HE SUBTERRANEAN space in which Mal’akh performed the Art was ingeniously hidden. His home’s basement, to those who entered, appeared quite normal—a typical cellar with boiler, fuse box, woodpile, and a hodgepodge of storage. This visible cellar, however, was only a portion of Mal’akh’s underground space. A sizable area had been walled off for his clandestine practices.

HE SUBTERRANEAN space in which Mal’akh performed the Art was ingeniously hidden. His home’s basement, to those who entered, appeared quite normal—a typical cellar with boiler, fuse box, woodpile, and a hodgepodge of storage. This visible cellar, however, was only a portion of Mal’akh’s underground space. A sizable area had been walled off for his clandestine practices.

Mal’akh’s private work space was a suite of small rooms, each with a specialized purpose. The area’s sole entrance was a steep ramp secretly accessible through his living room, making the area’s discovery virtually impossible.

Tonight, as Mal’akh descended the ramp, the tattooed sigils and signs on his flesh seemed to come alive in the cerulean glow of his basement’s specialized lighting. Moving into the bluish haze, he walked past several closed doors and headed directly for the largest room at the end of the corridor.

The “sanctum sanctorum,” as Mal’akh liked to call it, was a perfect twelve-foot square. Twelve are the signs of the zodiac. Twelve are the hours of the day. Twelve are the gates of heaven. In the center of the chamber was a stone table, a seven-by-seven square. Seven are the seals of Revelation. Seven are the steps of the Temple. Centered over the table hung a carefully calibrated light source that cycled through a spectrum of preordained colors, completing its cycle every six hours in accordance with the sacred Table of Planetary Hours. The hour of Yanor is blue. The hour of Nasnia is red. The hour of Salam is white.

Now was the hour of Caerra, meaning the light in the room had modulated to a soft purplish hue. Wearing only a silken loincloth wrapped around his buttocks and neutered sex organ, Mal’akh began his preparations.

He carefully combined the suffumigation chemicals that he would later ignite to sanctify the air. Then he folded the virgin silk robe that he would eventually don in place of his loincloth. And finally, he purified a flask of water for the anointing of his offering. When he was done, he placed all of these prepared ingredients on a side table.

Next he went to a shelf and retrieved a small ivory box, which he carried to the side table and placed with the other items. Although he was not yet ready to use it, he could not resist opening the lid and admiring this treasure.

The knife.

Inside the ivory box, nestled in a cradle of black velvet, shone the sacrificial knife that Mal’akh had been saving for tonight. He had purchased it for $1.6 million on the Middle Eastern antiquities black market last year.

The most famous knife in history.

Unimaginably old and believed lost, this precious blade was made of iron, attached to a bone handle. Over the ages, it had been in the possession of countless powerful individuals. In recent decades, however, it had disappeared, languishing in a secret private collection. Mal’akh had gone to enormous lengths to obtain it. The knife, he suspected, had not drawn blood for decades … possibly centuries. Tonight, this blade would again taste the power of the sacrifice for which it was honed.

Mal’akh gently lifted the knife from its cushioned compartment and reverently polished the blade with a silk cloth soaked in purified water. His skills had progressed greatly since his first rudimentary experiments in New York. The dark Art that Mal’akh practiced had been known by many names in many languages, but by any name, it was a precise science. This primeval technology had once held the key to the portals of power, but it had been banished long ago, relegated to the shadows of occultism and magic. Those few who still practiced this Art were considered madmen, but Mal’akh knew better. This is not work for those with dull faculties. The ancient dark Art, like modern science, was a discipline involving precise formulas, specific ingredients, and meticulous timing.

SIGILS OF DEMONS, FROM THE SOLOMONIC TRADITION

81.1: C.Walker/Topham/The Image Works

This Art was not the impotent black magic of today, often practiced halfheartedly by curious souls. This Art, like nuclear physics, had the potential to unleash enormous power. The warnings were dire: The unskilled practitioner runs the risk of being struck by a reflux current and destroyed.

Mal’akh finished admiring the sacred blade and turned his attention to a lone sheet of thick vellum lying on the table before him. He had made this vellum himself from the skin of a baby lamb. As was the protocol, the lamb was pure, having not yet reached sexual maturity. Beside the vellum was a quill pen he had made from the feather of a crow, a silver saucer, and three glimmering candles arranged around a solid-brass bowl. The bowl contained one inch of thick crimson liquid.

SIGNS OF THE ZODIAC

81.2: © iStockphoto.com/w-ings

The liquid was Peter Solomon’s blood.

Blood is the tincture of eternity.

Mal’akh picked up the quill pen, placed his left hand on the vellum, and dipping the quill tip in the blood, he carefully traced the outline of his open palm. When he was done, he added the five symbols of the Ancient Mysteries, one on each fingertip of the drawing.

