CODA

Three Years Later

SUNDAY 31ST OCTOBER 2010

‘Ladies and gentlemen, good evening. My name is Mark and it’s my great honour to welcome Ms Meredith Martin to our bookstore tonight.’

There was a burst of enthusiastic, if sparse, applause, then a hush descended over the tiny independent bookstore. Hal, sitting in the front row, smiled encouragement at her. Standing at the back, her arms folded, was her publisher, who gave the thumbs-up sign.

‘As many of you know,’ the manager continued, ‘Ms Martin is the author of the acclaimed biography of the French composer Claude Debussy, which came out last year to rave reviews. However, what you may not know …’

Mark was an old friend, and Meredith had a horrible feeling he was going to start way back, taking the audience all the way through elementary school, through high school to university, before he even got on to the subject of the book.

She let her mind wander, running down familiar paths. She thought about everything that had happened to bring her to this point. Three years of research, evidence, checking and double-checking, trying to fit together the pieces of Léonie’s history at the same time as struggling to finish and deliver her biography of Debussy on time.

Meredith never did figure out if Lilly Debussy had visited Rennes-les-Bains, but the two stories collided pretty early on in a more exciting way. She discovered that the Verniers and the Debussys had been neighbours in the rue de Berlin in Paris. And when Meredith visited Debussy’s grave in the Cimitière de Passy in the 16th arrondissement, where Manet and Morisot, Fauré and André Messager were also buried, she had found, hidden in a corner of the cemetery beneath the trees, the tomb of Marguerite Vernier.

The following year, back in Paris with Hal, Meredith paid a visit to lay flowers on the grave.

As soon as she’d delivered the biography in the spring of 2008, Meredith had concentrated full time on researching the Domaine de la Cade and how her family had emigrated from France to America.

She started with Léonie. The more Meredith read about Rennes-les-Bains and the theories surrounding Abbé Saunière and Rennes-le-Château, the more convinced she was that Hal’s opinion that it was all part of a smokescreen to draw attention away from what had happened at the Domaine de la Cade was right. She was inclined to think that the three corpses discovered in the 1950s in the garden of Abbé Saunière’s home in Rennes-le-Château were connected to the events of 31st October 1897 in the Domaine de la Cade.

Meredith suspected that one of the bodies was that of Victor Constant, the man who murdered Anatole and Marguerite Vernier. Records showed Constant had fled to Spain and been treated in several clinics for third-stage syphilis, but that he had returned to France in the fall of 1897. The second might have been Constant’s manservant, who was known to have been among the mob that attacked the house. His body had never been found. The third was harder to account for. A twisted spine, abnormally long arms, a person of no more than four feet in height.

The other event that caught Meredith’s attention was the murder of Curé Antoine Gélis of Coustaussa, some time during the same night in October 1897. Gélis was a recluse. On the surface, his death seemed unconnected with the events at the Domaine de la Cade, apart from the coincidence of the date. He had been attacked first with his own fire tongs, then an axe lying in the grate of the old presbytery. The Courrier d’Aude reported there were fourteen wounds to his head and multiple skull fractures.

It was a particularly savage and apparently motiveless murder. The killers were never found. All the local newspapers of the time carried the story and the details were much the same. Having killed the old man, the murderers laid out the body, crossing the old man’s hands across his chest. The house had been searched and a strongbox forced open, but it was said by a niece who looked after him to be empty anyway. Nothing appeared to have been taken.

When Meredith researched a little deeper, she discovered two details buried deep in one of the newspaper reports. First, that on the afternoon of Hallowe’en, a girl matching the description of Léonie Vernier visited the presbytery in Coustaussa. A handwritten note was recovered. Second, that a Tarot card had been left pushed between the fingers of the dead man’s left hand.

Card XV: Le Diable.

When Meredith had read that, recalling what had happened in the ruins of the sepulchre, she thought she understood. The devil, through his servant Asmodeus, had taken his own.

As for who had placed Léonie’s sewing box and the original cards in their hiding place beneath the winterbourne, that remained unresolved. Meredith’s heart imagined Louis-Anatole creeping back into the Domaine de la Cade under cover of night and replacing the cards where they belonged in memory of his aunt. Her head told her it was more likely to have been a man called Audric Baillard, whose role in the story she’d not yet figured out to her own satisfaction.

