PART I

Paris September 1891

CHAPTER 1

PARIS

WEDNESDAY 16TH SEPTEMBER 1891

Léonie Vernier stood on the steps of the Palais Garnier, clutching her chatelaine bag and tapping her foot impatiently.

Where is he?

Dusk cloaked the Place de l’Opéra in a silky blue light.

Léonie frowned. It was quite maddening. For almost one hour she had waited for her brother at the agreed rendezvous , beneath the impassive bronze gaze of the statues that graced the roof of the opera house. She had endured impertinent looks. She had watched the fiacres come and go, private carriages with their hoods up, public conveyances open to the elements, four-wheelers, gigs, all disembarking their passengers. A sea of black silk top hats and fine evening gowns from the showrooms of Maison Léoty and Charles Worth. It was an elegant first-night audience, a sophisticated crowd come to see and be seen.

But no Anatole.

Once, Léonie thought she spied him. A gentleman of her brother’s bearing and proportions, tall and broad, and with the same measured step. From a distance, she even imagined his shining brown eyes and fine black moustache and raised her hand to wave. But then the man turned and she saw it was not he.

Léonie returned her gaze to the Avenue de l’Opéra. It stretched diagonally all the way down to the Palais du Louvre, a remnant of fragile monarchy when a nervous French king sought a safe and direct route to his evening’s entertainment . The lanterns twinkled in the dusk, and squares of warm light spilled out through the lighted windows of the cafés and bars. The gas jets spat and spluttered.

Around her, the air was filled with the sounds of a city at dusk, as day gave way to night. Entre chien et loup. The clink of harness and wheels on the busy streets. The song of distant birds in the trees in the Boulevard des Capucines. The raucous cries of hawkers and ostlers, the sweeter tones of the girls selling artificial flowers on the steps of the Opéra, the high-pitched shouts of the boys who, for a sou, would blacken and shine a gentleman’s shoes.

Another omnibus passed between Léonie and the magnificent façade of the Palais Garnier on its way to the Boulevard Haussmann, the conductor whistling on the upper deck as he punched tickets. An old soldier with a Tonquin medal pinned to his breast stumbled back and forth, singing an intoxicated army song. Léonie even saw a clown with a whitened face under his black domino felt cap, in a costume covered with gold spangles.

How could he leave me waiting?

The bells began to ring out for evensong, the plangent tones echoing across the cobbles. From Saint-Gervais or another church nearby?

She gave a half-shrug. Her eyes flashed with frustration, then exhilaration.

Léonie could delay no longer. If she wished to hear Monsieur Wagner’s Lohengrin, then she must take her courage in both hands and go in alone.

Could she?

Although without an escort, by good fortune she was in possession of her own ticket.

But dare she?

She considered. It was the Parisian premiere. Why should she be deprived of such an experience because of Anatole’s poor timekeeping?

Inside the opera house, the glass chandeliers glittered magnificently. It was all light and elegance, an occasion not to be missed.

Léonie made her decision. She ran up the steps, through the glass doors, and joined the crowd.

The warning bell was ringing. Two minutes only until curtain up.

In a flash of petticoat and silk stockings, Léonie dashed across the marble expanse of the Grand Foyer, attracting approbation and admiration in equal measure. At the age of seventeen, Léonie was on the verge of becoming a great beauty, no longer a child, but retaining yet flashes of the girl she had been. She was fortunate to be possessed of the fashionable good features and nostalgic colouring held in high regard by Monsieur Moreau and his Pre-Raphaelite friends.

But her looks were misleading. Léonie was determined rather than obedient, bold rather than modest, a girl of contemporary passions, not a demure medieval damsel. Indeed, Anatole teased that while she appeared the very portrait of Rossetti’s La Damoiselle Élue, she was in point of fact her mirror image. Her doppelgänger, her but not her. Of the four elements, Léonie was fire not water, earth not air .

Now, her alabaster cheeks were flushed. Thick ringlets of copper hair had come loose from her combs and tumbled down over bare shoulders. Her dazzling green eyes, framed by long auburn lashes, flashed with anger, and boldness.

He gave his word that he would not be late.

Clutching her evening bag in one hand, as if it was a shield, the skirts of her green silk satin gown in the other, Léonie hurtled across the marble floors, paying no heed to the disapproving stares of matrons and widows. The faux pearls and silver beads on the fringe of her dress clipped against the marble treads of the steps as she rushed through the rose marble columns, the gilded statues and the friezes, and towards the sweeping Grand Escalier. Confined in her corset, her breath came ragged and her heart pumped like a metronome set too fast.

Still Léonie did not check her pace. Ahead, she could see the flunkeys moving to secure the doors into the Grande Salle. With a final spurt of energy, she propelled herself forward to the entrance.

