PREFACE

Early one morning in August 1939, twenty-two-year-old Jack Kennedy looked out his window at the Hotel Excelsior, in Berlin, not far from the Reich Chancellery, and caught a glimpse of things to come: on the street below, Nazi storm troopers marched by. A rising senior at Harvard, Kennedy was nearing the end of an extraordinary seven-month study-abroad adventure, one that had included stints working in the U.S. embassies in London (where his father was the ambassador) and Paris, as well as travels to a dozen countries in Europe and the Middle East. At each stop, he’d used his father’s connections to meet with local officials and U.S. diplomats, asking questions, taking notes, and forming a picture of a world in crisis.1

Now he was in Germany’s capital, the nerve center of Nazi power. Rumors were rife that Hitler’s armies were readying to invade Poland. Kennedy, a skeptic by nature, wasn’t sure—the German dictator might be bluffing—but he felt unease as he took in the atmosphere of tense expectancy in the city. At every turn, he saw evidence of fearsome Nazi propaganda at work as the authorities bombarded Berliners with supposed proof of heinous behavior by the contemptible Poles.2 So relentless was the barrage, Kennedy suggested in a letter to his friend Lem Billings on August 20, that German officials might be hemming themselves in, unable to back down even if they wanted to. Moreover, Jack wondered, did Hitler grasp that Britain and France, allied to Poland, were likely to show greater resolve this time than they had mustered during the Munich negotiations the previous year, when they had meekly let the Führer seize part of Czechoslovakia? “England seems firm this time,” he wrote to Billings, “but as that is not completely understood here the big danger here lies in the Germans counting on another Munich then finding themselves in a war when Chamberlain refuses to give in.”3

The following evening, shortly before midnight, came staggering news via Berlin radio: Germany and the Soviet Union, longtime bitter foes, would sign a nonaggression pact, with details to be worked out in Moscow in two days. Though many ordinary Germans were relieved—surely the Poles would now succumb without a fight, and the conflict would be resolved in much the same nonviolent way as the Czech crisis the previous year—seasoned diplomats, privy to official thinking in Warsaw and Paris and London, knew better.4 They recognized that the Nazi-Soviet deal, by isolating the Poles, made war more likely, not less. When Jack visited the U.S. embassy shortly before his departure from the city, Alexander Kirk, the chargé d’affaires and senior officer (Ambassador Hugh Wilson had departed several months prior), asked him to take a secret message back to Ambassador Kennedy in London: Germany would invade Poland within a week.5

The invasion came on September 1. By then Jack was back in London, joining his parents and eight siblings at the ambassadorial residence in Knightsbridge. On September 3, he and his mother, Rose, along with two of his siblings—older brother Joe Junior and younger sister Kick—were in the visitors’ gallery of the House of Commons when Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain somberly affirmed what he had just announced in a radio broadcast: Britain was at war with Germany. Jack’s worry as expressed to Lem Billings two weeks before had been borne out. Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, an unbending supporter of Chamberlain’s failed efforts to avert war through a policy of appeasement, had been moved almost to tears by the prime minister’s mournful radio address. His wife felt the same as she took in Chamberlain’s remarks in the Commons.6

For Jack, however, another speaker on this historic day left the deepest impression. Standing before the Commons as the incoming First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill summoned his compatriots to the glorious endeavor ahead: “Outside, the storms of war may blow and the lands may be lashed with the fury of its gales, but in our own hearts this Sunday morning there is peace.” Jack watched transfixed as Churchill declared, “Our hands may be active, but our consciences are at rest.”7