The crown … to represent the king I shall become.

The star … to represent the heavens which have ordained my destiny.

The sun … to represent the illumination of my soul.

The lantern … to represent the feeble light of human understanding.

And the key … to represent the missing piece, that which tonight I shall at last possess.

Mal’akh completed his blood tracing and held up the vellum, admiring his work in the light of the three candles. He waited until the blood was dry and then folded the thick vellum three times. While chanting an ethereal ancient incantation, Mal’akh touched the vellum to the third candle, and it burst into flames. He set the flaming vellum on the silver saucer and let it burn. As it did, the carbon in the animal skin dissolved to a powdery black char. When the flame went out, Mal’akh carefully tapped the ashes into the brass bowl of blood. Then he stirred the mixture with the crow’s feather.

The liquid turned a deeper crimson, nearly black.

Holding the bowl in both palms, Mal’akh raised it over his head and gave thanks, intoning the blood eukharistos of the ancients. Then he carefully poured the blackened mixture into a glass vial and corked it. This would be the ink with which Mal’akh would inscribe the untattooed flesh atop his head and complete his masterpiece.

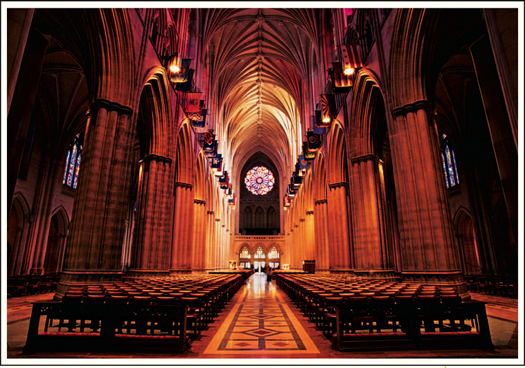

ASHINGTON NATIONAL Cathedral is the sixth-largest cathedral in the world and soars higher than a thirty-story skyscraper. Embellished with over two hundred stained-glass windows, a fifty-three-bell carillon, and a 10,647-pipe organ, this Gothic masterpiece can accommodate more than three thousand worshippers.

ASHINGTON NATIONAL Cathedral is the sixth-largest cathedral in the world and soars higher than a thirty-story skyscraper. Embellished with over two hundred stained-glass windows, a fifty-three-bell carillon, and a 10,647-pipe organ, this Gothic masterpiece can accommodate more than three thousand worshippers.

Tonight, however, the great cathedral was deserted.

Reverend Colin Galloway—dean of the cathedral—looked like he had been alive forever. Stooped and withered, he wore a simple black cassock and shuffled blindly ahead without a word. Langdon and Katherine followed in silence through the darkness of the four-hundred-foot-long nave’s central aisle, which was curved ever so slightly to the left to create a softening optical illusion. When they reached the Great Crossing, the dean guided them through the rood screen—the symbolic divider between the public area and the sanctuary beyond.

The scent of frankincense hung in the air of the chancel. This sacred space was dark, illuminated only by indirect reflections in the foliated vaults overhead. Flags of the fifty states hung above the quire, which was ornately appointed with several carved reredos depicting biblical events. Dean Galloway continued on, apparently knowing this walk by heart. For a moment, Langdon thought they were headed straight for the high altar, where the ten stones from Mount Sinai were embedded, but the old dean finally turned left and groped his way through a discreetly hidden door that led into an administrative annex.

They moved down a short hallway to an office door bearing a brass nameplate:

CENTER AISLE, WASHINGTON NATIONAL CATHEDRAL

82.1: Corbis Premium RF/Alamy

Galloway opened the door and turned on the lights, apparently accustomed to remembering this courtesy for his guests. He ushered them in and closed the door.

The dean’s office was small but elegant, with high bookshelves, a desk, a carved armoire, and a private bathroom. On the walls hung sixteenth-century tapestries and several religious paintings. The old dean motioned to the two leather chairs directly opposite his desk. Langdon sat with Katherine and felt grateful finally to set his heavy shoulder bag on the floor at his feet.

Sanctuary and answers, Langdon thought, settling into the comfortable chair.

The aged man shuffled around behind his desk and eased himself down into his high-backed chair. Then, with a weary sigh, he raised his head, staring blankly out at them through clouded eyes. When he spoke, his voice was unexpectedly clear and strong.

“I realize we have never met,” the old man said, “and yet I feel I know you both.” He took out a handkerchief and dabbed his mouth. “Professor Langdon, I am familiar with your writings, including the clever piece you did on the symbolism of this cathedral. And, Ms. Solomon, your brother, Peter, and I have been Masonic brothers for many years now.”

“Peter is in terrible trouble,” Katherine said.

“So I have been told.” The old man sighed. “And I will do everything in my power to help you.”