‘Voilà,’ she said, thrusting her ticket at the usher. ‘Mon frère va arriver . . .’

He stepped aside and permitted her to pass.

After the noisy and echoing marble caverns of the Grand Foyer, the auditorium was particularly quiet. Filled with hushed murmurings, words of salutation, enquiries after health and family, all half swallowed up by the thick carpets and row upon row of red velvet seats.

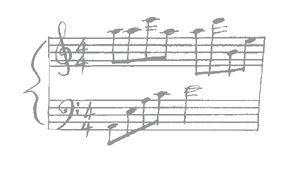

The familiar flights of woodwind and brass, scales and arpeggios and fragments of the opera, increasingly loud, issued up from the orchestra pit like trails of autumn smoke.

I did it.

Léonie composed herself and smoothed her gown. A new purchase, delivered from La Samaritaine this afternoon, it was still stiff from lack of wear. She pulled her long green gloves up above her elbows, so that no more than a sliver of bare skin could be seen, then walked down through the stalls towards the stage.

Their seats were in the front row, two of the best in the house, courtesy of Anatole’s composer friend and their neighbour, Achille Debussy. To left and right, as she passed, were lines of black top hats and feathered headdresses and fluttering sequined fans. Choleric faces of red and purple, heavily powdered dowagers with set white hair. She returned each and every look with a cordial smile, a slight tilt of the head.

There is a strange intensity in the atmosphere.

Léonie’s gaze sharpened. The further she went into the Grande Salle, the clearer it became that something was amiss. There was a watchfulness in the faces, something simmering only just beneath the surface, an expectation of trouble to come.

She felt a prickling at the base of her neck. The audience was on its guard. She saw it in the darting glances and mistrustful expressions on every other face.

Don’t be absurd.

Léonie had a faint memory of a newspaper article read aloud at the supper table by Anatole about protests against the presentation in Paris of works of Prussian artists. But this was the Palais Garnier, not some secluded alleyway in Clichy or Montmartre.

What could happen at the Opéra?

Léonie picked her way through the forest of knees and gowns along the row and with a sense of relief sat down in her seat. She took a moment to compose herself and then glanced at her neighbours. To her left were a heavily jewelled matron and her elderly husband, his watery eyes all but obscured beneath bushy white brows. Mottled hands rested, one on top of the other, on the head of a silver-topped cane with an inscription band around the neck. To her right, with Anatole’s empty seat making a barrier between them like a country ditch, sat four scowling and bearded men of middle years with sour expressions, each set of hands resting upon undistinguished boxwood walking sticks. There was something rather unnerving about the way they sat in silence facing front, an expression of intense concentration upon their faces.

It passed through Léonie’s mind that it was singular that they should all be wearing leather gloves, and how uncomfortably hot they must be. Then one turned his head and stared at her. Léonie blushed and, fixing her eyes front, admired instead the magnificent trompe l’oeil curtains, which hung in folds of crimson and gold from the top of the proscenium arch to the wooden surface of the stage.

Maybe he is not late? What if some ill has befallen him?

Léonie shook her head at this new and unwelcome thought.

She pulled out her fan from her bag and flicked it open with a snap. However much she might wish to make excuses for her brother, it was more likely to be a matter of poor timekeeping.

As so often these days.

Indeed, since the dismal events in the Cimetière de Montmartre, Anatole had been even less reliable. Léonie frowned at how, yet again, the memory slipped back into her mind. The day haunted her. She relived it endlessly.

In March she had hoped that it was all over and done with, but his behaviour was still erratic. Often he disappeared for days on end, returning at odd hours of the night, avoiding many of his friends and acquaintances and throwing himself instead into his work.

But tonight he promised he would not be late.

The chef d’orchestre walked on to the rostrum, scattering Léonie’s thoughts. A round of applause filled the expectant auditorium, like a volley of gunfire, violent and sudden and intense. Léonie clapped with vigour and enthusiasm, all the stronger for her anxious state. The quartet of gentlemen beside her did not move. Their hands remained motionless, perched on their cheap, ugly walking sticks. She threw them a look, thinking them discourteous and boorish and wondering why they would even bother to come if they were determined not to appreciate the music. And she wished, although it irritated her to acknowledge such nerves, that she was not sitting so very close to them.

The conductor bowed deeply, then turned to face the stage.

The applause faded. Silence fell over the Grande Salle. He tapped his baton upon his wooden stand. The blue jets of gaslight in the auditorium spluttered and flickered, then dimmed. The atmosphere became charged with promise. Every eye was upon the chef d’orchestre. The men of the orchestra straightened their backs and lifted their bows or raised instruments to their lips.

The chef lifted his baton. Léonie caught her breath as the opening chords of Monsieur Wagner’s Lohengrin filled the palatial spaces of the Palais Garnier.

The seat beside her remained empty.