III

In early October 1955, Jack and Jackie Kennedy set sail for home, arriving in New York on the twelfth. Immediately, Jack headed for the Manhattan office of Dr. Janet Travell, an expert on pain management he had first visited a few months before. The muscle spasms in his lower left back had been bad on the trip, he told her, radiating out to his left leg and making him unable to put weight on it; he had been compelled to use crutches much of the time. He often could not reach his left foot to pull on a sock or sit in a low chair. Travell, in their earlier meeting, had determined that the left side of Kennedy’s body was smaller than his right—the left side of his face was smaller, his left shoulder was lower, and his left leg significantly shorter. Astonishingly, in all the years of medical treatment, no previous doctor had ever detected the problem, which, with every step, caused a vacillating movement and generated strain in the spinal muscles. Upon initial diagnosis, Travell had prescribed lifts for Jack’s left shoes and a lowered heel for his right, while also injecting him with procaine, more commonly known as Novocain. She now increased the dosage and suggested new exercises, then sent the patient on his way.

Kennedy found he liked Travell a great deal, liked the combination of her gentle woman’s touch and her authoritative demeanor, backed by top credentials; in the weeks to come, he would regularly slip out of Washington for a day and fly up to have an appointment with her. She considered him a model patient—accepting of, or at least not resentful of, his condition, always game to try any regimen that seemed reasonable.16

Travell’s efforts seemed to pay off. By the end of the year her patient was up to 168 pounds, his most ever, and he felt better than he had in a long time. His features had filled out, matured, as had his voice; he no longer looked or sounded younger than his years.

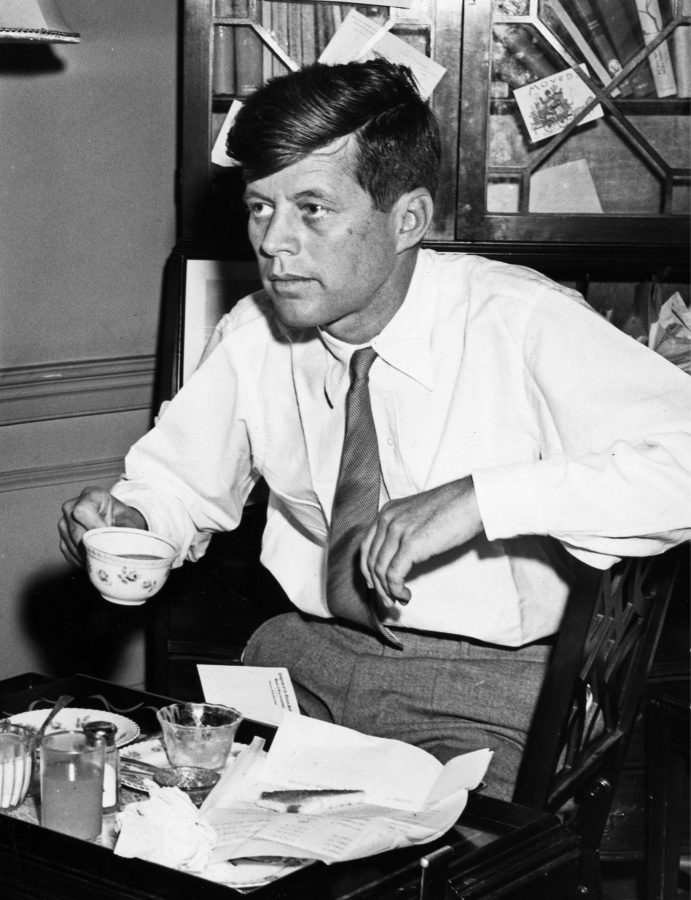

Back on the job in Washington, fall 1955.

Jackie, for her part, suffered a physical setback of her own. On a fall weekend in Hyannis Port, she gamely agreed to play in the family’s usual football scrimmage. Going out for a pass, she tripped and fell, crying out in pain. At New England Baptist Hospital, doctors confirmed an ankle fracture and kept her for five days, outfitting her with a cast below the knee. While recovering at her mother’s Merrywood estate, in Northern Virginia, Jackie carried on the house hunt she had begun in the late spring before departing for Europe. Something kept bringing her back to Hickory Hill, a large three-story brick Georgian Colonial home in McLean, with guest quarters, stables, and a pool. The Potomac River ran nearby. She loved the tall trees and the rolling hills and the stables (she still liked to ride when circumstances permitted), and Jack was tickled by the historical connections: during the Civil War it had been General George B. McClellan’s command post. They closed on the property for $125,000, and Jackie set about remodeling the main house extensively. Maybe, she thought, this could be the home that would make their marriage a happy one, where they could raise a family and live for the rest of their lives. Here, too, the close of 1955 brought happy news: Jackie found out she was pregnant.17

