CHAPTER 8

The bell for Vespers had long since fallen silent by the time Pelletier finally emerged from the Tour Pinte.

Feeling every one of his fifty-two years, Pelletier lifted aside the curtain and walked back into the Great Hall. He rubbed his temples with tired hands, trying to ease the persistent, hammering ache in his head.

Viscount Trencavel had spent the time since the end of Council with the strongest of his allies, talking about how best to approach the Count of Toulouse. Talking for hour upon hour. One by one, decisions had been taken and messengers had galloped out from the Chateau Comtal bearing letters not only to Raymond VI, but also to the Papal Legates, to the Abbot of Citeaux and Trencavel’s consuls and viguiers in Béziers. The chevaliers who were to accompany the Viscount had been informed. In the stables and the smithy, preparations were already in hand and would continue most of the night.

The chamber was filled with a hushed but expectant silence. Because of tomorrow’s early departure, instead of the planned banquet there was to be a more informal meal. Long trestle tables had been set out, unclothed, in rows running from north to south across the room. Candles flickered dimly in the centre of each table. In the high wall sconces, the torches were already burning fiercely, setting the shadows dancing and flickering.

At the far end of the room, servants came in and out, carrying dishes that were more plentiful than ceremonial. Hart, venison, chicken drumsticks with capsicum, earthenware bowls filled with beans and sausage and freshly baked white bread, purple plums stewed in honey, rose-coloured wine from the vineyards of the Corbières and pitchers of ale for those with weaker heads.

Pelletier nodded his approval. He was pleased. In his absence, François had deputised well. Everything looked as it should and of a level of courtesy and hospitality Viscount Trencavel’s guests had the right to expect.

François was a good servant, despite his unfortunate start in life. His mother had been in the service of Pelletier’s French wife, Marguerite, and was hanged for a thief when François was no more than a boy. His father was unknown. When his wife had died nine years ago, Pelletier had taken François on, trained him and given him a position. From time to time, he allowed himself to feel satisfaction at how well François had turned out.

Pelletier walked out into the Cour d’Honneur. The air was cool here and he lingered a while in the doorway. Children were playing around the well, earning a slap on the legs from their nurses when the boisterous games got too rowdy. Older girls strolled arm in arm in the twilight, talking, whispering their secrets to one another.

At first he didn’t notice the small, dark-haired boy sitting cross-legged on the wall by the chapel.

‘Messire! Messire!’ cried the boy, scrambling to his feet. ‘I got something for you.’

Pelletier took no notice. ‘Messire,’ The boy persisted, tugging at his sleeve to attract his attention. ‘Intendant Pelletier, please. Important.’

He felt something being pushed into his hand. He looked down to see it was a letter written on heavy, cream parchment. His heart lurched. On the outside was his own name, inscribed in a familiar, distinctive hand. Pelletier had persuaded himself he’d never see it again.

Pelletier grabbed the boy by the scruff of the neck. ‘Where did you get this?’ he demanded, shaking him roughly. ‘Speak.’ The boy wriggled like a fish on a line, trying to get free. ‘Tell me. Quick, now.’

‘A man gave it to me at the gate,’ the boy whimpered. ‘Don’t hurt me. I’ve done nothing.’

Pelletier shook him harder. ‘What sort of man?’

‘Just a man.’

‘You’ll have to do better than that,’ he said harshly, his voice rising. ‘There’s a sol in it for you if you can tell me what I want to know. Was the man young? Old? Was he a soldier?’ He paused. ‘A Jew?’

Pelletier fired question after question until he’d dragged the facts out of the boy. They didn’t amount to much. Pons told him he’d been playing with friends in the moat of the Chateau Comtal, trying to get across from one side of the bridge to the other without the guards catching them. At dusk, when the light was just beginning to fade, a man had approached them and asked if anybody knew Intendant Pelletier by sight. When Pons said he did, the man had given him a sol to deliver the letter. He said it was very important and very urgent.

There was nothing special about the man that marked him out. He was of middle years, neither old nor young. He was not especially dark, nor fair either. His face was unmarked, unblemished by either pox or fight. He hadn’t noticed if the man wore a ring, because his hands were concealed underneath his cloak.

Finally satisfied he had learned all he could, Pelletier reached into his purse and gave the boy a coin.

‘Here. This is for your trouble. Now, go.’

Pons didn’t wait to be told a second time. He wriggled out of Pelletier’s grasp and ran, as fast as his legs would carry him.

Pelletier headed back inside, holding the letter tight to his chest. He registered no one as he swept through the corridor leading to his chamber.

The door was locked. Cursing his own caution, Pelletier fumbled with the keys, his haste making him clumsy. François had lit the calèlhs, the oil lamps, and set his night tray with a jug of wine and two earthenware goblets on the table in the centre of the room, as he did every night. The highly polished brass surface of the tray gleamed in the flickering, golden light.

Pelletier poured himself a drink to steady his nerves, his head full of dusty images, memories of the Holy Land and the long, red shadows of the desert. Of the three books and the ancient secret contained within their pages.

The coarse wine was sour on his tongue and hit the back of his throat with a sting. He downed it in one, then refilled the goblet. Many times he’d tried to visualise how he would feel at this moment. Yet now it had finally come, he felt numb.

