NOTHER TATTOO.

NOTHER TATTOO.

Langdon crouched anxiously beside Peter’s open palm and examined the seven tiny symbols that had been hidden beneath the lifeless clenched fingers.

“They appear to be numbers,” Langdon said, surprised. “Although I don’t recognize them.”

“The first is a Roman numeral,” Anderson said.

“Actually, I don’t think so,” Langdon corrected. “The Roman numeral I-I-I-X doesn’t exist. It would be written V-I-I.”

“How about the rest of it?” Sato asked.

“I’m not sure. It looks like eight-eight-five in Arabic numbers.”

“Arabic?” Anderson asked. “They look like normal numbers.”

“Our normal numbers are Arabic.” Langdon had become so accustomed to clarifying this point for his students that he’d actually prepared a lecture about the scientific advances made by early Middle Eastern cultures, one of them being our modern numbering system, whose advantages over Roman numerals included “positional notation” and the invention of the number zero. Of course, Langdon always ended this lecture with a reminder that Arab culture had also given mankind the word al-kuhl—the favorite beverage of Harvard freshmen—known as alcohol.

Langdon scrutinized the tattoo, feeling puzzled. “And I’m not even sure about the eight-eight-five. The rectilinear writing looks unusual. Those may not be numbers.”

“Then what are they?” Sato asked.

“I’m not sure. The whole tattoo looks almost … runic.”

“Meaning?” Sato asked.

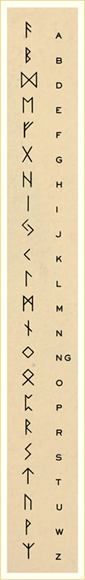

“Runic alphabets are composed solely of straight lines. Their letters are called runes and were often used for carving in stone because curves were too difficult to chisel.”

“If these are runes,” Sato said, “what is their meaning?”

Langdon shook his head. His expertise extended only to the most rudimentary runic alphabet—Futhark—a third-century Teutonic system, and this was not Futhark. “To be honest, I’m not even sure these are runes. You’d need to ask a specialist. There are dozens of different forms—Hälsinge, Manx, the ‘dotted’ Stungnar—”

A SAMPLE RUNIC ALPHABET

“Peter Solomon is a Mason, is he not?”

Langdon did a double take. “Yes, but what does that have to do with this?” He stood up now, towering over the tiny woman.

“You tell me. You just said that runic alphabets are used for stone carvings, and it is my understanding that the original Freemasons were stone craftsmen. I mention this only because when I asked my office to search for a connection between the Hand of the Mysteries and Peter Solomon, their search returned one link in particular.” She paused, as if to emphasize the importance of her finding. “The Masons.”

Langdon exhaled, fighting the impulse to tell Sato the same thing he constantly told his students: “Google” is not a synonym for “research.” In these days of massive, worldwide keyword searches, it seemed everything was linked to everything. The world was becoming one big entangled web of information that was getting denser every day.

Langdon maintained a patient tone. “I’m not surprised the Masons appeared in your staff’s search. Masons are a very obvious link between Peter Solomon and any number of esoteric topics.”

“Yes,” Sato said, “which is another reason I have been surprised this evening that you have not yet mentioned the Masons. After all, you’ve been talking about secret wisdom protected by an enlightened few. That sounds very Masonic, does it not?”

“It does … and it also sounds very Rosicrucian, Kabbalistic, Alumbradian, and any number of other esoteric groups.”

“But Peter Solomon is a Mason—a very powerful Mason, at that. It seems the Masons would come to mind if we were talking about secrets. Heaven knows the Masons love their secrets.”

Langdon could hear the distrust in her voice, and he wanted no part of it. “If you want to know anything about the Masons, you would be far better served to ask a Mason.”

“Actually,” Sato said, “I’d prefer to ask someone I can trust.”

Langdon found the comment both ignorant and offensive. “For the record, ma’am, the entire Masonic philosophy is built on honesty and integrity. Masons are among the most trustworthy men you could ever hope to meet.”

“I have seen persuasive evidence to the contrary.”

Langdon was liking Director Sato less and less with each passing moment. He had spent years writing about the Masons’ rich tradition of metaphorical iconography and symbols, and knew that Masons had always been one of the most unfairly maligned and misunderstood organizations in the world. Regularly accused of everything from devil worship to plotting a one-world government, the Masons also had a policy of never responding to their critics, which made them an easy target.

ANTI-MASONIC ARTWORK: DEVIL WORSHIP FROM “THE FREEMASONS,” EUGEN LENNHOFF, 1932

23.1: Private Collection/Ken Welsh/The Bridgeman Art Library

“Regardless,” Sato said, her tone biting, “we are again at an impasse, Mr. Langdon. It seems to me there is either something you are missing … or something you are not telling me. The man we’re dealing with said that Peter Solomon chose you specifically.” She leveled a cold stare at Langdon. “I think it’s time we move this conversation to CIA headquarters. Maybe we’ll have more luck there.”

