Mutual acquaintances spotted another thing they had in common: they were competitive, including with each other. Early in the relationship, they often played Monopoly or Chinese checkers or word games such as Categories, at which Jack often excelled. It burned him and intrigued him when she held her own and sometimes bested him in these contests. (In Scrabble, she proved almost unbeatable.) “From the beginning there was a playful element between them,” Lem Billings recalled. “Jackie gave him a good match: that’s one of the things Jack liked. But there was a serious element too. Who was going to win?”16

“He saw her as a kindred spirit,” Billings went on. “I think he understood that the two of them were alike. They had both taken circumstances that weren’t the best in the world when they were younger and learned how to make themselves up as they went along.”17 Their pasts, that is to say, affected them in complex ways. Jackie didn’t have Jack’s health problems growing up, but she and her younger sister, Lee, endured a trying childhood in a dysfunctional family environment. Their parents, John Vernou Bouvier III, a flamboyant New York Stock Exchange member who claimed to trace his lineage to French soldiers who fought in the American Revolutionary War, and Janet Bouvier (née Lee), the daughter of a self-made millionaire, engaged in frequent alcohol-fueled fights over his serial womanizing and chronic financial failings. Then each would badmouth the other in front of the girls. We can only speculate about the effect of this behavior on the daughters; to a degree, at least, Jackie seems to have responded by retreating from the world and from other people. She found escape and refuge in books and horses, competing from an early age in equestrian competitions and even winning two events in the junior ranks at the equestrian national championships at Madison Square Garden.

Jack Bouvier, whose French immigrant ancestors in Philadelphia had experienced anti-Catholic prejudice not unlike that endured by County Wexford’s Patrick Kennedy, was as charismatic as he was erratic. With the dark good looks and pencil-style mustache of Clark Gable, he was vain and self-absorbed. He exercised in the gym regularly and used a sunlamp to stay tan, and didn’t mind at all when he acquired nicknames that bespoke his playboy ways—the Black Orchid, the Black Sheik, and, most commonly, Black Jack. By all accounts he was terrific company, a raconteur and bon vivant whose lecherous ways had compensating qualities, at least in the eyes of some women. “Bouvier was unusual among the philanderers of his day,” one of his paramours said. “Women were not just collectibles for him. He actually liked their company, liked the feminine perspective and the social quality of women’s lives.” Both of his daughters felt closer to him than to their mother, even after Jack and Janet divorced and she married Hugh D. “Hughdie” Auchincloss, a kindly, serene Episcopalian and Standard Oil heir from Virginia. Janet, a social striver of the first order, had a fierce temper; she often took out her frustrations on her daughters, in particular Jackie, faulting her looks and clothing choices. Even Jackie’s studiousness and love of books came in for rebuke—like many women of her class and period, Janet lived by the philosophy that men frowned on women who had their own intellectual interests and professional goals; accordingly, her daughters should cultivate the skills required to make men feel comfortable and important, and direct their own ambitions toward being effective homemakers.18

“All the fighting had an impact on both girls, of course,” said Truman Capote, who got to know both Bouvier sisters and became especially close with Lee. “It made them both terribly cautious, a little afraid of people and relationships in general….Even at that age, I think [Jackie] could appreciate that her mother was this sort of hideous control freak, a cold fish with social ambitions, and her father was a naughty, naughty boy who kept getting caught with his hand in the cookie jar. Of course, both girls loved him more. Who wouldn’t, given the choice?”19

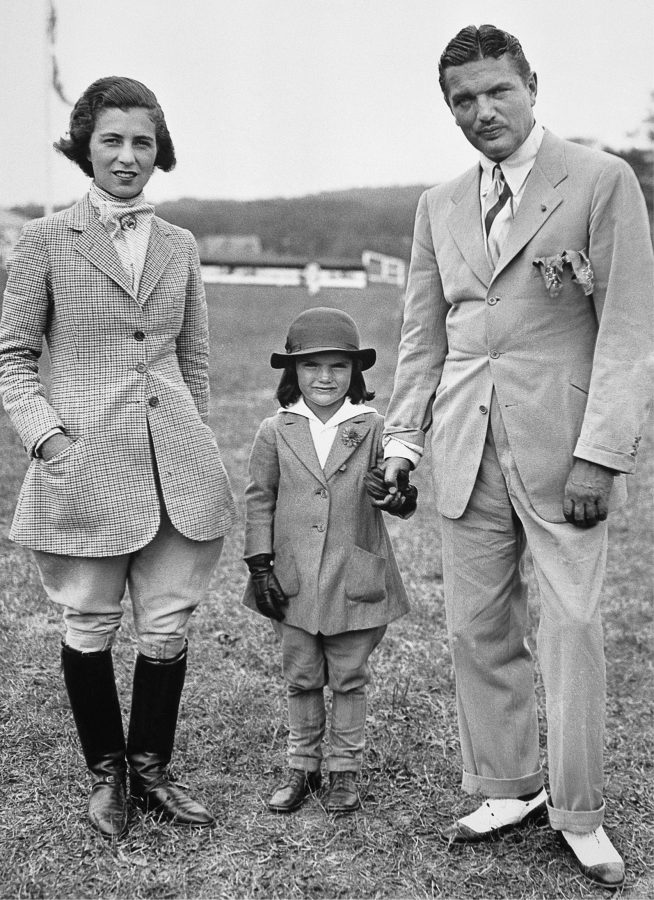

Young Jacqueline with her parents at the Southampton Riding and Hunt Club’s sixth annual Horse Show, August 1934.

