By 9:30 P.M. the PT boats had reached their respective patrolling stations without incident. It was a moonless, starless night, so dark that it was hard to tell where the water ended and the sky began. At around midnight the Japanese destroyers passed through the strait, and some minor skirmishing occurred involving a few PTs, whereupon the destroyers continued on their way. Poor communication among the PTs meant that several of the boats without radar, including Kennedy’s 109, did not know what had occurred. The 159 and the 157, having fired their torpedoes, left the scene, leaving Kennedy’s boat as well as Lieutenant John Lowrey’s 162 behind. The two skippers stayed put, patrolling at idling speed and straining their eyes in the darkness looking for ships they didn’t know had already passed through. To conserve fuel and reduce the size of their wake so it wouldn’t be spotted by enemy boats or aircraft, Kennedy and Lowrey throttled down, operating on only one of three engines. A third boat, the 169, under the command of Lieutenant Phil Potter, emerged out of the blackness to join them. He, too, throttled down. The three boats now formed a picket line as they continued their slow patrol. Unbeknownst to them, the Japanese convoy had already discharged their cargoes and were now on the way back up the strait.30

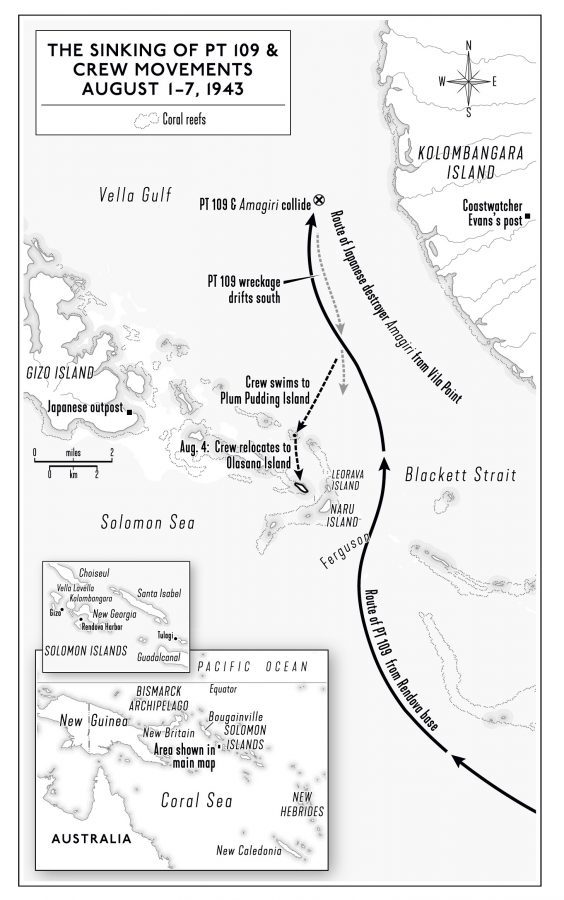

At 2:27 A.M., a silhouette suddenly appeared out of the darkness off Kennedy’s starboard bow, some two to three hundred yards away. Must be another PT boat that will soon veer off, the men thought. So did the crews on the 162 and the 169, who spotted the vessel at about the same time. But it kept coming, and suddenly everyone on the 109 understood what was happening: a Japanese destroyer was bearing down on them, like some charging skyscraper. Kennedy turned the wheel, but it was too late—with only his center engine in gear, he had no hope of maneuvering out of harm’s way, or of firing his torpedoes. Maguire grabbed his Miraculous Medal and had just begun to say, “Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us,” when the Amagiri sliced into the starboard bow of the 109 at a twenty-degree angle, shearing off a portion of the boat, then moved on into the night.31

“This is how it feels to be killed,” Kennedy thought to himself as he was thrown onto the deck.32 Two of his men—Machinist’s Mate Harold Marney, who was in the forward turret, and Torpedoman Andrew Kirksey, who had had strong premonitions of death in the days prior—perished more or less instantly; their bodies were never found. But Jack and ten others on the boat miraculously survived, most of them floating amid the debris and burning fuel, some of them barely conscious. Fortunately for them, the Amagiri’s churning wake had sucked most of the flames away from the wreckage, even as it cast the entire scene in a phantasmagoric light. Half of the wrecked boat stayed afloat, and one by one the men made their way over to it and climbed aboard. Machinist’s Mate Patrick McMahon, however, who had been belowdecks at the time of the collision and then had been carried some distance under the destroyer’s propellers, was too burned to make it on his own, so Kennedy dove back in and towed him back to the boat, a laborious task that took the better part of an hour. He also hauled in Gunner’s Mate Bucky Harris, who’d badly hurt his leg and could barely swim. (“For a man from Boston, you’re certainly putting up a great exhibition out here, Harris,” Kennedy said. Harris told him to go to hell.) Maguire, meanwhile, rescued Machinist’s Mate Gerard Zinser, and Lennie Thom hauled in William Johnston, another machinist’s mate who had inhaled gasoline fumes and could hardly move.33

