CHAPTER 6

The building in the rue de Berlin was quiet.

Léonie let herself into the apartment with a latchkey. An oil lamp had been left burning to light her way. Léonie dropped the key into the china bowl that stood beside the silver post salver, empty of letters or calling cards. Pushing her mother’s stole off the cushion, she sank down on a hall chair. She slipped off her stained slippers and silk stockings, massaging her sore toes and thinking of Anatole’s evasive-ness. If there was no shame attached to his actions, then why would he not tell her why he had been late to the opera?

Léonie glanced along the passageway and saw that her mother’s door was closed. For once, she was disappointed. Often she found Marguerite’s company frustrating, her topics of conversation limited and predictable. But tonight she would have been grateful for a little late-night company.

She took up the lamp and walked into the drawing room. A large and generous room, it occupied the entire front of the house, overlooking the rue de Berlin itself. The three sets of windows were closed, but the curtains of yellow chintz that hung ceiling to floor had been left open.

She placed the lamp upon the table, then looked down on the deserted street. She realised she was chilled to the bone. She thought of Anatole, somewhere in the city, and hoped he was safe.

At last, thoughts of what could have been started to creep up on her. The high spirits that had supported her through the long evening drained away, leaving her frightened and fearful. She felt as if every limb, every muscle, every sense was overtaken by the memory of what she had witnessed.

Blood and cracked bones and hate.

Léonie closed her eyes, but still each separate incident flooded back, distinct, as if caught in the click of the shutter of a box camera. The stench as the homemade bombs of excrement and rotting food burst. The frozen eyes of the man as the knife plunged into his chest, that single paralysing moment between life and death.

There was a green woollen shawl hanging over the back of the chaise longue. She wrapped it around her shoulders, turned down the gas lamp and curled up in her favourite armchair, her legs tucked beneath her.

Suddenly, from the floor beneath, the sound of music began to filter up through the floorboards. Léonie smiled. Achille at his piano again. She looked to the clock on the mantelshelf.

Past midnight.

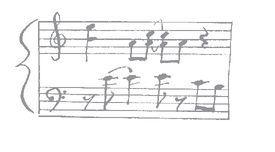

Léonie welcomed the knowledge that she was not the only one awake in the rue de Berlin. There was something soothing about Achille’s presence. She burrowed deeper into the folds of the chair, recognising the piece. La Damoiselle Élue, a composition Anatole often claimed Debussy had written with Léonie in mind. She knew the assertion to be untrue. Achille had told her that the libretto was a prose setting of a poem by Rossetti, which in its turn had been inspired by Monsieur Poe’s The Raven. But false or not, she held the piece close to her heart, and its ethereal chords precisely suited her midnight spirits.

Without warning, another memory swooped down upon her. The morning of the funeral. Then, as now, Achille hammering endlessly on the piano, black notes and white seeping up through the floorboards until Léonie thought she would be driven mad with his playing. The single palm leaf floating in the glass bowl. The sickly aroma of ritual and death that insinuated itself into every corner of the apartment, the burning of incense and candles to mask the cloying sweetness of the corpse in the closed casket.

You are confusing what was with what is.

Then, most mornings, he had disappeared from the apartment before light had given shape back to the world. Most evenings he returned home long after the household had retired. Once, he had been absent for a week without explanation. When Léonie finally mustered the courage to ask him where he had been, he told her only not to concern herself. She supposed he spent his nights at the rouge et noir tables. She knew, too, from the gossip of the servants, that he was being subjected to vociferous and anonymous denunciations in the columns of the newspapers.

The physical toll upon him was obvious. His cheeks grew hollow and his skin transparent. His brown eyes were dulled, permanently bloodshot, and his lips withered and parched. Léonie would do anything to prevent such a deterioration again.

Only when the leaves were returning to the trees in the Boulevard Malesherbes, and when the paths of the Parc Monceau were filled once more with pink and white and lilac blooms, did the attacks upon his good name suddenly cease. From then, his spirits improved and his health recovered. The older brother she knew and loved was restored to her. Since then, there had been no more disappearances, no more evasions, no more half-truths.