The genealogical information was more straightforward to pin down. With the assistance of the same lady in the town hall in Rennes-les-Bains, who turned out to be both resourceful and extremely efficient, during the summer of 2008 and early fall, Meredith had put together Louis-Anatole’s history. The son of Anatole and Isolde, he had grown up in the care of Audric Baillard in a small village in the Sabarthès mountains called Los Seres. After Léonie’s death, Louis-Anatole had never returned to the Domaine de la Cade and the estate had been allowed to go to ruin. Meredith assumed Louis-Anatole’s guardian was the father, maybe even grandfather, of the Audric S. Baillard who had written Diables et Esprits Maléfiques et Phantômes de la Montagne.

Louis-Anatole Vernier, together with a family servant, Pascal Barthes, had enlisted in the French army in 1914 and seen active service. Pascal was much decorated, but did not survive the war. Louis-Anatole did and, when peace was declared in 1918, he made his way to America, officially signing over the abandoned Domaine de la Cade to his Bousquet relations. To start with, he paid his way playing piano on the steamboats and in vaudeville. Although Meredith couldn’t prove it, she liked to think he might have at least crossed paths with another vaudeville performer, Paul Foster Case.

Louis-Anatole settled outside Milwaukee, in what was now Mitchell Park. It had been pretty easy to uncover the next chapter of the story. He fell in love with a married woman, a Lillian Matthews, who became pregnant and had a daughter, Louisa. Soon after, the affair ended and Lillian and Louis-Anatole appeared to have lost touch. There was no evidence of contact between father and daughter that Meredith could find, although she hoped Louis-Anatole might have followed his daughter’s progress from a distance.

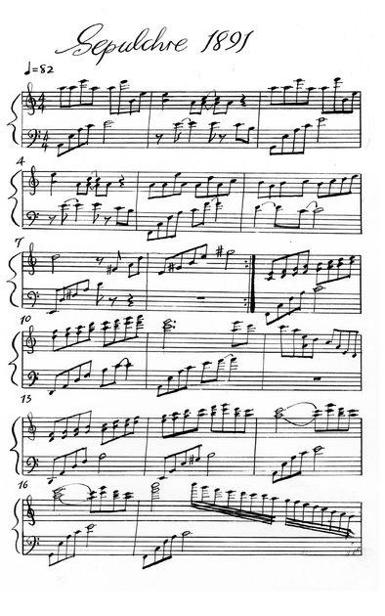

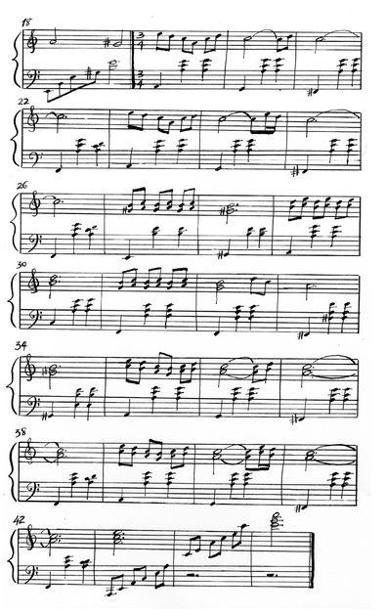

Louisa inherited her father’s musical talent. She became a professional pianist, in the concert halls of 1930s’ America rather than on the steamboats of the Mississippi. After her debut concert, at a small venue in Milwaukee, she found a package waiting for her at the stage door. It contained a single photograph of a young man in uniform and a piece of piano music: Sepulchre 1891.

On the eve of World War II, Louisa became engaged to a fellow musician, a violinist whom she’d met on the concert circuit. Jack Martin was highly strung and volatile, even before his experiences in a Burmese prisoner-of-war camp ruined him. He returned to America, addicted to drugs, suffering hallucinations and nightmares. He and Louisa had a daughter, Jeanette, but it was clearly a tough situation and when Jack disappeared from the scene in the 1950s, Meredith imagined Louisa had not been sorry.

Three years of painstaking research, and she’d made it right up to date. Jeanette had inherited the beauty, the talent, the character of her grandfather, Louis-Anatole, and her mother, Louisa, but also the fragility, the vulnerability of her French great-grandmother Isolde and her father, Jack.

Meredith looked down at the back cover of the book, resting in her nervous lap. A reproduction of the photograph of Léonie, Anatole and Isolde, taken in the square in Rennes-les-Bains in 1891. Her family.

Mark, the store manager, was still talking. Hal caught her eye, and mimed zippering his mouth shut.

Meredith grinned. Hal had moved to America in October 2008, the best birthday present Meredith could have had. The legal side of things down in Rennes-les-Bains had been complicated. Probate had taken a while and there had been problems with ascertaining exactly why Julian Lawrence had died. Not a stroke, not a heart attack. There were no visible signs of any trauma whatsoever, apart from some unexplained scarring on the palms of his hands. His heart had just stopped beating.

