NSIDE THE Statuary Hall, Robert Langdon clutched his cell phone to his ear and paced in a tight circle. “Who the hell are you?”

NSIDE THE Statuary Hall, Robert Langdon clutched his cell phone to his ear and paced in a tight circle. “Who the hell are you?”

The man’s reply was a silky calm whisper. “Do not be alarmed, Professor. You have been summoned here for a reason.”

“Summoned?” Langdon felt like a caged animal. “Try kidnapped!”

“Hardly.” The man’s voice was eerily serene. “If I wanted to harm you, you would be dead in your Town Car right now.” He let the words hang for a moment. “My intentions are purely noble, I assure you. I would simply like to offer you an invitation.”

No thanks. Ever since his experiences in Europe over the last several years, Langdon’s unwanted celebrity had made him a magnet for nutcases, and this one had just crossed a very serious line. “Look, I don’t know what the hell is going on here, but I’m hanging up—”

“Unwise,” said the man. “Your window of opportunity is very small if you want to save Peter Solomon’s soul.”

Langdon drew a sharp breath. “What did you say?”

“I’m sure you heard me.”

The way this man had uttered Peter’s name had stopped Langdon cold. “What do you know about Peter?”

“At this point, I know his deepest secrets. Mr. Solomon is my guest, and I can be a persuasive host.”

This can’t be happening. “You don’t have Peter.”

“I answered his private cell phone. That should give you pause.”

“I’m calling the police.”

“No need,” the man said. “The authorities will join you momentarily.”

What is this lunatic talking about? Langdon’s tone hardened. “If you have Peter, put him on the phone right now.”

“That’s impossible. Mr. Solomon is trapped in an unfortunate place.” The man paused. “He is in the Araf.”

“Where?” Langdon realized he was clutching his phone so tightly his fingers were going numb.

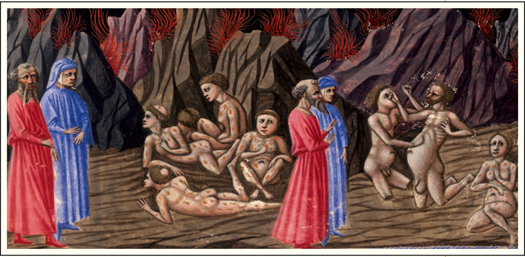

“The Araf? Hamistagan? That place to which Dante devoted the canticle immediately following his legendary Inferno?”

A SCENE FROM DANTE’S INFERNO, EARLY 15TH CENTURY, MADE FOR ALPHONSO V, KING OF ARAGON

9.1: British Library, London/HIP/Art Resource, NY

The man’s religious and literary references solidified Langdon’s suspicion that he was dealing with a madman. The second canticle. Langdon knew it well; nobody escaped Phillips Exeter Academy without reading Dante. “You’re saying you think Peter Solomon is … in purgatory?”

“A crude word you Christians use, but yes, Mr. Solomon is in the in-between.”

The man’s words hung in Langdon’s ear. “Are you saying Peter is … dead?”

“Not exactly, no.”

“Not exactly?!” Langdon yelled, his voice echoing sharply in the hall. A family of tourists looked over at him. He turned away and lowered his voice. “Death is usually an all-or-nothing thing!”

“You surprise me, Professor. I expected you to have a better understanding of the mysteries of life and death. There is a world in between—a world in which Peter Solomon is hovering at the moment. He can either return to your world, or he can move on to the next … depending on your actions right now.”

Langdon tried to process this. “What do you want from me?”

“It’s simple. You have been given access to something quite ancient. And tonight, you will share it with me.”

“I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

“No? You pretend not to understand the ancient secrets that have been entrusted to you?”

Langdon felt a sudden sinking sensation, now guessing what this was probably about. Ancient secrets. He had not uttered a word to anyone about his experiences in Paris several years earlier, but Grail fanatics had followed the media coverage closely, some connecting the dots and believing Langdon was now privy to secret information regarding the Holy Grail—perhaps even its location.

“Look,” Langdon said, “if this is about the Holy Grail, I can assure you I know nothing more than—”

“Don’t insult my intelligence, Mr. Langdon,” the man snapped. “I have no interest in anything so frivolous as the Holy Grail or mankind’s pathetic debate over whose version of history is correct. Circular arguments over the semantics of faith hold no interest for me. Those are questions answered only through death.”