Langdon saw no Masonic ring on the dean’s finger, and yet he knew many Masons, especially those within the clergy, chose not to advertise their affiliation.

As they began to talk, it became clear that Dean Galloway already knew some of the night’s events from Warren Bellamy’s phone message. As Langdon and Katherine filled him in on the rest, the dean looked more and more troubled.

“And this man who has taken our beloved Peter,” the dean said, “he is insisting you decipher the pyramid in exchange for Peter’s life?”

“Yes,” Langdon said. “He thinks it’s a map that will lead him to the hiding place of the Ancient Mysteries.”

The dean turned his eerie, opaque eyes toward Langdon. “My ears tell me you do not believe in such things.”

Langdon did not want to waste time going down this road. “It doesn’t matter what I believe. We need to help Peter. Unfortunately, when we deciphered the pyramid, it pointed nowhere.”

The old man sat straighter. “You’ve deciphered the pyramid?”

Katherine interceded now, quickly explaining that despite Bellamy’s warnings and her brother’s request that Langdon not unwrap the package, she had done so, feeling her first priority was to help her brother however she could. She told the dean about the golden capstone, Albrecht Dürer’s magic square, and how it decrypted the sixteen-letter Masonic cipher into the phrase Jeova Sanctus Unus.

“That’s all it says?” the dean asked. “One True God?”

“Yes, sir,” Langdon replied. “Apparently the pyramid is more of a metaphorical map than a geographic one.”

The dean held out his hands. “Let me feel it.”

Langdon unzipped his bag and pulled out the pyramid, which he carefully hoisted up on the desk, setting it directly in front of the reverend.

Langdon and Katherine watched as the old man’s frail hands examined every inch of the stone—the engraved side, the smooth base, and the truncated top. When he was finished, he held out his hands again. “And the capstone?”

Langdon retrieved the small stone box, set it on the desk, and opened the lid. Then he removed the capstone and placed it into the old man’s waiting hands. The dean performed a similar examination, feeling every inch, pausing on the capstone’s engraving, apparently having some trouble reading the small, elegantly inscribed text.

“ ‘The secret hides within The Order,’ ” Langdon offered. “And the words the and order are capitalized.”

The old man’s face was expressionless as he positioned the capstone on top of the pyramid and aligned it by sense of touch. He seemed to pause a moment, as if in prayer, and reverently ran his palms over the complete pyramid several times. Then he reached out and located the cube-shaped box, taking it in his hands, feeling it carefully, his fingers probing inside and out.

When he was done, he set down the box and leaned back in his chair. “So tell me,” he demanded, his voice suddenly stern. “Why have you come to me?”

The question took Langdon off guard. “We came, sir, because you told us to. And Mr. Bellamy said we should trust you.”

“And yet you did not trust him?”

“I’m sorry?”

The dean’s white eyes stared directly through Langdon. “The package containing the capstone was sealed. Mr. Bellamy told you not to open it, and yet you did. In addition, Peter Solomon himself told you not to open it. And yet you did.”

“Sir,” Katherine intervened, “we were trying to help my brother. The man who has him demanded we decipher—”

“I can appreciate that,” the dean declared, “and yet what have you achieved by opening the package? Nothing. Peter’s captor is looking for a location, and he will not be satisfied with the answer of Jeova Sanctus Unus.“

“I agree,” Langdon said, “but unfortunately that’s all the pyramid says. As I mentioned, the map seems to be more figurative than—”

“You’re mistaken, Professor,” the dean said. “The Masonic Pyramid is a real map. It points to a real location. You do not understand that, because you have not yet deciphered the pyramid fully. Not even close.”

Langdon and Katherine exchanged startled looks.

The dean laid his hands back on the pyramid, almost caressing it. “This map, like the Ancient Mysteries themselves, has many layers of meaning. Its true secret remains veiled from you.”

“Dean Galloway,” Langdon said, “we’ve been over every inch of the pyramid and capstone, and there’s nothing else to see.”

“Not in its current state, no. But objects change.”

“Sir?”

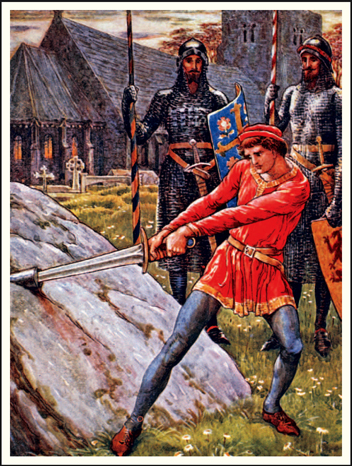

“Professor, as you know, the promise of this pyramid is one of miraculous transformative power. Legend holds that this pyramid can change its shape … alter its physical form to reveal its secrets. Like the famed stone that released Excalibur into the hands of King Arthur, the Masonic Pyramid can transform itself if it so chooses … and reveal its secret to the worthy.”