Had he survived, it was unlikely he would have faced charges for either the murder of his brother or the attempted murder of Shelagh O’Donnell. The circumstantial evidence in both cases was persuasive, but the police were reluctant to reopen the inquest into Seymour’s death in the circumstances. Shelagh had not seen her attacker and there were no witnesses.

There was, however, clear evidence of fraud and that Julian Lawrence had been skimming the profits and borrowing against it for years to fund his obsession. Several valuable Visigoth artefacts, all illegally obtained, were recovered. In his safe were charts showing his detailed excavations of the grounds and notebook after notebook of scribblings about a particular deck of Tarot cards. When Meredith was questioned, in November 2007, she admitted she had a replica copy of the same deck, but that the originals were believed to have been destroyed in the fire of 1897.

Hal had sold the Domaine de la Cade in March 2008. There was no money in the business, only debts. He had settled his ghosts. He was ready to move on. But he had stayed in touch with Shelagh O’Donnell, who now lived in Quillan, and she told them that an English couple, with two teenage children, had taken over and had successfully transformed the business into one of the leading family hotels in the Midi.

‘So, ladies and gentlemen, please put your hands together for Ms Meredith Martin.’

There was an explosion of riotous clapping, not least, Meredith suspected, because Mark had finally finished talking.

She took a deep breath, composed herself, and stood up.

‘Thank you for that generous introduction, Mark,’ she said, ‘and it’s great to be here. The genesis of this book, as some of you know, comes from a trip I made while I was working on my biography of Debussy. My research took me to a delightful town in the Pyrenees called Rennes-les-Bains, and, from there, into an investigation of my own family background. This memoir is my attempt to lay the ghosts of the past to rest.’ She paused. ‘The heroine of the book, if you like, is a woman called Léonie Vernier. Without her, I wouldn’t be here today.’ She smiled. ‘But the book is dedicated to Mary, my mother. Like Léonie, she’s one amazing lady.’

Meredith saw Hal hand Mary, who was sitting between him and Bill in the front row, a tissue.

‘It was Mary who introduced music into my life. It was she who encouraged me to keep asking questions and to never close my mind to any possibility. It was she who taught me to always stick with it, however hard things got. Most important,’ she grinned, lightening the tone a little, ‘and especially appropriate tonight, I guess, it was Mary who showed me how to make the best pumpkin Hallowe’en lanterns ever!’

The gathering of family and friends laughed.

Meredith waited, now excited as well as nervous, until silence fell over the room once more. She lifted the book and began to read.

This story begins in a city of bones. In the alleyways of the dead. In the silent boulevards and promenades and impasses of the Cimetière de Montmartre in Paris, a place inhabited by tombs and stone angels and the loitering ghosts of those forgotten before they are even cold in their graves.

As her words floated out over the audience, becoming part of the mass of stories to be told that Hallowe’en night, the comfortable sounds of the old building were Meredith’s accompaniment. Chairs creaking on the wooden floorboards, the spluttering of the old water pipes in the roof, the blare of horns from cars in the street outside, the coffee percolator wheezing in the corner. From the bar next door, the strains of a piano coming through the walls. Black and white notes winding through the skirting, the floorboards, the hidden spaces between floor and ceiling.

Meredith slowed down as she came to the end of her reading.

For in truth, this story begins not with the absence of bones in a Parisian graveyard, but with the deck of cards.

With the Vernier Tarot.

There was a moment of silence, and then the applause began.

Meredith realised she’d been half holding her breath, and exhaled with relief. As she looked out at her friends, her family, her colleagues, for a fraction of a second, there in the shifting of the light, she imagined she saw a girl with long copper hair and bright green eyes, standing at the back of the room, smiling.

Meredith smiled back. But when she looked again, there was no one there.

She thought of all the ghosts that touched her life. Marguerite Vernier in the Cimitière de Passy. Of the cemetery in Milwaukee, close to the point where the three rivers met, where her great-grandfather Louis-Anatole Vernier – soldier of France, citizen of America – had been laid to rest. Of Louisa Martin, pianist, her ashes scattered to the winds. Her birth mother, buried on the shores where the sun set over Lake Michigan. But most of all, she thought of Léonie, sleeping peacefully in the ground of the Domaine de la Cade.

Air, water, fire, earth.

‘Thank you,’ Meredith said, as the applause died down. ‘And thank you all very much for coming.’