The stark words left Langdon confused. “Then what the hell is this about?”

The man paused for several seconds. “As you may know, there exists within this city an ancient portal.”

An ancient portal?

“And tonight, Professor, you will unlock it for me. You should be honored I contacted you—this is the invitation of your lifetime. You alone have been chosen.”

And you have lost your mind. “I’m sorry, but you’ve chosen poorly,” Langdon said. “I don’t know anything about any ancient portal.”

“You don’t understand, Professor. It was not I who chose you … it was Peter Solomon.”

“What?” Langdon replied, his voice barely a whisper.

“Mr. Solomon told me how to find the portal, and he confessed to me that only one man on earth could unlock it. And he said that man is you.”

“If Peter said that, he was mistaken … or lying.”

“I think not. He was in a fragile state when he confessed that fact, and I am inclined to believe him.”

Langdon felt a stab of anger. “I’m warning you, if you hurt Peter in any—”

“It’s far too late for that,“ the man said in an amused tone. “I’ve already taken what I need from Peter Solomon. But for his sake, I suggest you provide what I need from you. Time is of the essence … for both of you. I suggest you find the portal and unlock it. Peter will point the way.”

Peter? “I thought you said Peter was in ‘purgatory.’ ”

“As above, so below,” the man said.

Langdon felt a deepening chill. This strange response was an ancient Hermetic adage that proclaimed a belief in the physical connection between heaven and earth. As above, so below. Langdon eyed the vast room and wondered how everything had veered so suddenly out of control tonight. “Look, I don’t know how to find any ancient portal. I’m calling the police.”

“It really hasn’t dawned on you yet, has it? Why you were chosen?”

“No,” Langdon said.

“It will,” he replied, chuckling. “Any moment now.”

Then the line went dead.

Langdon stood rigid for several terrifying moments, trying to process what had just happened.

Suddenly, in the distance, he heard an unexpected sound.

It was coming from the Rotunda.

Someone was screaming.

OBERT LANGDON had entered the Capitol Rotunda many times in his life, but never at a full sprint. As he ran through the north entrance, he spotted a group of tourists clustered in the center of the room. A small boy was screaming, and his parents were trying to console him. Others were crowding around, and several security guards were doing their best to restore order.

OBERT LANGDON had entered the Capitol Rotunda many times in his life, but never at a full sprint. As he ran through the north entrance, he spotted a group of tourists clustered in the center of the room. A small boy was screaming, and his parents were trying to console him. Others were crowding around, and several security guards were doing their best to restore order.

“He pulled it out of his sling,” someone said frantically, “and just left it there!”

As Langdon drew nearer, he got his first glimpse of what was causing all the commotion. Admittedly, the object on the Capitol floor was odd, but its presence hardly warranted screaming.

The device on the floor was one Langdon had seen many times. The Harvard art department had dozens of these—life-size plastic models used by sculptors and painters to help them render the human body’s most complex feature, which, surprisingly, was not the human face but rather the human hand. Someone left a mannequin hand in the Rotunda?

Mannequin hands, or handequins as some called them, had articulated fingers enabling an artist to pose the hand in whatever position he wanted, which for sophomoric college students was often with the middle finger extended straight up in the air. This handequin, however, had been positioned with its index finger and thumb pointing up toward the ceiling.

“HANDEQUIN” ART MODEL

10.1: © Robert Bull

As Langdon drew nearer, though, he realized this handequin was unusual. Its plastic surface was not smooth like most. Instead, the surface was mottled and slightly wrinkled, and appeared almost …

Like real skin.

Langdon stopped abruptly.

The severed wrist appeared to have been skewered onto a spiked wooden base so that it would stand up. A wave of nausea rushed over him. Langdon inched closer, unable to breathe, seeing now that the tips of the index finger and thumb had been decorated with tiny tattoos. The tattoos, however, were not what held Langdon’s attention. His gaze moved instantly to the familiar golden ring on the fourth finger.

No.

Langdon recoiled. His world began to spin as he realized he was looking at the severed right hand of Peter Solomon.