later wrote. “That was wrong. No wonder they’re angry.” Over time, step by step, Chris withdrew from the world. It was partly his guilt. He developed a deep hatred for masculinity and masculine activity. He saw going to school or working or finding a girlfriend as part of the same process that had led to the colonization of North America, the horrible nuclear stalemate of the cold war, and the despoiling of the planet. He had read some books about Buddhism, and felt that negation of his own Being was ethically required, in the light of the current world situation. He came to believe that the same applied to others.

When I was an undergraduate, Chris was, for a while, one of my roommates. One late night we went to a local bar. We walked home, afterward. He started to snap the side-view mirrors off parked cars, one after the other. I said, “Quit that, Chris. What possible good is it going to do to make the people who own these cars miserable?” He told me that they were all part of the frenetic human activity that was ruining everything, and that they deserved whatever they got. I said that taking revenge on people who were just living normal lives was not going to help anything.

Years later, when I was in graduate school in Montreal, Chris showed up, for what was supposed to be a visit. He was aimless, however, and lost. He asked if I could help. He ended up moving in. I was married by then, living with my wife, Tammy, and our year-old daughter, Mikhaila. Chris had also been friends with Tammy back in Fairview (and held out hopes of more than friendship). That complicated the situation even more—but not precisely in the manner you might think. Chris started by hating men, but he ended by hating women. He wanted them, but he had rejected education, and career, and desire. He smoked heavily, and was unemployed. Unsurprisingly, therefore, he was not of much interest to women. That made him bitter. I tried to convince him that the path he had chosen was only going to lead to further ruin. He needed to develop some humility. He needed to get a life.

One evening, it was Chris’s turn to make dinner. When my wife came home, the apartment was filled with smoke. Hamburgers were burning furiously in the frying pan. Chris was on his hands and knees, attempting to repair something that had come loose on the legs of the stove. My wife knew his tricks. She knew he was burning dinner on purpose. He resented having to make it. He resented the feminine role (even though the household duties were split in a reasonable manner; even though he knew that perfectly well). He was fixing the stove to provide a plausible, even creditable excuse for burning the food. When she pointed out what he was doing, he played the victim, but he was deeply and dangerously furious. Part of him, and not the good part, was convinced that he was smarter than anyone else. It was a blow to his pride that she could see through his tricks. It was an ugly situation.

Tammy and I took a walk up towards a local park the next day. We needed to get away from the apartment, although it was thirty-five below—bitterly, frigidly cold, humid and foggy. It was windy. It was hostile to life. Living with Chris was too much, Tammy said. We entered the park. The trees forked their bare branches upward through the damp grey air. A black squirrel, tail hairless from mange, gripped a leafless branch, shivered violently, struggling to hold on against the wind. What was it doing out there in the cold? Squirrels are partial hibernators. They only come out in the winter when it’s warm. Then we saw another, and another, and another, and another, and another. There were squirrels all around us in the park, all partially hairless, tails and bodies alike, all windblown on their branches, all shaking and freezing in the deathly cold. No one else was around. It was impossible. It was inexplicable. It was exactly appropriate. We were on the stage of an absurdist play. It was directed by God. Tammy left soon after with our daughter for a few days elsewhere.

Near Christmas time, that same year, my younger brother and his new wife came out to visit from western Canada. My brother also knew Chris. They all put on their winter clothes in preparation for a walk around downtown Montreal. Chris put on a long dark winter coat. He pulled a black toque, a brimless knitted cap, far down over his head. His coat was black, as were his pants and boots. He was very tall, and thin, and somewhat stooped. “Chris,” I joked. “You look like a serial killer.” Ha bloody ha. The three came back from their walk. Chris was out of sorts. There were strangers in his territory. Another happy couple. It was salt in his wounds.

We had dinner, pleasantly enough. We talked, and ended the evening. But I couldn’t sleep. Something wasn’t right. It was in the air. At four in the morning, I had had enough. I crawled out of bed. I knocked quietly on Chris’s door and went without waiting for an answer into his room. He was awake on the bed, staring at the ceiling, as I knew he would be. I sat down beside him. I knew him very well. I talked him down from his murderous rage. Then I went back to bed, and slept. The next morning my brother pulled me aside. He wanted to speak with me. We sat down. He said, “What the hell was going on last night? I couldn’t sleep at all. Was something wrong?” I told my brother that Chris wasn’t doing so well. I didn’t tell him that he was lucky to be alive—that we all were. The spirit of Cain had visited our house, but we were left unscathed.

Maybe I picked up some change in scent that night, when death hung in the air. Chris had a very bitter odour. He showered frequently, but the towels and the sheets picked up the smell. It was impossible to get them clean. It was the product of a psyche and a body that did not operate harmoniously. A social worker I knew, who also knew Chris, told me of her familiarity with that odour. Everyone at her workplace knew of it, although they only discussed it in hushed tones. They called it the smell of the unemployable.

Soon after this I finished my post-doctoral studies. Tammy and I moved away from Montreal to Boston. We had our second baby. Now and then, Chris and I talked on the phone. He came to visit once. It went well. He had found a job at an auto-parts place. He was trying to make things better. He was OK at that point. But it didn’t last. I didn’t see him in Boston again. Almost ten years later—the night before Chris’s fortieth birthday, as it happened—he called me again. By this time, I had moved my family to Toronto. He had some news. A story he had written was going to be published in a collection put together by a small but legitimate press. He wanted to tell me that. He wrote good short stories. I had read them all. We had discussed them at length. He was a good photographer, too. He had a good, creative eye. The next day, Chris drove his old pickup—the same battered beast from Fairview—into the bush. He ran a hose from the exhaust pipe into the front cab. I can see him there, looking through the cracked windshield, smoking, waiting. They found his body a few weeks later. I called his dad. “My beautiful boy,” he sobbed.

Recently, I was invited to give a TEDx talk at a nearby university. Another professor talked first. He had been invited to speak because of his work—his genuinely fascinating, technical work—with computationally intelligent surfaces (like computer touchscreens, but capable of being placed everywhere). He spoke instead about the threat human beings posed to the survival of the planet. Like Chris—like far too many people—he had become anti-human, to the core. He had not walked as far down that road as my friend, but the same dread spirit animated them both.

He stood in front of a screen displaying an endless slow pan of a blocks-long Chinese high-tech factory. Hundreds of white-suited workers stood like sterile, inhuman robots behind their assembly lines, soundlessly inserting piece A into slot B. He told the audience—filled with bright young people—of the decision he and his wife had made to limit their number of children to one. He told them it was something they should all consider, if they wanted to regard themselves as ethical people. I felt that such a decision was properly considered—but only in his particular case (where less than one might have been even better). The many Chinese students in attendance sat stolidly through his moralizing. They thought, perhaps, of their parents’ escape from the horrors of Mao’s Cultural Revolution and its one-child policy. They thought, perhaps, of the vast improvement in living standard and freedom provided by the very same factories. A couple of them said as much in the question period that followed.

Would have the professor reconsidered his opinions, if he knew where such ideas can lead? I would like to say yes, but I don’t believe it. I think he could have known, but refused to. Worse, perhaps: he knew, but didn’t care—or knew, and was headed there, voluntarily, in any case.