Sato’s threat barely registered with Langdon. She had just said something that had lodged in his mind. Peter Solomon chose you. The comment, combined with the mention of Masons, had hit Langdon strangely. He looked down at the Masonic ring on Peter’s finger. The ring was one of Peter’s most prized possessions—a Solomon family heirloom that bore the symbol of the double-headed phoenix—the ultimate mystical icon of Masonic wisdom. The gold glinted in the light, sparking an unexpected memory.

Langdon gasped, recalling the eerie whisper of Peter’s captor: It really hasn’t dawned on you yet, has it? Why you were chosen?

Now, in one terrifying moment, Langdon’s thoughts snapped into focus and the fog lifted.

All at once, Langdon’s purpose here was crystal clear.

Ten miles away, driving south on Suitland Parkway, Mal’akh heard a distinctive vibration on the seat beside him. It was Peter Solomon’s iPhone, which had proven a powerful tool today. The visual caller ID now displayed the image of an attractive middle-aged woman with long black hair.

INCOMING CALL—KATHERINE SOLOMON

Mal’akh smiled, ignoring the call. Destiny pulls me closer.

He had lured Katherine Solomon to his home this afternoon for one reason only—to determine if she had information that could assist him … perhaps a family secret that might help Mal’akh locate what he sought. Clearly, however, Katherine’s brother had told her nothing of what he had been guarding all these years.

Even so, Mal’akh had learned something else from Katherine. Something that has earned her a few extra hours of life today. Katherine had confirmed for him that all of her research was in one location, safely locked inside her lab.

I must destroy it.

Katherine’s research was poised to open a new door of understanding, and once the door was opened even a crack, others would follow. It would just be a matter of time before everything changed. I cannot let that happen. The world must stay as it is … adrift in ignorant darkness.

The iPhone beeped, indicating Katherine had left a voice mail. Mal’akh retrieved it.

“Peter, it’s me again.” Katherine’s voice sounded concerned. “Where are you? I’m still thinking about my conversation with Dr. Abaddon … and I’m worried. Is everything okay? Please call me. I’m at the lab.”

The voice mail ended.

Mal’akh smiled. Katherine should worry less about her brother, and more about herself. He turned off Suitland Parkway onto Silver Hill Road. Less than a mile later, in the darkness, he spotted the faint outline of the SMSC nestled in the trees off the highway to his right. The entire complex was surrounded by a high razor-wire fence.

A secure building? Mal’akh chuckled to himself. I know someone who will open the door for me.

HE REVELATION crashed over Langdon like a wave.

HE REVELATION crashed over Langdon like a wave.

I know why I am here.

Standing in the center of the Rotunda, Langdon felt a powerful urge to turn and run away … from Peter’s hand, from the shining gold ring, from the suspicious eyes of Sato and Anderson. Instead, he stood dead still, clinging more tightly to the leather daybag that hung on his shoulder. I’ve got to get out of here.

His jaw clenched as his memory began replaying the scene from that cold morning, years ago in Cambridge. It was six A.M. and Langdon was entering his classroom as he always did following his ritual morning laps in the Harvard Pool. The familiar smells of chalk dust and steam heat greeted him as he crossed the threshold. He took two steps toward his desk but stopped short.

A figure was waiting there for him—an elegant gentleman with an aquiline face and regal gray eyes.

“Peter?” Langdon stared in shock.

Peter Solomon’s smile flashed white in the dimly lit room. “Good morning, Robert. Surprised to see me?” His voice was soft, and yet there was power there.

Langdon hurried over and warmly shook his friend’s hand. “What in the world is a Yale blue blood doing on the Crimson campus before dawn?”

“Covert mission behind enemy lines,” Solomon said, laughing. He motioned to Langdon’s trim waistline. “Laps are paying off. You’re in good shape.”

“Just trying to make you feel old,” Langdon said, toying with him. “It’s great to see you, Peter. What’s up?”

“Short business trip,” the man replied, glancing around the deserted classroom. “I’m sorry to drop in on you like this, Robert, but I have only a few minutes. There’s something I needed to ask you … in person. A favor.”

That’s a first. Langdon wondered what a simple college professor could possibly do for the man who had everything. “Anything at all,” he replied, pleased for any opportunity to do something for someone who had given him so much, especially when Peter’s life of good fortune had also been marred by so much tragedy.

Solomon lowered his voice. “I was hoping you would consider looking after something for me.”

Langdon rolled his eyes. “Not Hercules, I hope.” Langdon had once agreed to take care of Solomon’s hundred-fifty-pound mastiff, Hercules, during Solomon’s travels. While at Langdon’s home, the dog apparently had become homesick for his favorite leather chew toy and had located a worthy substitute in Langdon’s study—an original vellum, hand-calligraphed, illuminated Bible from the 1600s. Somehow “bad dog” didn’t quite seem adequate.

“You know, I’m still searching for a replacement,” Solomon said, smiling sheepishly.

“Forget it. I’m glad Hercules got a taste of religion.”

Solomon chuckled but seemed distracted. “Robert, the reason I came to see you is I’d like you to keep an eye on something that is quite valuable to me. I inherited it a while back, but I’m no longer comfortable leaving it in my home or in my office.”