All the while that autumn, Dwight Eisenhower’s heart attack and prognosis dominated the national headlines, with daily announcements marking his progress as he convalesced in Denver. On October 10 the president sat in the sun for a few minutes outside his Army hospital in Denver; on the fourteenth, his sixty-fifth birthday, he was photographed in a wheelchair on the hospital roof, looking relaxed and smiling. But the image belied the seriousness of his condition. Not until October 23 did he stand upright for the first time, and only on the twenty-sixth did he take unassisted steps—and then only a few feet across his bedroom. By November 11, forty-nine days after the heart attack, Eisenhower had improved sufficiently to be flown to Washington, where a large crowd greeted him at National Airport and others lined the streets en route to the White House. Even now he was weak, mostly screened from public view by his aides and doctors, and he spent the rest of 1955 at his home in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Only on January 9, 1956, did he resume his official duties in Washington—five months after departing the capital for his fateful summer holiday.18

Would he run for reelection? Political handicappers were uncertain as the year turned, which added intrigue in particular to the race for the Democratic nomination. (Republicans remained in stand-by mode.) Adlai Stevenson announced his candidacy on November 15, and Estes Kefauver followed on December 17. Averell Harriman waited in the wings, and there were well-founded rumors that Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas, the powerful Senate majority leader, looked to get in. This latter prospect intrigued Joe Kennedy. To his mind, Johnson would be a stronger candidate for the Democrats than any of the other possibilities, including Stevenson; though a healthy Eisenhower would likely best all of them, the margin would be narrower with Johnson at the top of the ticket. So the Ambassador devised a plan, one he laid out to Johnson ally and former FDR adviser Tommy Corcoran: if Johnson would declare his candidacy and promise to select Jack as his running mate, he, Joe Kennedy, would arrange financing for the ticket. Corcoran duly reported the offer to Johnson, who turned it down, claiming he wasn’t running.19

Jack, it seems, never embraced the scheme, and it didn’t surprise him that Johnson said no. To Jack’s way of thinking, if the Texan coveted the nomination (and Jack had no doubt that he did), it made little sense for him to tie his hands in the way Joe Kennedy’s offer demanded. For that matter, Lyndon Johnson was at best a long shot for the top spot—by Jack’s calculation Adlai Stevenson remained the clear front-runner. Anyone seeking the number-two spot should focus his attention on him.

This was sound thinking on Jack’s part. Stevenson may have lost in 1952, but he remained the titular head of the Democratic Party, deeply popular with many state leaders and rank-and-file members, and still the runaway favorite among the party’s intellectuals. His loss in 1952, though admittedly lopsided, seemed in hindsight foreordained: no Democrat, in this line of reasoning, would have had a prayer of besting the popular Eisenhower, especially with the malaise of twenty straight years of Democratic rule and with the nation mired in an unpopular war in Korea. Even then, Stevenson had performed better than many gave him credit for—he racked up three million more votes nationally than Harry Truman had mustered in 1948. Since the election, moreover, Stevenson had only solidified his power position, giving well-received speeches around the country and winning accolades for his fundamental decency, his disavowal of bombast and banality, and his steadfast appeal to virtue and reason. “When demagoguery and deceit become a national political movement,” he asserted in Miami Beach in early 1954, in pointed reference to Joseph McCarthy, “we Americans are in trouble; not just Democrats, but all of us.”20

Jack saw the appeal of Stevenson and his message and shared his fundamental philosophy—Jack’s own book, now deep in production, stressed the vital importance of rational, fact-based discourse in a democracy, and he shared the Illinoisan’s affinity for blending poetry with power. He and Stevenson were not close allies, but in this period they got on well with each other.21 And it mattered to him that Jackie admired Stevenson and wanted him for the top of the ticket, and that most of the friends the couple saw socially did, too. It intrigued Jack in this regard that the low-level buzz about a potential Stevenson-Kennedy ticket had not dissipated in the fall months; if anything, it had picked up.22 Accordingly, he asked Ted Sorensen to undertake a study of the possible electoral benefits of having a Catholic vice presidential pick on the Democratic side. Sorensen took up the task eagerly, gathering a wide range of materials, journalistic as well as academic. He also went further, suggesting on November 22 that Kennedy endorse Stevenson at a high-profile news conference in Washington. Sorensen’s rationale was twofold: an early public endorsement would bring Kennedy increased exposure and, “more important, provide an opportunity to clear up all doubts about your health, which is the one question I still hear frequently raised around here when your name is discussed as a possibility for the ticket.”23 (Jack’s endorsement of Stevenson would come on March 8, 1956. He delayed the move, he told journalists, in order to give Stevenson the “best possible assist” in advance of the upcoming New Hampshire primary.24)

