CHAPTER 93

‘Bonjorn, Madomaisèla,’ came a voice from the shadows. At first Léonie thought her ears were deceiving her.

He stepped out of the gloom to greet her. ‘I have been absent for too long.’

She leapt forward, her hands outstretched. ‘Monsieur Baillard,’ she cried. ‘You are most welcome, most welcome!’

He smiled down at Louis-Anatole, hopping from foot to foot beside him.

‘This young man has looked after me very well,’ he said. ‘He has been amusing me by playing the piano.’

Without waiting for further invitation, Louis-Anatole ran back across the black and red tiles, threw himself upon the piano stool and began to play.

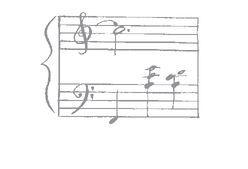

‘Listen to me, Tante Léonie,’ he called out. ‘I found this in the piano stool. I have been learning it on my own.’

A haunting melody in the key of A minor, lilting and gentle, his small hands struggling not to split the chords. Music, at last, heard. Played, and played so beautifully, by Anatole’s son.

Sepulchre 1891.

Léonie felt tears brim in her eyes. She felt Audric Baillard’s hand take hers, his skin so dry. They stood listening, until the last chord faded away.

Louis-Anatole dropped his hands into his lap, took a deep breath, as if listening to the reverberations in the almost silence, then turned to face them with a look of pride on his face.

‘There,’ he said. ‘I have practised. For you, Tante Léonie.’

‘You have a great talent, Sénher,’ said Monsieur Baillard, applauding.

Louis-Anatole beamed with pleasure. ‘If I cannot be a soldier when I am a man, then I shall travel to America and be a famous pianist.’

‘Noble occupations, both,’ laughed Baillard. Then the smile slipped from his face. ‘But now, my accomplished young friend, there are matters your tante and I must discuss. If you will excuse us?’

‘But I—’

‘It will not be for long, petit,’ said Léonie firmly. ‘We will be sure to call for you when we are finished.’

Louis-Anatole sighed, then shrugged and, with a grin, ran off towards the kitchens calling for Marieta.

As soon as he had gone, Monsieur Baillard and Léonie went quickly into the drawing room. Under his precise and careful questioning, Léonie explained everything that had happened since he had quit Rennes-les-Bains in January, the tragic, the surreal, the mystifying, including her suspicions that Victor Constant might have returned.

‘I did write of our troubles,’ she said, unable to keep the reproach from her voice, ‘but I had no way of knowing if you had received any of my communications.’

‘Some I did, others I suspect went astray,’ he said in a sombre tone. ‘The tragic news of Madama Isolde’s death I learned only when I returned this afternoon. I was sorry to hear it.’

Léonie looked at him, seeing how tired and frail he looked. ‘It was a release. She had been unhappy for some time,’ she said quietly. She clasped her hands together. ‘Tell me, where have you been? I have missed your company greatly.’

He pressed the tips of his long, slim fingers together, as if in prayer.

‘If it had not been a matter of great personal importance to me,’ he said softly, ‘I would not have left you. But I had received word that a person . . . a person for whom I have been waiting for many, many years had returned. But …’ He paused, and in the silence, Léonie heard the raw pain behind the simple words. ‘But it was not she.’

Léonie was momentarily diverted. She had heard him talk only once before with such affection, but had received the impression that the girl of whom he spoke with such tenderness was some years dead.

‘I am not certain I understand you, Monsieur Baillard,’ she said carefully.

‘No,’ he said softly. Then a look of determination came over his features. ‘Had I known, I would not have left Rennes-les-Bains.’ He sighed. ‘But I took advantage of my journey to prepare some refuge for you and Louis-Anatole.’

Léonie’s green eyes flared wide in surprise.

‘But I only came to that decision a week ago,’ she objected. ‘Less. You have been gone for ten months. How could you have …’

He gave a slow smile. ‘I feared, long ago, that it would be necessary.’

‘But how—’

He raised his hand. ‘Your suspicions are correct, Madama Léonie. Victor Constant is indeed in the vicinity of the Domaine de la Cade.’

Léonie fell still. ‘If you have evidence, we must inform the authorities. They have refused to take my concerns seriously thus far.’

‘I have no evidence, only assured suspicions. But, I have no doubt, Constant is here for a purpose. You must leave tonight. My house in the mountains is prepared and waiting for you. I will give directions to Pascal.’ He paused. ‘He and Marieta – his wife, now, I believe – will travel with you?’

Léonie nodded. ‘I have confided my intentions to them.’

‘You may remain in Los Seres for as long as you wish. Certainly until it is safe to return.’

‘Thank you, thank you.’

With tears in her eyes, Léonie looked around the room. ‘I shall be sorry to leave this house,’ she said softly. ‘For my mother and for Isolde, it was an unhappy place. But for me, despite the sorrows that have been contained here, it has been a home.’

She stopped. ‘There is one thing I must confess to you, Monsieur Baillard.’

His gaze sharpened.

‘Six years ago, I gave you my word that I would not return to the sepulchre,’ she said quietly. ‘And I kept my promise. But as for the cards, I must tell you that, after I took my leave of you that day in Rennes-les-Bains . . . before the duel and Anatole …’

‘I remember,’ he said softly.

‘I took it upon myself to take the path home through the woods to see if I might find the cachette for myself. I wanted only to see if I might find the Tarot cards.’

She looked at Monsieur Baillard, expecting to see disappointment, even reproof, on his face. To her astonishment, he was smiling.

‘And you came upon the place.’

It was a statement, not a question.

‘I did. But I give you my word,’ Léonie said, rushing on, ‘that although I looked upon the cards, I returned them to their hiding place.’ She paused. ‘But I would not now leave them here, within the grounds. He might discover them, and then …’

As she was speaking, Audric Baillard reached into the large white pocket of his suit. He took out a square of black silk, a familiar parcel of material, and opened it up. The image of La Force was visible on the top.

‘You have them!’ Léonie exclaimed, taking a step towards him. Then she stopped. ‘You knew I had been there?’

‘Obligingly, you left your gloves as a memento. Do you not remember?’

Léonie flushed to the roots of her copper hair.

He folded the black silk. ‘I went because, like you, I do not believe these cards should be in the possession of such a man as Victor Constant. And . . .’ He paused. ‘I believe we might have need of them.’

‘You warned me against using the power of the cards,’ she objected.

‘Unless or until there was no other choice,’ he said quietly. ‘I fear that hour is at hand.’

Léonie felt her heart start to race. ‘Let us leave now, right away.’ She was suddenly horribly aware of her heavy winter petticoats and her stockings scratching against her skin. The mother-of-pearl combs in her hair, a gift from Isolde, seemed to dig into her scalp like sharp teeth. ‘Let us go. Now.’

Without warning, she found herself remembering their happy first weeks at the Domaine de la Cade – she and Anatole and Isolde – before tragedy struck. How in that long-ago autumn of 1891 it was the darkness she had feared most, impenetrable and absolute, after the bright lights of Paris.

Il était une fois. Once upon a time.

She was another girl then, innocent, untouched by darkness or grief. Tears blurred her vision and she shut her eyes.

The sound of running feet across the hall set her memories to flight. She leapt up and turned in the direction of the noise, at the precise moment the drawing room door burst open and Pascal stumbled into the room.

‘Madama Léonie, Sénher Baillard,’ he shouted. ‘There are . . . men. They have already forced their way through the gates!’

Léonie ran to the window. On the distant horizon, she could see a line of flaming torches, gold and ochre against the black night sky.

Then, closer at hand, she heard the sound of glass breaking.