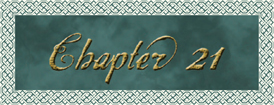

HE APOTHEOSIS of Washington—a 4,664-square-foot fresco that covers the canopy of the Capitol Rotunda—was completed in 1865 by Constantino Brumidi.

HE APOTHEOSIS of Washington—a 4,664-square-foot fresco that covers the canopy of the Capitol Rotunda—was completed in 1865 by Constantino Brumidi.

Known as “The Michelangelo of the Capitol,” Brumidi had laid claim to the Capitol Rotunda in the same way Michelangelo had laid claim to the Sistine Chapel, by painting a fresco on the room’s most lofty canvas—the ceiling. Like Michelangelo, Brumidi had done some of his finest work inside the Vatican. Brumidi, however, immigrated to America in 1852, abandoning God’s largest shrine in favor of a new shrine, the U.S. Capitol, which now glistened with examples of his mastery—from the trompe l’oeil of the Brumidi Corridors to the frieze ceiling of the Vice President’s Room. And yet it was the enormous image hovering above the Capitol Rotunda that most historians considered to be Brumidi’s masterwork.

THE APOTHEOSIS OF WASHINGTON, U.S. CAPITOL ROTUNDA CEILING

21.1: © Photo DC

Robert Langdon gazed up at the massive fresco that covered the ceiling. He usually enjoyed his students’ startled reactions to this fresco’s bizarre imagery, but at the moment he simply felt trapped in a nightmare he had yet to understand.

Director Sato was standing next to him with her hands on her hips, frowning up at the distant ceiling. Langdon sensed she was having the same reaction many had when they first stopped to examine the painting at the core of their nation.

Utter confusion.

You’re not alone, Langdon thought. For most people, The Apotheosis of Washington got stranger and stranger the longer they looked at it. “That’s George Washington on the central panel,” Langdon said, pointing 180 feet upward into the middle of the dome. “As you can see, he’s dressed in regal clothing, attended by thirteen maidens, and ascending on a cloud above mortal man. This is the moment of his apotheosis … his transformation into a god.”

GEORGE WASHINGTON, THE APOTHEOSIS OF WASHINGTON (DETAIL)

21.2: © Rachele Pearce

Sato and Anderson said nothing.

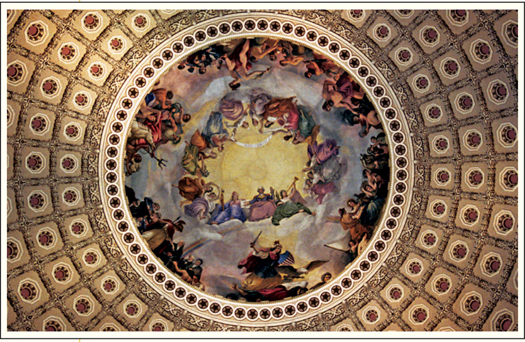

“Nearby,” Langdon continued, “you can see a strange, anachronistic series of figures: ancient gods presenting our forefathers with advanced knowledge. There’s Minerva giving technological inspiration to our nation’s great inventors—Ben Franklin, Robert Fulton, Samuel Morse.” Langdon pointed them out one by one. “And over there is Vulcan helping us build a steam engine. Beside them is Neptune demonstrating how to lay the transatlantic cable. Beside that is Ceres, goddess of grain and root of our word cereal; she’s sitting on the McCormick reaper, the farming breakthrough that enabled this country to become a world leader in food production. The painting quite overtly portrays our forefathers receiving great wisdom from the gods.” He lowered his head, looking at Sato now. “Knowledge is power, and the right knowledge lets man perform miraculous, almost godlike tasks.”

MINERVA, THE APOTHEOSIS OF WASHINGTON (DETAIL)

21.3: © Rachele Pearce

Sato dropped her gaze back down to Langdon and rubbed her neck. “Laying a phone cable is a far cry from being a god.”

“Perhaps to a modern man,” Langdon replied. “But if George Washington knew that we had become a race that possessed the power to speak to one another across oceans, fly at the speed of sound, and set foot on our moon, he would assume that we had become gods, capable of miraculous tasks.” He paused. “In the words of futurist Arthur C. Clarke, ‘Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.’ ”

Sato pursed her lips, apparently deep in thought. She glanced down at the hand, and then followed the direction of the outstretched index finger up into the dome. “Professor, you were told, ‘Peter will point the way.’ Is that correct?”

