CHAPTER 29

As Meredith had suspected, the road was still shut. Her rental car was right where she’d left it, behind the blue Peugeot. A couple of other cars had joined them on the sidewalk.

She walked past the Jardin Paul Courrent and along the main street towards the lights, then turned right up a very steep road that seemed to run straight into the hillside itself. It led to a car park, which was surprisingly full given how empty the town seemed. She read the tourist information board, a rustic wooden sign advertising walks to local landmarks: L’Homme Mort, La Cabanasse, La Source de la Madeleine, and a cross-country route to a neighbouring village, Rennes-le-Château.

It wasn’t raining, but the air had gotten damp. Everything seemed muffled and subdued. Meredith went on, peering up alleyways that seemed to lead nowhere, glancing into the brightly lit windows of houses, then doubled back to the main street. Straight ahead was the Mairie, with the tricolore fluttering blue, white and red in the evening air. She turned left and found herself in the Place des Deux Rennes.

Meredith stood a while, taking in the atmosphere. There was a charming pizzeria on the right with wooden tables outside. Only a couple of the tables were occupied, both with groups of English people. On one, the men were talking football and Steve Reich, while the women – one with stylish cropped black hair, another with blond hair cut sharp to the shoulders, the third with auburn curls – were sharing a bottle of wine and discussing the latest Ian Rankin. On the second table was a crowd of students, eating pizza and drinking beer. One of the boys was wearing a blue studded leather jacket. Another was talking about Cuba to a darker haired friend, who had an unopened bottle of Pinot Grigio at his feet, and a slightly younger boy who was reading. The last member of the group, a pretty girl with streaks of pink in her hair, was making the shape of a square with her hands as if framing the scene for a photograph. Meredith smiled as she walked by, reminded of her own students. The girl noticed and smiled back.

In the far corner of the square, Meredith noticed a cloche-mur with a single bell above the rooftops of the buildings and realised she’d found the church.

She walked down a cobbled approach that led to l’église de Saint-Celse et Saint-Nazaire. A single overhead lamp was burning in the unassuming porch, open to the elements to north and south. There were two tables too, incongruous-looking and empty.

The sign on the parish noticeboard next to the door stated that the church was open from ten every morning through dusk, except for feast days and weddings and funerals. But when she tried the handle, it was locked even though lights were on inside.

She looked at her watch. Half after six. Maybe she’d just missed it.

Meredith turned around. On the opposite wall was a board of names, a roll call of the men of Rennes-les-Bains who’d given their lives in World War I.

A Ses Glorieux Morts.

Was death ever glorious, Meredith wondered, thinking of her sepia soldier? Of her birth mother walking into Lake Michigan with her pockets weighted down with stones. Was the sacrifice worth it?

She stepped forward and read down the alphabetical list of names right to the end, knowing that it was pointless to expect Martin to be there. It was crazy. From what little background Mary had been able to pass on, Meredith knew that Martin was Louisa’s mother’s surname, not her father’s. In fact, on her birth certificate it said FATHER UNKNOWN. But Meredith did know her ancestors had emigrated from France to America in the years after the First World War, and after the research she’d done, she was pretty certain the soldier in the photograph was Louisa’s father.

She just needed a name.

Something caught her eye. BOUSQUET was there on the memorial. Like the Tarot cards sitting in her bag in the trunk. Maybe the same family? Something else to check out. She moved on. At the bottom of the plaque, an unusual name: SAINT-LOUP.

Next to the board were a stone plaque in memory of Henri Boudet, Curé of the parish from 1872 to 1915, and a black metal cross. Meredith thought about it. If her unknown soldier had come from here, Henri Boudet might have known him. It was a small town after all and the dates were about right.

She copied it all down: first rule of research – and the second and third – write everything down. You never knew until later what might turn out to be relevant.

Beneath the cross were inscribed the Emperor Constantine’s famous words: ‘In hoc signo vinces’. Meredith had come across the phrase plenty of times before, although this time it set some other thought racing through her head. ‘By this sign shall you conquer,’ she murmured, trying to figure out what was bugging at her, but nothing came.

She walked through the porch, past the main door into the church, and out into the graveyard itself. Straight ahead there was another war memorial, the same names, with one or two additions and discrepancies of spelling, as if to mark their sacrifice only once would be too little.

Generations of men, fathers, brothers, sons, all those lives.

Meredith walked slowly in the sombre twilight down the gravelled path that ran alongside the church. Tombs, graves, stone angels and crosses loomed up at her as she passed. Every now and again she paused to read an inscription. Certain names repeated over, generation after generation of local families, remembered in granite and marble – Fromilhague and Saunière, Denarnaud and Gabignaud.

At the furthest boundary of the cemetery, overlooking the river gorge, Meredith found herself standing before an ornate mausoleum with the words FAMILLE LASCOMBE-BOUSQUET carved above the metal grille.

She crouched down and, in the last vestiges of daylight, read of the marriages and births that had united the Lascombe and Bousquet families in life and now in death. Guy Lascombe and his wife had been killed in October 1864. The last of the Lascombe line had been Jules, who died in January 1891. The final surviving member of the Bousquet branch of the family, Madeleine Bousquet, had passed on in 1955.