According to biographer Barbara Leaming, Jackie internalized many of her mother’s harshest judgments about her—she was too tall, at five foot seven, too dark, too flat-chested, too boyish in figure. “In view of what Janet insisted was her utter lack of physical allure, she cultivated seductive mannerisms such as a whispery, baby voice….She trained herself to behave in an extremely flirtatious manner and presented herself as a fragile airhead, the antithesis of the strong, clever, curious young woman she really was.”20

At fifteen, Jackie was enrolled at Miss Porter’s School, in Farmington, Connecticut, one of the most respected finishing schools in New England, which still operated by its founding philosophy of a century before, that the core purpose of a young woman’s education was to make her a more pleasing companion to her husband. Jackie chafed against this culture—in the school’s yearbook she listed her ambition in life as “Not to be a housewife”—but only to a degree: she did not appear to question, either then or in the years that followed, the notion that it should be a chief goal in life to “marry well,” or the corollary idea that a woman should live life through her man and make his successes her own.21 A strong student, Jackie maintained an A-minus average and also involved herself in the drama and riding clubs and helped edit the school newspaper. But she also treasured solitude: when the other girls socialized after evening study hall, her roommate remembered, “Jackie seldom joined in, happily staying in her room, reading, writing poetry or drawing…by nature she was a loner.”22

From Miss Porter’s she moved on to Vassar College, in Poughkeepsie, New York, but not before being presented to society in Newport, Rhode Island, where the Auchinclosses maintained an estate. (“Queen Deb of the Year,” wrote one New York society columnist, “is Jacqueline Bouvier, a regal brunette who has classic features and the daintiness of a Dresden porcelain. She has poise, is soft-spoken and intelligent, everything the leading debutante should be.”)23 At Vassar, Jackie, part of an entering class of approximately two hundred women, took courses in literature and history and joined the college newspaper staff, the drama group (as a costume designer), and the art club. Well liked by the other students, she could also be secretive, projecting a sense of apartness, even aloofness. “You never knew what she was thinking or what she was really feeling,” one classmate said.24

The sense of mystery may have added to her allure among college men, who came calling with regularity. “Young men were constantly trying every kind of trick to make her go out with them,” said Letitia Baldrige, who had been a year ahead of Jackie at Miss Porter’s and would continue to know her in the decades to come (including as White House social secretary). “Her classic good looks were complemented by her sense of style, which had been apparent from her early teens.” She would put on a simple skirt and shirt, add just the right belt, and, with her perfect posture and bearing, come off exquisite, Baldrige marveled. “Nothing ever looked wrong on her.” But though Jackie accepted a number of dates—she went to football games and dances at Princeton, Yale, and Harvard, among other places—she avoided committing herself. When returning from a date with a young man in a taxi, she would tell the driver, “Hold your meter.” Crestfallen escorts realized they would not get beyond the front door.25

Jackie didn’t take to Vassar—she thought it hidebound and provincial—but she loved her junior year in France, in 1949–50, most of which she spent in Paris, studying French history and art history at the Sorbonne. All the instruction was in French. It thrilled her, she reflected afterwards, that here she didn’t have to cloak her smarts or the fact that she had genuine intellectual interests, but she also led a full social life, venturing out on an almost nightly basis from her rented room on avenue Mozart, in the fashionable if slightly stuffy sixteenth arrondissement, sipping coffee or wine at the Ritz Bar or Café de Flore or La Coupole and hitting the nightspots on both banks of the Seine until all hours. She frequented the museums and galleries, the opera and the ballet. Her French, middling at the outset, became fluent. She also went on dates, seeing a French diplomat’s son as well as an aspiring young writer named Ormonde de Kay and, some accounts say, losing her virginity in an elevator to a dashing young American writer, John P. Marquand Jr., son of the novelist. (The elevator to his apartment supposedly “stalled” between floors, a trick Marquand had used with women before her.)26

Jackie did not return to Vassar for senior year. She sought a more urban environment and transferred to George Washington University, from which she graduated in 1951 with a degree in French literature. She then explored, intriguingly, a job with the CIA, but either she did not pursue it or she was not granted an interview. Instead, she entered and won Vogue magazine’s Prix de Paris contest for excellence in design and editorial ability, besting twelve hundred other entrants for the grand prize and the chance to live and work for the magazine in Paris.*2, 27 She turned down the award—her mother and stepfather felt she had already spent too much time abroad, and she herself worried that if she went she might never come back—and instead took a position with the Washington Times-Herald (where Inga Arvad had also worked) as the “Inquiring Camera Girl” who asked people lighthearted questions and took their photograph. (“Winston Churchill once observed that marriages have a better chance of survival when the spouses don’t breakfast together. Do you agree?” “Should men wear wedding rings?” “If you had a date with Marilyn Monroe, what would you talk about?” “Would you like your son to grow up to be president?”) Her weekly starting salary was $42.50; within a few months the figure rose to $56.75. On one occasion, she made the newly elected senator from Massachusetts her subject, snapping his photo and posting his answer to a question concerning the role of pages (assistants) in the work of the Senate.28