Until this evening.

Léonie realised her cheeks were wet. She wiped away the tears with cold fingers, then wrapped the shawl tighter around her.

This is September, not March.

But Léonie remained sick at heart. She knew he had lied to her. So she kept vigil at the window, allowing Achille’s music below to lull her into a half-sleep, whilst all the time listening for the sound of Anatole’s latchkey in the door.

CHAPTER 7

THURSDAY 17TH SEPTEMBER

Leaving the lady sleeping, Anatole crept from the tiny rented room. Careful not to disturb the other lodgers in the boarding house, he walked slowly down the narrow and dusty wooden stairs in stockinged feet. A gas jet burned on each landing, as he descended one flight, then another and another, until he was in the passageway that gave on to the street.

It was not quite dawn, yet Paris was waking. In the distance, Anatole could hear the sounds of delivery carts. Wooden traps over the cobbles delivering milk and freshly baked bread to the cafés and bars of the Faubourg Montmartre.

He stopped to put on his shoes, then set off. The rue Feydeau was deserted and there was no sound except the clip of his heels on the pavement. Deep in thought, Anatole walked quickly, to the junction with the rue Saint-Marc, intending to cut through the arcade of the Passage des Panoramas. He saw no one, heard no one.

His thoughts were rattling around in his head. Would their plan succeed? Could he get out of Paris unobserved and without raising suspicion? For all the fighting talk of the past hours, Anatole entertained doubts. He knew that his conduct over the coming hours, days, would determine their success or failure. Already Léonie was suspicious and since her support would be critical to the success of the endeavour, he cursed the sequence of events that had delayed his arrival at the opera house, then the extraordinary ill fortune that had decreed that the abonnés should have chosen that very night to stage their most bloody and violent protest to date.

He took a deep breath, feeling the crisp September dawn seeping into his lungs, mixed with the steam and smoke and soot of the city. The guilt he had felt at having failed Léonie had been forgotten in the blessed moments while he held his lover in his arms. Now it returned, like a sharp pain in his chest.

He determined he would make it up to her.

The hand of time was on his back, pushing him home-wards. He walked faster, wrapped in thought, delight at the night just past, the memory of his lover imprinted upon his mind and body, the fragrance of skin on his fingers, the texture of her hair. He was weary with the endless secrecy and obfuscation. As soon as they were away from Paris, there would be no more need for intrigue, to invent imaginary visits to the rouge et noir tables or opium dens or houses of ill repute to cover his true whereabouts.

That he had been under attack from the newspapers and unable to defend his own reputation, was a state of affairs that sat uneasily with him. He suspected Constant to have had a hand in it. The blackening of his name affected the situation of both his mother and his sister. All he could hope was that when the matter was out in the open, there would be time enough to repair his standing.

As he turned the corner, a spiteful gust of autumn wind blew at his heels. He pulled his jacket tight around him and regretted the lack of a neck scarf. He crossed the rue Saint-Marc, still wrapped in his thoughts – thinking of the days, the weeks to come, not the present within which he walked.

At first he did not hear the sound of footsteps behind him. Two sets of feet, walking fast, getting closer. His mind sharpened. He glanced down at his evening clothes, realising he looked an easy target. Unarmed, unaccompanied and possibly with winnings from a night at the tables in his pockets.

Anatole walked faster. The footsteps, too, quickened.

Certain now he was being marked, he darted right into the Passage des Panoramas, thinking that if he could cut through to the Boulevard Montmartre, where the cafés would be opening their doors and there was likely to be early morning traffic, milk deliveries, carts, he would be safe.

The few remaining gas lamps burned with a cold blue light as he passed along the narrow row of glass-fronted shops selling stamps and ex-voto trinkets, the furniture-maker displaying an ancient cabinet with dilapidated gilding, the various antiques dealers and sellers of objets d’art.

The men followed.

Anatole felt a spike of fear. His hand went to his pocket, looking for something with which to defend himself, but finding nothing that would serve as a weapon.

He walked faster, resisting the impulse to start running. Better to keep his head up. Pretend all was well. Trust that he would make it through to the other side where there were witnesses before they had the chance to strike.