Langdon immediately felt uncomfortable. Anything “quite valuable” in Peter Solomon’s world had to be worth an absolute fortune. “How about a safe-deposit box?” Doesn’t your family have stock in half the banks in America?

“That would involve paperwork and bank employees; I’d prefer a trusted friend. And I know you can keep secrets.” Solomon reached in his pocket and pulled out a small package, handing it to Langdon.

Considering the dramatic preamble, Langdon had expected something more impressive. The package was a small cube-shaped box, about three inches square, wrapped in faded brown packing paper and tied with twine. From the package’s heavy weight and size, it felt like its contents must be rock or metal. This is it? Langdon turned the box in his hands, now noticing the twine had been carefully secured on one side with an embossed wax seal, like an ancient edict. The seal bore a double-headed phoenix with the number 33 emblazoned on its chest—the traditional symbol of the highest degree of Freemasonry.

“Really, Peter,” Langdon said, a lopsided grin creeping across his face. “You’re the Worshipful Master of a Masonic lodge, not the pope. Sealing packages with your ring?”

Solomon glanced down at his gold ring and gave a chuckle. “I didn’t seal this package, Robert. My great-grandfather did. Almost a century ago.”

Langdon’s head snapped up. “What?!”

Solomon held up his ring finger. “This Masonic ring was his. After that, it was my grandfather’s, then my father’s … and eventually mine.”

Langdon held up the package. “Your great-grandfather wrapped this a century ago and nobody has opened it?”

“That’s right.”

“But … why not?”

Solomon smiled. “Because it’s not time.”

Langdon stared. “Time for what?”

“Robert, I know this will sound odd, but the less you know, the better. Just put this package somewhere safe, and please tell no one I gave it to you.”

Langdon searched his mentor’s eyes for a glint of playfulness. Solomon had a propensity for dramatics, and Langdon wondered if he wasn’t being played a bit here. “Peter, are you sure this isn’t just a clever ploy to make me think I’ve been entrusted with some kind of ancient Masonic secret so I’ll be curious and decide to join?”

“The Masons do not recruit, Robert, you know that. Besides, you’ve already told me you’d prefer not to join.”

This was true. Langdon had great respect for Masonic philosophy and symbolism, and yet he had decided never to be initiated; the order’s vows of secrecy would prevent him from discussing Freemasonry with his students. It had been for this same reason that Socrates had refused to formally participate in the Eleusinian Mysteries.

As Langdon now regarded the mysterious little box and its Masonic seal, he could not help but ask the obvious question. “Why not entrust this to one of your Masonic brothers?”

“Let’s just say I have an instinct it would be safer stored outside the brotherhood. And please don’t let the size of this package fool you. If what my father told me is correct, then it contains something of substantial power.” He paused. “A talisman, of sorts.”

Did he say a talisman? By definition, a talisman was an object with magical powers. Traditionally, talismans were used for bringing luck, warding off evil spirits, or aiding in ancient rituals. “Peter, you do realize that talismans went out of vogue in the Middle Ages, right?”

Peter laid a patient hand on Langdon’s shoulder. “I know how this sounds, Robert. I’ve known you a long time, and your skepticism is one of your greatest strengths as an academic. It is also your greatest weakness. I know you well enough to know you’re not a man I can ask to believe … only to trust. So now I am asking you to trust me when I tell you this talisman is powerful. I was told it can imbue its possessor with the ability to bring order from chaos.”

Langdon could only stare. The idea of “order from chaos” was one of the great Masonic axioms. Ordo ab chao. Even so, the claim that a talisman could impart any power at all was absurd, much less the power to bring order from chaos.

“This talisman,” Solomon continued, “would be dangerous in the wrong hands, and unfortunately, I have reason to believe powerful people want to steal it from me.” His eyes were as serious as Langdon could ever recall. “I would like you to keep it safe for me for a while. Can you do that?”

That night, Langdon sat alone at his kitchen table with the package and tried to imagine what could possibly be inside. In the end, he simply chalked it up to Peter’s eccentricity and locked the package in his library’s wall safe, eventually forgetting all about it.

That was … until this morning.

The phone call from the man with the southern accent.

“Oh, Professor, I almost forgot!” the assistant had said after giving Langdon the specifics of his travel arrangements to D.C. “There is one more thing Mr. Solomon requested.”

“Yes?” Langdon replied, his mind already moving to the lecture he had just agreed to give.

“Mr. Solomon left a note here for you.” The man began reading awkwardly, as if trying to decipher Peter’s penmanship. “ ‘Please ask Robert … to bring … the small, sealed package I gave him many years ago.’ ” The man paused. “Does this make any sense to you?”

Langdon felt surprised as he recalled the small box that had been sitting in his wall safe all this time. “Actually, yes. I know what Peter means.”

“And you can bring it?”

“Of course. Tell Peter I’ll bring it.”

“Wonderful.” The assistant sounded relieved. “Enjoy your speech tonight. Safe travels.”

Before leaving home, Langdon had dutifully retrieved the wrapped package from the back of his safe and placed it in his shoulder bag.

Now he was standing in the U.S. Capitol, feeling certain of only one thing. Peter Solomon would be horrified to know how badly Langdon had failed him.