Pelletier sat down, placing the letter on the table between his outstretched hands. He knew what it said. It was the message he’d been both anticipating and dreading for many years, ever since he’d arrived in Carcassonne. In those days, the prosperous and tolerant lands of the Midi had seemed a safe hiding place.

As the seasons rolled one into the next, over time Pelletier’s expectations of being called upon diminished. Day-to-day life took over. Thoughts of the books faded from his mind. In the end, he had almost forgotten that he was waiting at all.

More than twenty years had passed since he’d last set eyes upon the author of the letter. Until this moment, he realised, he’d not even known if his teacher and mentor was still alive. It was Harif who had taught him to read in the shade of the olive groves on the hills outside Jerusalem.

It was Harif who’d opened his senses to a world more glorious, more magnificent than anything Pelletier had ever known. It was Harif who’d taught him to see that Saracens, Jews and Christians were following but different paths to the one God. And it was Harif who’d revealed to him that beyond all that was known lay a truth far older, more ancient, more absolute than anything the modern world had to offer.

The night of Pelletier’s initiation into the Noublesso de los Seres was as sharp and clear in his mind as if it was yesterday. The shimmering robes of gold and the bleached white altar cloth, as dazzling as the forts that glinted high on the hills above Aleppo among the cypress trees and orange groves. The smell of the incense, the rise and fall of the voices whispering in the darkness. Illumination.

That night, another lifetime ago, or so it seemed to Pelletier now, was when he had looked into the heart of the labyrinth and made a vow to protect the secret with his life.

He pulled the candle closer. Even without the authenticity of the seal, there could be no doubt that the letter was from Harif. He would recognise his hand anywhere, the distinctive elegance of his letters and the exact proportions of his script.

Pelletier shook his head, trying to dislodge the memories threatening to overwhelm him. He took a deep breath, then slipped his knife under the seal. The wax split open with a soft crack. He smoothed the parchment flat.

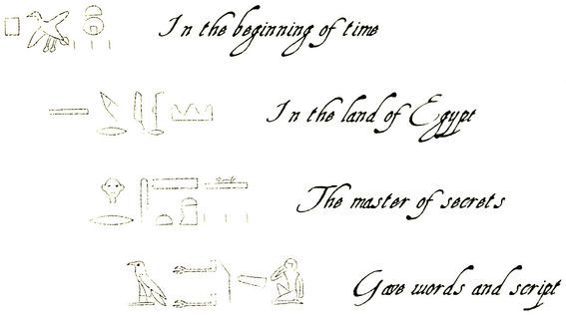

The letter was brief. Across the top of the sheet were the symbols Pelletier remembered from the yellow walls of the labyrinth cave in the hills outside the Holy City. Written in the ancient language of Harif’s ancestors, they meant nothing except to those initiated into the Noublesso.

Pelletier read the words aloud, the familiar sounds reassuring him, before turning to Harif’s letter.

Fraire

It is time. Darkness is coming to these lands. There is malice in the air, an evil that will destroy and corrupt all that is good. The texts are no longer safe in the plains of the Pays d’Oc. It is time for the Trilogy to be reunited. Your brother awaits you in Besiers, your sister in Carcassona. It falls to you to carry the books to a place of greater safety.

Make haste. The summer passes to Navarre will be closed by Toussaint, perhaps sooner if the snows come early. I shall expect you by the Feast Day of Sant-Miquel.

Pas a pas, se va luènh.

The chair creaked as Pelletier leaned sharply back. It was no more than he expected. Harif’s instructions were clear. He asked no more than Pelletier had once sworn to give. But yet, he felt as if his soul had been sucked out of his body leaving only a hollow space.

The pledge he had given to guard the books had been made willingly, but in the simplicity of youth. Now, at the end of his middle years, it was more complicated. He had fashioned a different life for himself in Carcassonne. He had other allegiances, others he loved and served.

Only now did he realise how completely he’d persuaded himself that the moment of reckoning would not come in his lifetime. That he would never be forced to choose between his loyalty and responsibility to Viscount Trencavel and his obligation to the Noublesso.

No man could serve two masters with honour. If he did as Harif commanded, it would mean abandoning the Viscount at the hour of his greatest need. Yet every moment he stayed at Raymond-Roger’s side, he would be failing in his duty to the Noublesso.

Pelletier read the letter again, praying for a solution to present itself. This time, certain words, certain phrases stood out: ‘your brother awaits you in Besièrs.’

Harif could only mean Simeon. But in Béziers? Pelletier lifted the goblet to his lips and drank, tasting nothing. How strange that Simeon had come so forcefully into his mind today, after many years of absence.

A twist of fate? Coincidence? Pelletier believed in neither. Yet how to account for the dread that had swept through him when Alaïs had described the body of the man lying murdered in the waters of the Aude? There was no reason to imagine it would be Simeon, yet he’d been so certain.

And this: ‘your sister in Carcassona.’

Puzzled, Pelletier traced a pattern in the light surface of dust on the wooden table with his finger. A labyrinth.

Could Harif have appointed a woman as a guardian? Had she been here in Carcassonne, under his nose, all this time? He shook his head. It could not be.