But behind him now, the sound of running. A flash of movement reflected in the window of Stern’s the engraver, a refracting of the light, and Anatole spun round, in time to ward off a fist coming down upon his head. He took a hit above his left eye, but deflected the worst of it, and managed to land a punch. His attacker wore a flat woollen cap with a black handkerchief obscuring most of his face. He grunted, but at the same time Anatole felt his arms pinned from behind, leaving him exposed. The first blow, to his stomach, knocked the wind out of him, then a fist smashed into his face, left, right, like a boxer in the ring, in a volley of blows that sent his head cracking from side to side and pain ricocheting through him.

Anatole could feel blood trickling from his eyelid, but he managed to twist around slightly to avoid the worst of the hits. The man holding him was also wearing a neckscarf across his face, but his head was uncovered and his hard scalp covered in angry red blisters. Anatole drew up his knee and sent his foot smashing back into the man’s shin. For an instant the hold upon him was loosened, just long enough for Anatole to grab at the open collar of the man’s shirt and, getting purchase, send him staggering against the sharp-edged pillars in the doorway.

Anatole launched himself forward, using the weight of his body to try to get past, but the first man caught him a glancing jab to the side of his head. He half stumbled to his knees, swinging out as he fell and catching the man hard in the ribs, but inflicting little damage.

Anatole felt the man’s fists, clenched together, come down on the back of his neck. The force of the blow sent him staggering forward, then he stumbled and dropped to the ground. A vicious kick from steel-toed boots to the back of his legs had him sprawling forward on the ground. He threw his hands over his head and pulled his knees up to his chin, in a futile attempt to protect himself from the worst of the assault. As one blow, then another followed to his ribs, his kidneys, his arms – he realised for the first time that the beating might not stop.

‘Hey!’

At the end of the passageway, in the gloom, Anatole thought he saw a light.

‘Hey! You! What’s going on?’

For a moment, time stood still. Anatole felt the hot breath of one of the assailants whispering in his ear.

‘Une leçon.’

Then the sensation of hands crawling over his battered body, fingers pushing into the pocket of his waistcoat, a sharp tug, and his father’s fob watch being torn from its clip.

Finally Anatole found his voice.

‘Over here! Here!’

With a final kick to his ribs, causing Anatole’s body to jack-knife in pain, the two attackers left, running in the opposite direction from the inconstant light of the nightwatchman’s lamp.

‘Over here,’ Anatole cried again.

He heard the shuffling feet coming towards him, then the clink of glass and metal on the ground and the old nightwatchman was peering down at him.

‘Monsieur, qu’est-ce qui s’est passé ici?’

Anatole pulled himself up into a sitting position, allowing the old man to help him.

‘I’m all right,’ he said, trying to catch his breath. He put his hand up to his eye and brought his fingers away red.

‘You’ve taken quite a beating.’

‘It’s nothing,’ he insisted. ‘A cut.’

‘Monsieur, you were robbed?’

Anatole didn’t immediately answer. He took a deep breath, then reached his hand up for the nightwatchman to help him to his feet. Pain shot across his back and down his legs. He took a moment to get his balance, then straightened up. He examined his hands, turning them over. His knuckles were cracked and bleeding and his palms were red with blood from the cut above his eye. He could feel a gash on his ankle where the skin was open, rubbing against the material of his trousers.

Anatole took a moment more to compose himself, then he straightened his clothes.

‘Did they take much, sir?’

He patted himself down and was surprised to find his pocket book and cigarette case still there.

‘They appear to have taken only my watch,’ he said. His words seemed to be coming from a long way away as the reality slipped into his head and took root. It had not been a random robbery. Indeed, not a robbery at all, but a lesson, as the man had said.

Pushing the thought from his mind, Anatole pulled out a note and slipped it into the old man’s tobacco-stained fingers. ‘In gratitude for your assistance, my friend.’

The watchman looked down. A smile broke out. ‘Most generous, Monsieur.’

‘But no need to mention this to anyone, there’s a good chap. Now, if you could find me a cab?’

The old man touched his hat. ‘Whatever you say, sir.’