“Yes, ma’am, but—”

“Chief,” Sato said, turning away from Langdon, “can you get us a closer look at the painting?”

Anderson nodded. “There’s a catwalk around the interior of the dome.”

Langdon looked way, way up to the tiny railing visible just beneath the painting and felt his body go rigid. “There’s no need to go up there.” He had experienced that seldom-visited catwalk once before, as the guest of a U.S. senator and his wife, and he had almost fainted from the dizzying height and perilous walkway.

“No need?” Sato demanded. “Professor, we have a man who believes this room contains a portal that has the potential to make him a god; we have a ceiling fresco that symbolizes the transformation of a man into a god; and we have a hand pointing straight at that painting. It seems everything is urging us upward.”

“Actually,” Anderson interjected, glancing up, “not many people know this, but there is one hexagonal coffer in the dome that actually swings open like a portal, and you can peer down through it and—”

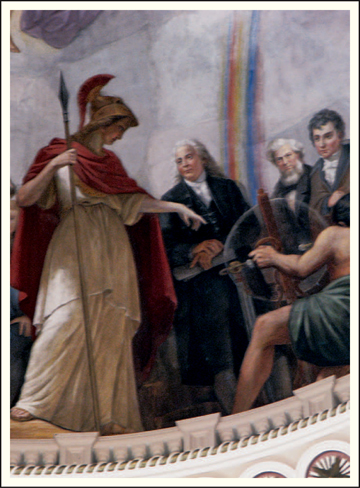

“Wait a second,” Langdon said, “you’re missing the point. The portal this man is looking for is a figurative portal—a gateway that doesn’t exist. When he said, ‘Peter will point the way,’ he was talking in metaphorical terms. This pointing-hand gesture—with its index finger and thumb extended upward—is a well-known symbol of the Ancient Mysteries, and it appears all over the world in ancient art. This same gesture appears in three of Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous encoded masterpieces—The Last Supper, Adoration of the Magi, and Saint John the Baptist. It’s a symbol of man’s mystical connection to God.” As above, so below. The madman’s bizarre choice of words was starting to feel more relevant now.

THE LAST SUPPER, LEONARDO DA VINCI (DETAIL)

21.4: Santa Maria della Grazie, Milan, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library

ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST, LEONARDO DA VINCI

21.5: Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library

“I’ve never seen it before,” Sato said.

Then watch ESPN, Langdon thought, always amused to see professional athletes point skyward in gratitude to God after a touchdown or home run. He wondered how many knew they were continuing a pre-Christian mystical tradition of acknowledging the mystical power above, which, for one brief moment, had transformed them into a god capable of miraculous feats.

“If it’s of any help,” Langdon said, “Peter’s hand is not the first such hand to make an appearance in this Rotunda.”

Sato eyed him like he was insane. “I beg your pardon?”

Langdon motioned to her BlackBerry. “Google ‘George Washington Zeus.’ ”

Sato looked uncertain but started typing. Anderson inched toward her, looking over her shoulder intently.

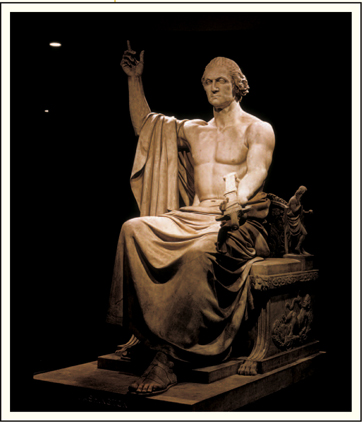

Langdon said, “This Rotunda was once dominated by a massive sculpture of a bare-chested George Washington … depicted as a god. He sat in the same exact pose as Zeus in the Pantheon, bare chest exposed, left hand holding a sword, right hand raised with thumb and finger extended.”

Sato had apparently found an online image, because Anderson was staring at her BlackBerry in shock. “Hold on, that’s George Washington?”

“Yes,” Langdon said. “Depicted as Zeus.”

“Look at his hand,” Anderson said, still peering over Sato’s shoulder. “His right hand is in the same exact position as Mr. Solomon’s.”