ARTHUR WITHDRAWING EXCALIBUR FROM THE STONE, WALTER CRANE

82.2: The Stapleton Collection/Art Resource, NY

Langdon now sensed that the old man’s advanced years had perhaps robbed him of his faculties. “I’m sorry, sir. Are you saying this pyramid can undergo a literal physical transformation?”

“Professor, if I were to reach out with my hand and transform this pyramid right before your eyes, would you believe what you had witnessed?”

Langdon had no idea how to respond. “I suppose I would have no choice.”

“Very well, then. In a moment, I shall do exactly that.” He dabbed his mouth again. “Let me remind you that there was an era when even the brightest minds perceived the earth as flat. For if the earth were round, then surely the oceans would spill off. Imagine how they would have mocked you if you proclaimed, ‘Not only is the world a sphere, but there is an invisible, mystical force that holds everything to its surface’!”

“There’s a difference,” Langdon said, “between the existence of gravity … and the ability to transform objects with a touch of your hand.”

“Is there? Is it not possible that we are still living in the Dark Ages, still mocking the suggestion of ‘mystical’ forces that we cannot see or comprehend? History, if it has taught us anything at all, has taught us that the strange ideas we deride today will one day be our celebrated truths. I claim I can transform this pyramid with a touch of my finger, and you question my sanity. I would expect more from an historian. History is replete with great minds who have all proclaimed the same thing … great minds who have all insisted that man possesses mystical abilities of which he is unaware.”

Langdon knew the dean was correct. The famous Hermetic aphorism—Know ye not that ye are gods?—was one of the pillars of the Ancient Mysteries. As above, so below … Man created in God’s image … Apotheosis. This persistent message of man’s own divinity—of his hidden potential—was the recurring theme in the ancient texts of countless traditions. Even the Holy Bible cried out in Psalms 82:6: Ye are gods!

“Professor,” the old man said, “I realize that you, like many educated people, live trapped between worlds—one foot in the spiritual, one foot in the physical. Your heart yearns to believe … but your intellect refuses to permit it. As an academic, you would be wise to learn from the great minds of history.” He paused and cleared his throat. “If I’m remembering correctly, one of the greatest minds ever to live proclaimed: ‘That which is impenetrable to us really exists. Behind the secrets of nature remains something subtle, intangible, and inexplicable. Veneration for this force beyond anything that we can comprehend is my religion.’ ”

“Who said that?” Langdon said. “Gandhi?”

“No,” Katherine interjected. “Albert Einstein.”

Katherine Solomon had read every word Einstein had ever written and was struck by his profound respect for the mystical, as well as his predictions that the masses would one day feel the same. The religion of the future, Einstein had predicted, will be a cosmic religion. It will transcend personal God and avoid dogma and theology.

Robert Langdon appeared to be struggling with the idea. Katherine could sense his rising frustration with the old Episcopal priest, and she understood. After all, they had traveled here for answers, and they had found instead a blind man who claimed he could transform objects with a touch of his hands. Even so, the old man’s overt passion for mystical forces reminded Katherine of her brother.

“Father Galloway,” Katherine said, “Peter is in trouble. The CIA is chasing us. And Warren Bellamy sent us to you for help. I don’t know what this pyramid says or where it points, but if deciphering it means that we can help Peter, we need to do that. Mr. Bellamy may have preferred to sacrifice my brother’s life to hide this pyramid, but my family has experienced nothing but pain because of it. Whatever secret it may hold, it ends tonight.”

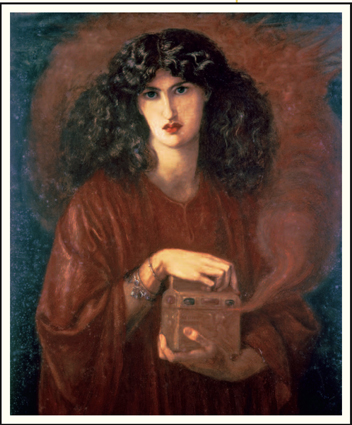

“You are correct,” the old man replied, his tone dire. “It will all end tonight. You’ve guaranteed that.” He sighed. “Ms. Solomon, when you broke the seal on that box, you set in motion a series of events from which there will be no return. There are forces at work tonight that you do not yet comprehend. There is no turning back.”

Katherine stared dumbfounded at the reverend. There was something apocalyptic about his tone, as if he were referring to the Seven Seals of Revelation or Pandora’s box.

PANDORA, DANTE CHARLES GABRIEL ROSSETTI

82.3: Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library

“Respectfully, sir,” Langdon interceded, “I can’t imagine how a stone pyramid could set in motion anything at all.”

“Of course you can’t, Professor.” The old man stared blindly through him. “You do not yet have eyes to see.”