The cacophony subsided and stillness returned. With eleven of the thirteen men accounted for and on board, the men of the 109 set about waiting. They knew the wreckage would not stay afloat forever. Initially, they expected either an enemy vessel or the other PTs to happen upon them, but no boats appeared. In the seconds before the collision, Lowrey’s 162 had tried to attack the Amagiri, but the torpedoes didn’t fire and Lowrey turned away to the southwest. Immediately after the ramming, the 169 fired two torpedoes that missed their target, whereupon Potter moved out of the vicinity. The two skippers would later say they thought the crew of the 109 had been killed in the collision or the flames, so there would be no point in sticking around in these dangerous waters, with more enemy destroyers perhaps coming through.

Some hours passed. “As dawn came up,” one crewman recalled, “we found ourselves on the boat with the boat under water all the way up to the bow. There was about 15 feet of the boat, which was 80 feet long, still sticking out of the water at a 45 degree angle, right side up.”34 They were deep in hostile territory, with Kolombangara to the east, Vella Lavella to the northwest, and the Gizo anchorage to the west-southwest. All were enemy-held, and the airstrip on Gizo was close enough that Kennedy and his men could see Japanese Zekes and Zeros taking off and landing.

As the morning progressed, the PT took on more water and began to turn her keel; soon she would disappear altogether in the dark blue waters. Jack asked the men for their suggestions on what to do—“There’s nothing in the book about a situation like this,” he said—and they made clear that the decision was his. He determined that they would swim to a coral island that could just be made out on the horizon some miles away, east of Gizo. He guessed that the island was too small to be enemy-held, but he could not be sure. Nor could he know if sharks were lurking nearby. They would have to chance it. Kennedy ordered the most severely hurt crew members and the poorest swimmers to hold on to a two-by-eight-foot plank (which had been part of the 37-millimeter gun mount) from which they would paddle along while he towed the ailing McMahon, holding the strap of the engineer’s life jacket in his teeth.35

“Will we ever get out of this?” someone asked.

“It can be done,” Kennedy replied. “We’ll do it.”36

Thus began an epic swim across Blackett Strait—in broad daylight, with the enemy close at hand. Four hours it would last. Jack would do the breaststroke for ten or fifteen minutes, rest a little while, then resume swimming, all the while reassuring McMahon and the other men that they were getting closer to their destination. Near sundown they finally made it, reaching the sandy beach of their precious refuge, Plum Pudding Island (known to locals as Kasolo), which turned out to be not much bigger than a football field and was partly covered in brush. There were coconuts in a handful of trees, but none within reach. A quick scan confirmed Jack’s hunch: no Japanese in sight. Utterly exhausted, he lay panting, his feet in the water and his head in the sand. His back throbbed. When at last he stood up, he vomited, on account of all the salt water he had swallowed. Gradually, he and McMahon made their way up the beach and collapsed under a bush as the others neared the island on their plank.37

Back at Tulagi and Rendova, meanwhile, word had spread rapidly about the ramming of the 109. The boat had exploded and been totally consumed by fire, reports indicated, and all men aboard were assumed dead. Preparations were made for a memorial service. Paul “Red” Fay, a spry and convivial PT officer who had met Jack briefly at Melville and later became a good friend—and would serve as undersecretary of the Navy in the Kennedy administration—despaired at the news, especially as his close pal George “Barney” Ross was on board. Fay wrote his sister, “George Ross lost his life for a cause he believed in stronger than any one of us, because he was an idealist in the purest sense. Jack Kennedy, the Ambassador’s son, was on the same boat and also lost his life. The man that said the cream of a nation is lost in war can never be accused of making an overstatement of a very cruel fact.”38

On his tiny island, Kennedy now had to calculate the odds of being rescued by Allied forces versus being found by the enemy. A Japanese barge floated by close to the shoreline; the men hid as best they could and breathed a sigh of relief when the vessel continued gently on its way. Next time they might not be so lucky. Time was also a factor, with McMahon in bad shape and several of the others, notably William Johnston, also suffering. With friendly boats unlikely to come into this part of Blackett Strait, Kennedy determined that, come evening, he would swim alone into Ferguson Passage, one of the approaches into the strait, in the hope of signaling a PT boat out on patrol. His usual approach in his young life—letting events come to him, being the detached if often perspicacious observer—would not suffice here, he realized. He had to seize control, had to bend destiny to his will. It was a brave idea, and a long shot. Even if an Allied skipper somehow spotted the lone light flashing in the darkness, would he really take his craft over to investigate? And if he did, who’s to say he or an overeager crew member wouldn’t shoot first and ask questions later? Kennedy acknowledged the odds against him, but he had no better idea, and doing nothing was tantamount to suicide. The men agreed, or at least offered no resistance.39

As darkness fell, Kennedy stripped down to his underwear, grabbed the battle lantern, and went on his way. To protect his feet from the coral, he wore shoes. On a lanyard around his neck hung his .38 revolver.