GEORGE WASHINGTON SCULPTED AS ZEUS, HORATIO GREENOUGH

21.6: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC/Art Resource, NY

As I said, Langdon thought, Peter’s hand is not the first to make an appearance in this room. When Horatio Greenough’s statue of a naked George Washington was first unveiled in the Rotunda, many joked that Washington must be reaching skyward in a desperate attempt to find some clothes. As American religious ideals changed, however, the joking criticism turned to controversy, and the statue was removed, banished to a shed in the east garden. Currently, it made its home at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, where those who saw it had no reason to suspect that it was one of the last vestigial links to a time when the father of the country had watched over the U.S. Capitol as a god … like Zeus watching over the Pantheon.

Sato began dialing a number on her BlackBerry, apparently seeing this as an opportune moment to check in with her staff. “What have you got?” She listened patiently. “I see …” She glanced directly at Langdon, then at Peter’s hand. “You’re certain?” She listened a moment longer. “Okay, thanks.” She hung up and turned back toward Langdon. “My support staff did some research and confirms the existence of your so-called Hand of the Mysteries, corroborating everything you said: five fingertip markings—the star, the sun, the key, the crown, and the lantern—as well as the fact that this hand served as an ancient invitation to learn secret wisdom.”

“I’m glad,” Langdon said.

“Don’t be,” she replied curtly. “It appears we’re now at a dead end until you share whatever it is you’re still not telling me.”

“Ma’am?”

Sato stepped toward him. “We’ve come full circle, Professor. You’ve told me nothing I could not have learned from my own staff. And so I will ask you once more. Why were you brought here tonight? What makes you so special? What is it that you alone know?”

“We’ve been through this,” Langdon fired back. “I don’t know why this guy thinks I know anything at all!”

Langdon was half tempted to demand how the hell Sato knew that he was in the Capitol tonight, but they’d been through that, too. Sato isn’t talking. “If I knew the next step,” he told her, “I’d tell you. But I don’t. Traditionally, the Hand of the Mysteries is extended by a teacher to a student. And then, shortly afterward, the hand is followed up with a set of instructions … directions to a temple, the name of the master who will teach you—something! But all this guy left for us is five tattoos! Hardly—” Langdon stopped short.

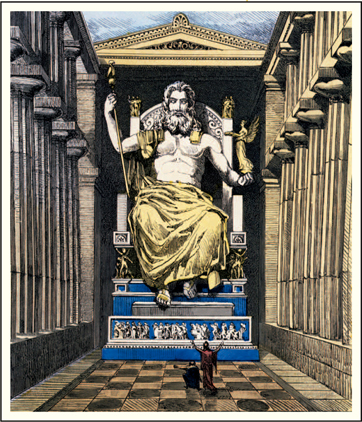

STATUE OF ZEUS BY PHEIDIAS, ENGRAVING, 1866

21.7: Private Collection/ Archives Charmet/The Bridgeman Art Library

Sato eyed him. “What is it?”

Langdon’s eyes shot back to the hand. Five tattoos. He now realized that what he was saying might not be entirely true.

“Professor?” Sato pressed.

Langdon inched toward the gruesome object. Peter will point the way. “Earlier, it crossed my mind that maybe this guy had left an object clenched in Peter’s palm—a map, or a letter, or a set of directions.”

“He didn’t,” Anderson said. “As you can see, those three fingers are not clenched tightly.”

“You’re right,” Langdon said. “But it occurs to me …” He crouched down now, trying to see up under the fingers to the hidden part of Peter’s palm. “Maybe it’s not written on paper.”

“Tattooed?” Anderson said.

Langdon nodded.

“Do you see anything on the palm?” Sato asked.

Langdon crouched lower, trying to peer up under the loosely clenched fingers. “The angle is impossible. I can’t—”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake,” Sato said, moving toward him. “Just open the damned thing!”

Anderson stepped in front of her. “Ma’am! We should really wait for forensics before we touch—”

“I want some answers,” Sato said, pushing past him. She crouched down, edging Langdon away from the hand.

Langdon stood up and watched in disbelief as Sato pulled a pen from her pocket, sliding it carefully under the three clenched fingers. Then, one by one, she pried each finger upward until the hand stood fully open, with its palm visible.

She glanced up at Langdon, and a thin smile spread across her face. “Right again, Professor.”