RULE 7

PURSUE WHAT IS MEANINGFUL (NOT WHAT IS EXPEDIENT)

GET WHILE THE GETTING’S GOOD

LIFE IS SUFFERING. THAT’S CLEAR. There is no more basic, irrefutable truth. It’s basically what God tells Adam and Eve, immediately before he kicks them out of Paradise.

Unto the woman he said, I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.

And unto Adam he said, Because thou hast hearkened unto the voice of thy wife, and hast eaten of the tree, of which I commanded thee, saying, Thou shalt not eat of it: cursed is the ground for thy sake; in sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life;

Thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to thee; and thou shalt eat the herb of the field;

By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return. (Genesis 3:16-19. KJV)

What in the world should be done about that?

The simplest, most obvious, and most direct answer? Pursue pleasure. Follow your impulses. Live for the moment. Do what’s expedient. Lie, cheat, steal, deceive, manipulate—but don’t get caught. In an ultimately meaningless universe, what possible difference could it make? And this is by no means a new idea. The fact of life’s tragedy and the suffering that is part of it has been used to justify the pursuit of immediate selfish gratification for a very long time.

Short and sorrowful is our life, and there is no remedy when a man comes to his end, and no one has been known to return from Hades.

Because we were born by mere chance, and hereafter we shall be as though we had never been; because the breath in our nostrils is smoke, and reason is a spark kindled by the beating of our hearts.

When it is extinguished, the body will turn to ashes, and the spirit will dissolve like empty air. Our name will be forgotten in time and no one will remember our works; our life will pass away like the traces of a cloud, and be scattered like mist that is chased by the rays of the sun and overcome by its heat.

For our allotted time is the passing of a shadow, and there is no return from our death, because it is sealed up and no one turns back.

Come, therefore, let us enjoy the good things that exist, and make use of the creation to the full as in youth.

Let us take our fill of costly wine and perfumes, and let no flower of spring pass by us.

Let us crown ourselves with rosebuds before they wither.

Let none of us fail to share in our revelry, everywhere let us leave signs of enjoyment, because this is our portion, and this our lot.

Let us oppress the righteous poor man; let us not spare the widow nor regard the gray hairs of the aged.

But let our might be our law of right, for what is weak proves itself to be useless. (Wisdom 2:1-11, RSV).

The pleasure of expediency may be fleeting, but it’s pleasure, nonetheless, and that’s something to stack up against the terror and pain of existence. Every man for himself, and the devil take the hindmost, as the old proverb has it. Why not simply take everything you can get, whenever the opportunity arises? Why not determine to live in that manner?

Or is there an alternative, more powerful and more compelling?

Our ancestors worked out very sophisticated answers to such questions, but we still don’t understand them very well. This is because they are in large part still implicit—manifest primarily in ritual and myth and, as of yet, incompletely articulated. We act them out and represent them in stories, but we’re not yet wise enough to formulate them explicitly. We’re still chimps in a troupe, or wolves in a pack. We know how to behave. We know who’s who, and why. We’ve learned that through experience. Our knowledge has been shaped by our interaction with others. We’ve established predictable routines and patterns of behavior—but we don’t really understand them, or know where they originated. They’ve evolved over great expanses of time. No one was formulating them explicitly (at least not in the dimmest reaches of the past), even though we’ve been telling each other how to act forever. One day, however, not so long ago, we woke up. We were already doing, but we started noticing what we were doing. We started using our bodies as devices to represent their own actions. We started imitating and dramatizing. We invented ritual. We started acting out our own experiences. Then we started to tell stories. We coded our observations of our own drama in these stories. In this manner, the information that was first only embedded in our behaviour became represented in our stories. But we didn’t and still don’t understand what it all means.