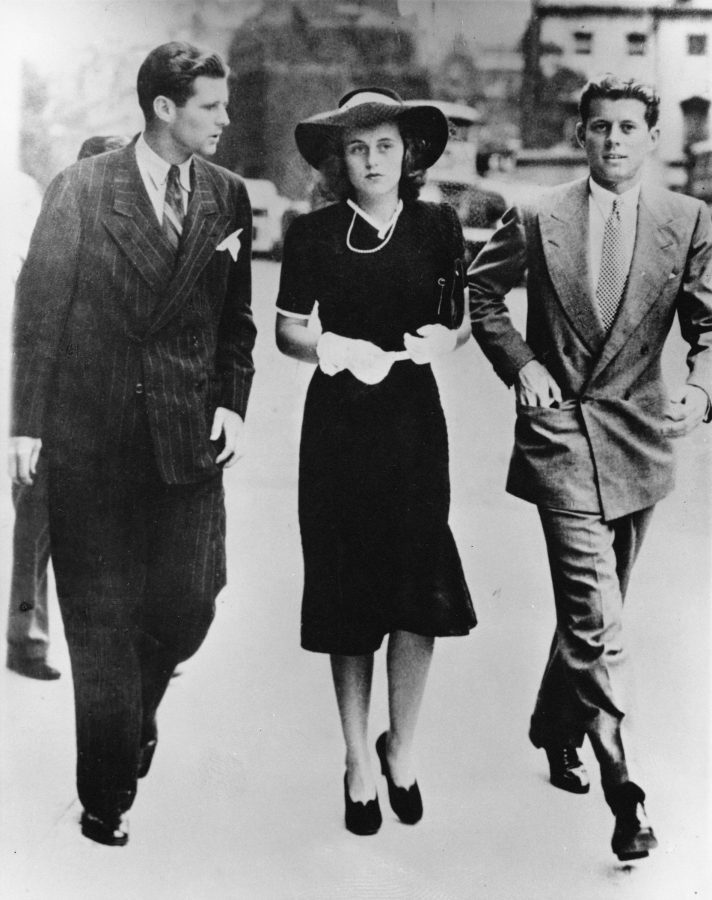

A photo shows the three Kennedy siblings—vibrant and handsome—on their way to the Houses of Parliament:

The trio understood that they were eyewitnesses to history. But they had no inkling of how much the war that was just beginning would transform the world and their place in it. In five years, Joe Junior would be erased from the picture, killed in action, and Kick’s husband would also perish, mere weeks after their wedding. Joe Senior’s public career would be destroyed. The war would also tear asunder the European-led international order, as Jack saw up close when he returned to the Continent in mid-1945 as a twenty-eight-year-old journalist and decorated veteran. Germany had capitulated, and its ally imperial Japan was ravaged, close to defeat. Much of Berlin, including the Excelsior, lay in ruins. Two Allied powers, the Soviet Union and the United States, stood supreme, eyeing each other warily as they began to fill the geopolitical vacuum left by the war. When Kennedy came back again in 1948, as a junior congressman, Kick, too, was gone, and the Soviets and Americans were locked in a tense Cold War, with Berlin a focal point. This superpower confrontation was still ongoing when now-President Kennedy returned yet again, in June 1963, and declared, before a rapturous audience of more than a million in West Berlin, “Ich bin ein Berliner.” Five months later, he met his death, felled by an assassin’s bullet while riding in an open-air limousine in Dallas.

World War II occupies a central place in this book, the first of two volumes on the life and times of John F. Kennedy. Born in 1917, during one world war and at the dawning of the American Century, he came of age in a second world war, then rose all the way to the presidency, only to be cut down at forty-six while leading a United States that stood at the zenith of its power. He was a man of privilege and wealth who endured chronic ill health and pain as well as immense personal tragedy, and whose storybook life captivated millions of people—not merely in the United States but abroad, not merely in death but in life. Known for his handsome looks, cool and graceful demeanor, and persistent womanizing, Kennedy was gifted and flawed, as a politician and as a person, and his thousand days in the White House saw missteps as well as successes. But through his magnetic leadership and inspirational rhetoric, he elevated Americans’ belief in the capacity of politics to solve big problems and speak to society’s highest aspirations, while in foreign affairs he showed it was possible to move from bitter hostility toward the Soviet Union to coexistence. The public responded. By the middle of 1963, close to 60 percent of Americans claimed that they had voted for Kennedy in 1960, although only 49.7 percent had actually done so. After his death, his landslide grew to 65 percent. Kennedy’s average approval rating of 70 percent while in office puts him at the top among post-1945 American presidents, and later generations would rate his performance higher still.8

Despite Kennedy’s larger-than-life status, few serious biographies of him have been attempted, and there exists virtually no full-scale biography, one that considers the full life and times and makes abundant use of the massive archival record now available—some of it only recently declassified.9 The White House period must of course loom large, and will take up the bulk of volume 2, but so, too, do Kennedy’s pre-presidential and pre-congressional years demand our attention.10 For Kennedy, as for most of us, his teens and twenties were the years when his personality and worldview took shape. His war experience, in particular, had a profound effect on his outlook and his career trajectory, informing a political philosophy he would carry with him always.11