The eeriness of that night would stay with him always. Exotic creatures flitted about near him in the water, and he worried about the presence of sharks and barracuda. Much of the time, not a sound could be heard other than his own breathing and swim strokes. He was alone in the world. For a time he could rest, standing in waist-deep water on the barrier reef. As the hours went by, Kennedy realized there would be no rescue that night—by the flares in the far distance he could see that the PTs were patrolling elsewhere. He turned to swim back to his men, making steady progress until suddenly the current began taking him sideways. He fought it as best he could, swimming harder and ditching his shoes, but fatigue overtook him and he surrendered to the tide, to the immensity, to the blackness. He drifted, clutching his lantern, not sure whether he would live or die, until in the predawn hours he found himself near the tiny islet of Leorava. He straggled onto the beach, his feet bleeding from the coral, his back aching, and promptly fell asleep. Upon waking shortly after dawn, he swam the half mile back to Plum Pudding Island, collapsing in exhaustion as soon as he laid eyes on Lennie Thom and Barney Ross.40

That evening Ross took his turn swimming out into the strait; again, no friendly boat appeared. Hunger was now a major concern, and thirst even more so, so Jack decided the group would take to the water again, bound for Olasana Island, a slightly larger atoll to the south. The journey, on the morning of August 4, took close to three hours against a strong current, Jack again towing McMahon by a strap between his teeth, and it proved a wise move: Olasana had coconuts, in the trees and on the ground, that provided crucial sustenance. But rescue seemed as far away as ever, so on the following day Kennedy and Ross set out once more, swimming to a still larger island, Naru (also known as Cross Island), directly on Ferguson Passage. Here they happened upon a damaged one-man canoe as well as small bags of Japanese candy and crackers and a drum of potable rainwater. They also spotted, some distance away, what appeared to be two native islanders in a canoe. Kennedy and Ross waved at them to stop, but the men, afraid that they were Japanese, paddled frantically away.41

When Kennedy returned to Olasana late that night (Ross had stayed behind on Naru), he was astonished to see the same two locals there, communing with the men of PT 109. Their names were Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana, and they were teenage scouts working for the Allies. A new excitement gripped the Americans: could this be the break they needed? Kennedy persuaded Biuku to paddle him back to Naru for another attempt at flagging down a friendly boat in Ferguson Passage. The effort failed, but, at Biuku’s suggestion, Jack scrawled a now famous message on the husk of a coconut: NAURO ISL COMMANDER NATIVE KNOWS POSIT HE CAN PILOT 11 ALIVE NEED SMALL BOAT KENNEDY. Biuku and Eroni took the coconut, along with a handwritten note by Thom, and made for the Rendova base, some thirty-eight miles away, through dangerous waters. En route, the two men stopped off at a nearby island to inform a fellow scout of the news; he in turn informed an Australian coastwatcher (an intelligence operative who observed enemy ship and troop movements, and also helped rescue stranded Allied personnel), Lieutenant A. Reginald Evans, who promptly dispatched seven of his scouts to Olasana in a large canoe laden with food, drink, and cigarettes.42

The scouts carried a message for Kennedy: “I strongly advise that you come with these natives to me. Meanwhile, I shall be in radio communication with your authorities at Rendova and we can finalize plans to collect the balance of your party.”43 The following day, Saturday, August 7, the islanders brought Jack, who was hidden under ferns in the boat, to the Australian’s camp. From there, things moved rapidly. The brass at Rendova, fearing it could be a trap to lure American forces into an ambush, allotted only one boat to the rescue attempt, William “Bud” Liebenow’s PT 157, which got to the scene without incident.

“Where the hell you been?” Kennedy shouted when the boat picked him up en route to Olasana, shortly after 11 P.M.

“We got some food for you,” Liebenow called back.

“No, thanks,” Kennedy answered. “I just had a coconut.”44

Soon all eleven men were aboard PT 157 and on their way to Rendova for medical attention, arriving there at 5:30 A.M. on August 8. Their ordeal was over, seven days after it began.