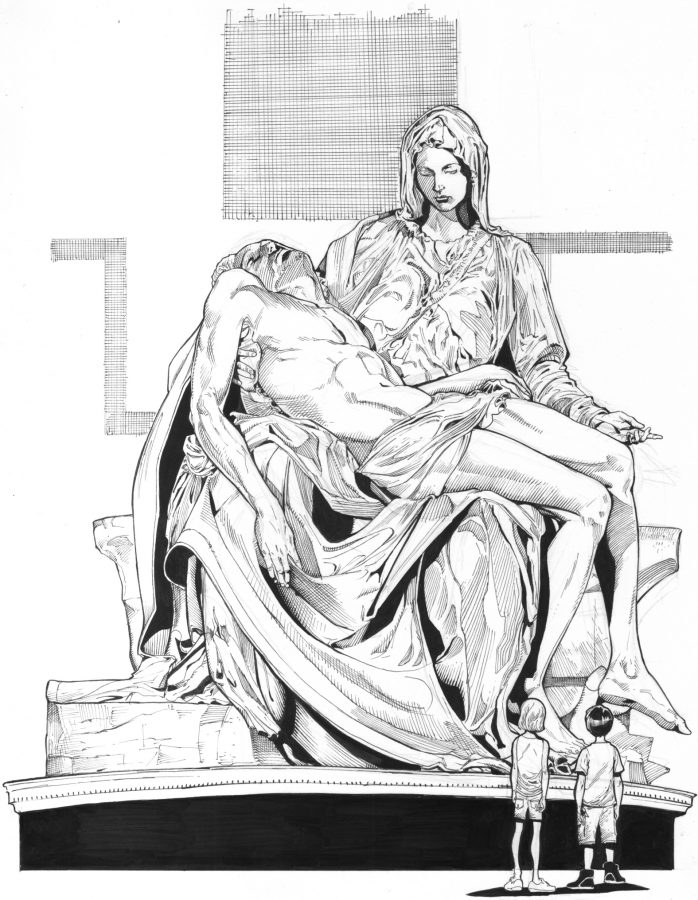

The Biblical narrative of Paradise and the Fall is one such story, fabricated by our collective imagination, working over the centuries. It provides a profound account of the nature of Being, and points the way to a mode of conceptualization and action well-matched to that nature. In the Garden of Eden, prior to the dawn of self-consciousness—so goes the story—human beings were sinless. Our primordial parents, Adam and Eve, walked with God. Then, tempted by the snake, the first couple ate from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, discovered Death and vulnerability, and turned away from God. Mankind was exiled from Paradise, and began its effortful mortal existence. The idea of sacrifice enters soon afterward, beginning with the account of Cain and Abel, and developing through the Abrahamic adventures and the Exodus: After much contemplation, struggling humanity learns that God’s favour could be gained, and his wrath averted, through proper sacrifice—and, also, that bloody murder might be motivated among those unwilling or unable to succeed in this manner.

The Delay of Gratification

When engaging in sacrifice, our forefathers began to act out what would be considered a proposition, if it were stated in words: that something better might be attained in the future by giving up something of value in the present. Recall, if you will, that the necessity for work is one of the curses placed by God upon Adam and his descendants in consequence of Original Sin. Adam’s waking to the fundamental constraints of his Being—his vulnerability, his eventual death—is equivalent to his discovery of the future. The future: that’s where you go to die (hopefully, not too soon). Your demise might be staved off through work; through the sacrifice of the now to gain benefit later. It is for this reason—among others, no doubt—that the concept of sacrifice is introduced in the Biblical chapter immediately following the drama of the Fall. There is little difference between sacrifice and work. They are also both uniquely human. Sometimes, animals act as if they are working, but they are really only following the dictates of their nature. Beavers build dams. They do so because they are beavers, and beavers build dams. They don’t think, “Yeah, but I’d rather be on a beach in Mexico with my girlfriend,” while they’re doing it.

Prosaically, such sacrifice—work—is delay of gratification, but that’s a very mundane phrase to describe something of such profound significance. The discovery that gratification could be delayed was simultaneously the discovery of time and, with it, causality (at least the causal force of voluntary human action). Long ago, in the dim mists of time, we began to realize that reality was structured as if it could be bargained with. We learned that behaving properly now, in the present—regulating our impulses, considering the plight of others—could bring rewards in the future, in a time and place that did not yet exist. We began to inhibit, control and organize our immediate impulses, so that we could stop interfering with other people and our future selves. Doing so was indistinguishable from organizing society: the discovery of the causal relationship between our efforts today and the quality of tomorrow motivated the social contract—the organization that enables today’s work to be stored, reliably (mostly in the form of promises from others).

