CHAPTER 19

COUIZA SUNDAY 20TH SEPTEMBER

Léonie had enjoyed their three-day journey through France. As soon as the Express had cleared the dismal Parisian banlieue, Anatole had recovered his good spirits and kept her amused with stories, playing hands of cards, discussing how they would spend their time in the mountains.

At a little after six o’clock on Friday evening, they had disembarked in Marseille. The following day, they continued along the coast to Carcassonne and passed an uncomfortable night in a hotel with no hot water and surly staff. Léonie had woken with a headache this morning and, owing to the difficulty of finding a fiacre on a Sunday morning, they had nearly missed their connection.

However, as soon as the train cleared the outskirts of the town, Léonie’s mood improved. Now, her guidebook lay discarded on the seat, beside a volume of short stories. The living, breathing landscape of the Midi began to work its charm.

The track followed the line of the curving river south, through the silver valley of the Aude towards the Pyrenees. At first, the rails ran alongside the road. The land was flat and unoccupied. But soon she saw rows of vines to left and right, and the occasional field of sunflowers still in bloom, bright and yellow, their heads bowed to the east.

She glimpsed a small village – no more than a handful of houses – perched on a picturesque distant hill. Then another, the red-tiled houses clustered around the dominating spire of the church. Near at hand, on the outskirts of the railside towns, were pink hibiscus, bougainvillea, poignant syringas, lavender bushes and wild poppies. The green prickly helmets of chestnuts hung on the laden branches of the trees. In the distance, gold and polished copper silhouettes, the only hint that autumn was waiting in the wings.

All along the line, peasants were working in the fields, their starched blue smocks stiff and shining as if varnished, decorated with embroidered patterns on collars and cuffs. The women wore wide flat straw hats to keep off the blistering sun. The men bore expressions of resignation upon their leathery faces, turned away from the relentless wind, working so late a harvest.

The train halted for a quarter of an hour at a substantial town called Limoux. After that, the countryside became steeper, rockier, less forgiving as the plains gave way to the garrigue of the Hautes Corbières. The train rattled precariously on, perched on thin tracks above the river, until, rounding a curve, the blue-white Pyrenees suddenly appeared in the distance, shimmering in a heat haze.

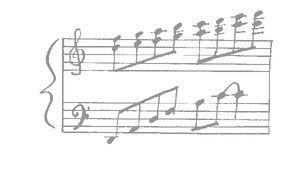

Léonie caught her breath. The mountains seemed to rise up out of the very land, like a mighty wall, connecting earth to heaven. Magnificent, unchanging. In the face of such natural splendour, the manmade constructions of Paris seemed as nothing. The controversies about Monsieur Eiffel’s celebrated metal tower, Baron Haussmann’s grand boulevards, even Monsieur Garnier’s opera house, each paled into insignificance. This was a landscape built on an altogether different scale – earth, air, fire and water. The four elements were laid out in plain view, like keys on a piano.

The train rattled and wheezed, slowing considerably, lunging forwards in jagged bursts. Léonie pushed down the glass and felt the air of the Midi upon her cheeks. Wooded hills, green and brown and crimson, rose abruptly in the shadow of grey granite cliffs. Lulled by the swaying motion of the train and the singing of the wheels upon the metal tracks, she found her eyelids flickering shut.

She was jolted awake by the squeal of the brakes.

Her eyes flew open, and for an instant she forgot where she was. Then she glanced down at the guidebook on her lap, and across to Anatole, and remembered. Not Paris, but in a rattling railway carriage in the Midi.

The train was slowing.

Léonie peered drowsily out of the grimy window. It was hard to make out the lettering on the painted wooden board on the platform. Then she heard the stationmaster, in a heavy southern accent, announce:

‘Couiza-Montazels. Dix minutes d’arrêt.’

She sat forward with a jolt and tapped her brother on the knee.

‘Anatole, nous sommes là. Lève-toi.’

Already she could hear doors opening and falling back against the painted green side of the train with a heavy slap, like a desultory round of applause at the Concerts Lamoureux.

‘Anatole,’ she repeated, certain he must be feigning sleep. ‘C’est l’heure. We have arrived at Couiza.’

She leaned out.

Even this late in the season, and despite it being Sunday, there was a line of porters leaning on high-backed wooden trolleys. Most had their caps set back on their heads and waistcoats open, shirtsleeves rolled up to the elbow.