Sorensen’s seventeen-page study, completed in the winter of 1956 and titled “The Catholic Vote in 1952 and 1956,” examined the results among Catholic voters in fourteen pivotal states in the North and the West, all of them previously Democratic, that had gone for Eisenhower over Stevenson in 1952 and, the report concluded, swung the election to the Republican. Using polling data, election returns, and academic research, Sorensen argued that the Catholic vote within those states had long been critical—without it, the Democrats would have lost the elections of 1940, 1944, and 1948. Moreover, Stevenson, in part because of his divorce and the perception of him as a liberal and an intellectual who was insufficiently strong on Communism, in 1952 had received lower percentages than Catholic Democratic candidates for the House and Senate in these states. For Sorensen, the conclusion was inescapable: if these traditionally Democratic voters could be brought back to the fold by means of a Catholic running mate for Stevenson, it could be decisive, combining with Democratic strengths in the South to bring the former Illinois governor success. Conversely, without these voters he had no realistic path to victory.

But what about Al Smith’s defeat in 1928? Didn’t that show the immense risk of having a Catholic on the ticket? Not remotely, the study said—1928 was a GOP year, a year for “dry” supporters of Prohibition. It wouldn’t have mattered who the Democrats ran—he would have been vanquished. Of the states Smith lost, only four, all in the South, had been solidly Democratic in the years prior. Since then the picture had changed, and the Catholic vote now loomed more important than ever. Indeed, Sorensen suggested, in an indirect comment on the other potential vice presidential picks, Democratic chances in 1956 depended less on the farm vote or the southern vote than on reclaiming broad backing among Catholics.25

“Catholic voting strength is currently at its peak,” Sorensen wrote, quoting pollster Samuel Lubell, “in view of the maturing of the offspring of the Italians, Czechs, and other former immigrant elements.” Moreover, Sorensen stressed, ample research indicated that Catholics turned out to vote in greater proportions than did non-Catholics, a key point under any circumstances but especially given the nation’s current population distribution: Catholics were particularly concentrated in fourteen crucial states with 261 votes in the electoral college (five fewer than were needed in 1956 to win the presidency).26

Even before Sorensen’s study was completed, he and Kennedy quietly pushed its findings on sympathetic journalists. Fletcher Knebel, a witty and acerbic Look columnist who wrote political novels (including Seven Days in May) on the side, came away impressed after a meeting with the two men in February in which he received a rundown of the report. Kennedy, he wrote, had “all the necessary Democratic assets” in a vice president: good looks, youth, an outstanding war record, liberal policy positions, and exceptional vote-getting ability. His religion, moreover, far from being a liability in a national race, would be a boon, Knebel suggested, generating big turnouts in northern and eastern states with large Catholic populations.27

IV

There the matter might have rested, were it not for two other developments in early 1956 that served to raise Kennedy’s stature. The first was the publication, in early January, of Profiles in Courage. In advance of the release, there had appeared a substantial excerpt in The New York Times Magazine, titled “The Challenge of Political Courage” and culled mostly from chapter 1, as well as shorter pieces in The Boston Globe, Harper’s, Reader’s Digest, and Collier’s.28 These prepublication efforts, vital in an age when glossy magazines were a hugely important source of information for the mass of Americans—Reader’s Digest and Collier’s had circulations of 10 million and 3.7 million, respectively—spurred advance orders of the book, and Kennedy received further encouragement from glowing reviews in prominent places. In a front-page assessment in The New York Times Book Review, political reporter Cabell Phillips gushed that it was “refreshing and enlightening to have a first-rate politician write a thoughtful and persuasive book about political integrity,” featuring senators each of whom “at some moment of crisis staked his principles against the massed furies of bigotry, sectionalism, and conformity.” An empathetic observer, the author was “no dilettante at his trade, but a solid journeyman full of ideals, but few illusions. His book is the sort to restore respect for a venerable and much abused profession.”29

In a similar vein, The Saturday Evening Post praised Kennedy for recognizing “the necessity of compromise, to make democratic government work at all,” and for understanding a senator’s need to “act according to his own conscience regardless of what his constituents may think.” According to the Chicago Tribune, it was “a remarkable book….He writes brilliantly about a handful of American statesmen who, at crucial times in history, have displayed a rare kind of greatness.”30 Erwin D. Canham, writing in The Christian Science Monitor, cautioned that the author had better watch his step going forward, “for he has set up high standards of political integrity for comparison.” But that, in its way, was a compliment to Kennedy, Canham went on: “That a U.S. senator, a young man of independent means with a gallant and thoughtful background, should have produced this study is as remarkable as it is helpful. It is a splendid flag that Senator Kennedy has nailed to his mast. May he keep it there.” And so it went, with praise coming from The Houston Chronicle (“wholly engrossing”), the Cleveland Plain Dealer (“as fine a book as we are likely to get all year”), The Wall Street Journal (“a heartening and extremely spirited book”), and other papers across the nation.