Understanding is often acted out before it can be articulated (just as a child acts out what it means to be “mother” or “father” before being able to give a spoken account of what those roles mean).116 The act of making a ritual sacrifice to God was an early and sophisticated enactment of the idea of the usefulness of delay. There is a long conceptual journey between merely feasting hungrily and learning to set aside some extra meat, smoked by the fire, for the end of the day, or for someone who isn’t present. It takes a long time to learn to keep anything later for yourself, or to share it with someone else (and those are very much the same thing as, in the former case, you are sharing with your future self). It is much easier and far more likely to selfishly and immediately wolf down everything in sight. There are similar long journeys between every leap in sophistication with regard to delay and its conceptualization: short-term sharing, storing away for the future, representation of that storage in the form of records and, later, in the form of currency—and, ultimately, the saving of money in a bank or other social institution. Some conceptualizations had to serve as intermediaries, or the full range of our practices and ideas surrounding sacrifice and work and their representation could have never emerged.

Our ancestors acted out a drama, a fiction: they personified the force that governs fate as a spirit that can be bargained with, traded with, as if it were another human being. And the amazing thing is that it worked. This was in part because the future is largely composed of other human beings—often precisely those who have watched and evaluated and appraised the tiniest details of your past behavior. It’s not very far from that to God, sitting above on high, tracking your every move and writing it down for further reference in a big book. Here’s a productive symbolic idea: the future is a judgmental father. That’s a good start. But two additional, archetypal, foundational questions arose, because of the discovery of sacrifice, of work. Both have to do with the ultimate extension of the logic of work—which is sacrifice now, to gain later.

First question. What must be sacrificed? Small sacrifices may be sufficient to solve small, singular problems. But it is possible that larger, more comprehensive sacrifices might solve an array of large and complex problems, all at the same time. That’s harder, but it might be better. Adapting to the necessary discipline of medical school will, for example, fatally interfere with the licentious lifestyle of a hardcore undergraduate party animal. Giving that up is a sacrifice. But a physician can—to paraphrase George W.—really put food on his family. That’s a lot of trouble dispensed with, over a very long period of time. So, sacrifices are necessary, to improve the future, and larger sacrifices can be better.

Second question (set of related questions, really): We’ve already established the basic principle—sacrifice will improve the future. But a principle, once established, has to be fleshed out. Its full extension or significance has to be understood. What is implied by the idea that sacrifice will improve the future, in the most extreme and final of cases? Where does that basic principle find its limits? We must ask, to begin, “What would be the largest, most effective—most pleasing—of all possible sacrifices?” and then “How good might the best possible future be, if the most effective sacrifice could be made?”

The biblical story of Cain and Abel, Adam and Eve’s sons, immediately follows the story of the expulsion from Paradise, as mentioned previously. Cain and Abel are really the first humans, since their parents were made directly by God, and not born in the standard manner. Cain and Abel live in history, not in Eden. They must work. They must make sacrifices, to please God, and they do so, with altar and proper ritual. But things get complicated. Abel’s offerings please God, but Cain’s do not. Abel is rewarded, many times over, but Cain is not. It’s not precisely clear why (although the text strongly hints that Cain’s heart is just not in it). Maybe the quality of what Cain put forward was low. Maybe his spirit was begrudging. Or maybe God was vexed, for some secret reasons of His own. And all of this is realistic, including the text’s vagueness of explanation. Not all sacrifices are of equal quality. Furthermore, it often appears that sacrifices of apparently high quality are not rewarded with a better future—and it’s not clear why. Why isn’t God happy? What would have to change to make Him so? Those are difficult questions—and everyone asks them, all the time, even if they don’t notice.