She raised her arm. ‘Porteur, s’il vous plaît,’ she called.

One leapt forward, clearly thinking how well a couple of sous would sit in his pocket. Léonie withdrew to gather up her belongings.

Without warning, the door was pulled open. ‘Allow me, Mademoiselle.’

A man was standing on the platform looking up into the carriage.

‘No, really, we can manage . . .’ she began to say, but he cast his eyes over the compartment, taking in Anatole’s sleeping figure and the luggage still upon the rack, and without invitation stepped up into the carriage.

‘I insist.’

Léonie took an instant dislike to him. His starched high collar, double-breasted waistcoat and top hat marked him a gentleman, and yet there was something not quite comme il faut about him. His gaze was too bold, too impertinent.

‘Thank you, but there is no need,’ she said. She identified the smell of plum brandy on his breath. ‘I am more than . . .’

But without waiting for permission, he was already lifting the first of their valises and boxes down from the wooden rack. Léonie noticed him glance at the initials inscribed in the leather as he placed Anatole’s portmanteau on the dirty floor.

Thoroughly frustrated by her brother’s inactivity, she shook him roughly by the arm.

‘Anatole, voilà Couiza. Wake up!’

At last, to her relief, he showed signs of stirring. His eyelids flickered, and he stared lazily around him, as if surprised to find himself in a railway carriage at all. Then he caught sight of her, and smiled.

‘Must have dozed off,’ he said, smoothing his long white fingers over his black oiled hair. ‘Desolé.’

Léonie winced as the man dropped Anatole’s personal trunk with a thud on the platform. Then he reached back inside for her lacquered workbox.

‘Take care,’ she said sharply. ‘It is precious.’

The man ran his eyes over her, then over the two gold initials on the top: L.V.

‘But of course. Do not concern yourself.’

Anatole stood up. In an instant, the compartment seemed very much smaller. He glanced at himself in the looking glass below the luggage rack, tipped the collars of his shirt, adjusted his waistcoat and shot his cuffs. Then he bent down and swept up his hat, gloves and cane in one easy motion.

‘Shall we?’ he said casually, offering Léonie his hand.

Only then did he seem to notice that their belongings had been set down from the carriage. He looked at their companion.

‘My thanks, M’sieur. We are most grateful.’

‘Not at all. The pleasure was mine, M’sieur . . .’

‘Vernier. Anatole Vernier. And this is my sister, Léonie.’

‘Raymond Denarnaud, at your service.’ He tipped his hat. ‘Are you putting up in Couiza? If so, I would be delighted to . . .’

The whistle blew once more.

‘En voiture! Passengers for Quillan and Espéraza, en voiture!’

‘We should step away,’ said Léonie.

‘Not in Couiza itself,’ Anatole replied to the man, almost shouting to make himself heard over the roar of the furnace. ‘But close by. Rennes-les-Bains.’

Denarnaud beamed. ‘My home town.’

‘Excellent. We are staying at the Domaine de la Cade? Do you know it?’

Léonie stared at Anatole in astonishment. Having pressed upon her the need for discretion, here he was, only three days out of Paris, publishing their business to a complete stranger without a second thought.

‘Domaine de la Cade,’ Denarnaud replied carefully. ‘Yes, I know of it.’

The engine let out an explosion of steam and clatter. Léonie stepped nervously back and Denarnaud climbed aboard.

‘Again, I must thank you for your courtesy,’ Anatole repeated.

Denarnaud leaned out. The two men exchanged cards, then shook hands as the steam swamped the platform.

Anatole stood back from the edge. ‘Seemed a nice enough fellow.’

Léonie’s eyes flashed with temper. ‘You insisted we should keep our plans private,’ she objected, ‘and yet—’

Anatole cut in. ‘Just being friendly.’

The station clock on the tower began to strike the hour.

‘It seems that we are still, after all, in France,’ said Anatole, then glanced at her. ‘Is something the matter? Is it something I have done? Or not done?’

Léonie sighed. ‘I am cross and I am hot. It was dull having no one to talk to. And you left me quite at the mercies of that disagreeable man.’

‘Oh, Denarnaud wasn’t so bad,’ he objected, squeezing her hand. ‘But I ask your forgiveness anyway for the heinous crime of falling asleep!’

Léonie pulled a face.

‘Come, petite. You will feel more yourself when we have had something to eat and drink.’