Meredith straightened up, aware of the familiar prickling feeling on the back of her neck. It wasn’t just the Tarot deck Laura had pressed on her and the coincidence of the Bousquet name, but something else. Something about the date, something she’d seen but not paid enough attention to at the time.

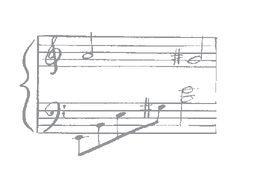

Then she got it. The year 1891 kept coming up, more than its fair share. She noticed that date in particular because of its personal significance. It was the date printed on the piece of music. She could see the title and the number in her mind’s eye as clearly as if she was holding it in her hand.

But there was something more. She ran back everything in her mind from the second she’d walked into the church-yard, until she figured it out. It wasn’t just the year so much as the fact that the same actual date kept repeating over.

With a burst of adrenalin, Meredith hurried back through the tombs, weaving in and out, checking the inscriptions, and found she was right. Her memory wasn’t playing tricks on her. She pulled out her notebook and started to scribble, recording the same date of death for different people, three, four times over.

All had died 31st October 1891.

Behind her, the tiny bell in the cloche–mur began to toll.

Meredith turned round and looked at the lights inside the church, then glanced up and saw that there were now stars dotted across the sky. She could hear voices too, a low murmuring. She heard the church door open, a rush of louder voices before it shut again with a clatter.

She retraced her steps back into the porch. The wooden trestle tables were now in use. One was covered in gifts – flowers in cellophane, bouquets, houseplants in terracotta pots. The second was laid with a thick red felt cloth with a large book of condolence set on it.

Meredith couldn’t resist taking a look. Beneath that day’s date was a name and dates of birth and death: SEYMOUR FREDERICK LAWRENCE: 15 SEPTEMBRE 1938- 24 SEPTEMBRE 2007.

She realised the funeral was about to begin, even though it was late. Not wanting to get caught up, she walked quickly back into the Place de Deux Rennes. The square was busy now. Thronging around, quiet but not silent, were people of all ages. Men in blazers, women in pressed pastels, kids in suits and smart dresses. What Mary would call Sunday best.

Standing in the shadow of the pizzeria, not wanting to look like she was rubber-necking, Meredith watched as the mourners disappeared into the presbytery next to the church for a few minutes, then emerged and went into the porch to sign the book of condolence. It seemed the whole town had turned out.

‘Do you know what’s going on?’ she asked the waitress.

‘Funérailles, Madame. Un bien-aimé.’

A lean, thin woman with short dark hair was leaning against the wall. She was standing perfectly still, but her eyes were darting around all over. When she lifted her hand to light her cigarette, the sleeves of her shirt slipped down and Meredith noticed thick red scars around both wrists.

As if sensing someone was looking, the woman turned her head and looked right at her.

‘Un bien-aimé?’ Meredith said, casting round for something to say.

‘Someone popular. Well-respected,’ the woman replied in English.

Of course. Pretty obvious.

‘Thanks.’ Meredith gave an embarrassed smile. ‘I wasn’t thinking.’

The woman kept staring a moment longer, then turned her head away. The bell began to toll more insistently, a thin and reedy sound. The crowd stood back as four men came out of the presbytery carrying a closed casket. Behind them, a young guy dressed in black, late twenties maybe, with a mop of brown hair. His face was white, his jaw rigid, as if struggling to keep control.

Beside him was an older man, also dressed in black. Meredith’s eyes widened. It was the driver of the blue Peugeot, looking totally in control. She felt a shot of guilt at her reaction earlier.

No surprise he was so abrupt.

Meredith watched as the coffin made its short journey from the presbytery to the church. The tourists at the café opposite got to their feet as the mourners filed past. The students stopped talking and stood in silence with their hands clasped in front of them as the slowly moving mass of people disappeared down the passageway.

The door of the church fell shut with a clatter. The bell stopped ringing, leaving only an echo in the evening air. Quickly, everything in the square returned to normal. The scrape of chair legs, people picking up glasses, napkins, lighting cigarettes.

Meredith noticed a car driving up the main street, heading south. Then several more. To her relief the road was open again. She wanted to get to the hotel.

She stepped out of the lee of the building and, finally, took in the whole vista rather than just one detail of it. Suddenly, she saw it. The photograph of the young soldier, her ancestor, had been taken here, the precise spot framed by the buildings leading to the Pont Vieux, between a line of platanes and the wooded hillside glimpsed through the gap in the houses.

Meredith dug into her purse, pulled out the envelope and held the image up.

An exact match.

The café signs and the bed and breakfast on the east side of the square were new, but otherwise it was the same view. Right here, in 1914, a young man had stood and smiled at the camera before going off to fight. Her great-great-grandfather, she was certain of it.

With renewed enthusiasm for the task she’d set herself, Meredith walked back to her car. She’d been here less than an hour and already she’d found something out. Something definite.