In Boston, the City Council passed a resolution mandating that the School Committee incorporate Profiles in Courage as a central part of its history curriculum, and council member Gabriel F. Piemonte praised the volume as a “great lesson in democracy.” In other cities, too, the book in short order became a staple on high school reading lists, in many places remaining there for years to come.31

A few dissonant voices could be heard. Charles Poore, in a review in The New York Times’s Books of the Times section, found it troubling that Kennedy lauded men who “showed their most conspicuous courage in defying the very forces that had chosen them for leadership.” In his eloquent defense of the actions of Edmund G. Ross, for example, whose lonely vote in 1868 saved President Andrew Johnson from impeachment and thereby also upheld the Constitution, Kennedy had not taken “sufficient account of the enduring good sense of the American people as a whole who, as in the past, always will preserve constitutional government, no matter what the demagogues advocate in any passing time.” Poore also wondered if it really was immaterial, as Kennedy claimed, whether another of his subjects, George Norris, was right or wrong on an issue, or only that Norris showed courage and was true to himself. Shouldn’t the purpose to which the courage was put matter, too? “It almost urges us to admire courage as courage, no matter where it appears. And this has its repugnant aspects….Our view of true courage, somehow, is inextricably woven into the fabric of the cause for which it is displayed.” Poore nonetheless praised Profiles in Courage as “splendidly readable” and deeply impressive for having such an “extraordinarily varied” cast of characters. Kennedy, he wrote approvingly, “is a practical man as well as a connoisseur of idealists,” a man who “appreciates Lord Melbourne’s saying that he would like to be sure of anything as Macaulay seemed to be of everything.”32

Sales were brisk from the start, and the book shot up the bestseller lists. It stayed there for many months. (Within three years it had sold 180,000 copies in hardback and half a million in paperback.) No longer could anyone consider John Kennedy just another freshman senator; now he was dubbed the unofficial historian of the upper chamber, and a respected champion of political integrity. With Soviet-led Communism posing a threat to the American way of life, the book affirmed for many readers the ability of democracy to triumph by producing leaders who put the national interest before selfish careerist ambition, who lived by the adage that no one has a monopoly on truth and therefore reasonable people can differ on the solutions to complex social and political problems. Foreign translations soon appeared, in languages from Hebrew to Japanese to Gujarati. On February 7, a month after publication, Kennedy was the featured speaker at the National Book Awards dinner in New York City, where he was photographed in the esteemed literary company of John O’Hara and W. H. Auden.33

Later, and especially after the book was awarded the 1957 Pulitzer Prize for Biography, critics would fault what they considered the deception of publishing a book under the name of a person who hadn’t actually written it. Some were still leveling the charge decades after Kennedy’s death.34 The objection was largely baseless. For one thing, Kennedy had a bigger role in the writing, and certainly in the conception and framing of the book, than many of these analysts suggested; the book’s broad themes and overarching structure were his. Friends who had visited in Florida attested to his hard work on the manuscript, as did secretaries who took his dictation, as did, with great vehemence, Jackie Kennedy.35 (Without Sorensen or Jules Davids, Kennedy likely would have produced a similar book, if less felicitous in its prose; without Kennedy, on the other hand, Profiles in Courage would not have existed.) For another, it was standard practice for American politicians in midcentury—and later—to get significant assistance on books that appeared under their name alone. Everyone in Congress knew, for example, that Crime in America, a recent bestseller by Estes Kefauver, had mostly been written for him by his staff.36

Certainly it never occurred to Kennedy or Sorensen or anyone else involved in the project that they might be acting unethically, then or afterwards. Sorensen contributed mightily to the senator’s speeches and articles; why should he not help write a book? Arguably, Kennedy should have refused the Pulitzer, but it’s hard to imagine him (or anyone else in his position) actually doing so—such a move would have amounted to a self-declaration of fraudulence and possibly done lasting damage to his reputation. More to the point, in core respects Kennedy was the book’s author. He himself never wavered from that conviction, and to the end of his days he would consider winning the Pulitzer perhaps the proudest moment of his life.37