There’s another reason why the early years of John Kennedy warrant close scrutiny. To a greater degree than with most public figures, the man known universally by his initials has been swept away by mythology. The JFK legend has obscured the real-life Kennedy, the workaday Kennedy, rendering him opaque and inscrutable. To recapture him, one must examine him when he was young and untried, still finding his way in his large and competitive Irish Catholic family and in the world, still learning what he was about. Within these pages, therefore, is a portrait of the full man—his relationships, his experiences, his ideas, his writings, his political aspirations. It’s an effort made easier by the vast correspondence the Kennedy family conducted from the start of the 1930s through World War II, much of which survives and is now open for research at the John F. Kennedy Library, in Boston.12 Kennedy himself was a prolific letter writer at key points in his life, and he kept diaries and notebooks during many of his travels. A number of his college papers survive, as does his senior thesis, which was published as a widely praised book, Why England Slept, in 1940, soon after his graduation and the fall of France, when he was only twenty-three.

Of course, any serious attempt to re-create Kennedy’s world as he experienced it requires suspending as much as possible the knowledge of how it all turned out, and resisting the urge to see in this freshman essay or that wartime letter seeds of his later greatness. Only by so doing can one hope to play it straight, to look the man right in the eye, not up in adulation or down in disdain.

No less important, the work of biography requires bearing in mind that Kennedy was a product of his time and place. Context matters—a lot. And there’s a payoff here, indeed a double payoff: situating Kennedy within the wider setting of the era and the world helps us better comprehend not only his rise but his country’s rise, first to great-power status and then to superpower status. In fact, a principal theme of this book is the degree to which Kennedy’s life story tracks with major facets of America’s political and geopolitical story. The charged debate between “isolationists” and “interventionists” in the years before Pearl Harbor; the tumult of the Second World War, through which the United States emerged as a global colossus; the outbreak and spread of the Cold War; the domestic politics of anti-Communism and the attendant scourge of McCarthyism; the growth of television’s influence on politics—each of these seminal events and developments can be grasped more clearly through the lens of John F. Kennedy’s life and career. The same holds for the period to be examined in the volume still to come, when additional topics come to the fore: civil rights; the arms race and the prospect of nuclear Armageddon, made vivid during the tense days of the Cuban Missile Crisis; the revival of affirmative government as a precursor to the Great Society; the descent into Vietnam (for which Kennedy, despite his early and prescient misgivings about seeking a military solution there, would bear considerable responsibility); and the space program.

The more we understand Kennedy and his coming of age, in short, the more we understand the United States in the middle decades of the century. I am struck in this regard by historian and Kennedy adviser Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.’s remark, in his memoirs, A Life in the 20th Century: “For my generation, four dates remain indelibly scarred on memory, four occasions when none of us can forget where and how we heard the staggering news: Pearl Harbor, the death of Franklin Roosevelt, the death of John Kennedy, the landing of men on the moon.”13 All four moments are, in their way, pivotal to the story I’m telling here. Though Kennedy did not live to see the moon landing, his initial commitment to the lunar project made it happen.

A second theme, captured in the image of the college-age Kennedy crisscrossing Europe and the Middle East in the lead-up to World War II, concerns his pronounced international sensibility. He was, from the start, a man of the world, deeply inquisitive about other political systems and cultures, comfortable with competing conceptions of national interest. This was partly an outgrowth of his Irish heritage and the sensibility of his parents, and in particular his mother, who looked outward, beyond the nation’s shores. Partly, too, it resulted from his expansive reading as a bedridden child and teenager, which tilted toward European history and statecraft, and from his coursework in prep school and college. Most of all, the internationalist ethos emerged from Kennedy’s travels during and after his college years—in addition to his grand excursion in 1939, there were substantial trips in 1937, 1938, and 1941. These trips broadened his horizons, as did his subsequent combat experience in the South Pacific. An interventionist well in advance of Pearl Harbor—in contrast to his father and older brother, who argued until the Japanese attack for keeping America out of the struggle, whatever the cost—Jack came out of the war committed to the proposition that the United States must play an ongoing leadership role in world affairs, working in concert with other nations. Thereafter, he held firmly to this view.

Herein lies a third theme: on matters of politics and policy, JFK was always his own master. His father, deeply influential in the lives of his children, was a towering figure in young Jack’s life, modeling how he expected his second son to behave, not least in his brazen philandering. But there was always the sense that Jack stood somewhat apart from his large and close-knit family—he was of the unit but also outside of it. He was the family reader, the daydreamer, the introspective son, the one who relished words and their meaning, who liked poetry. Alone among the older kids, he had a romantic imagination, a feel for the things of the spirit, for the intangibles in human affairs. (It’s what drew him to Churchill, a man whose appeal Joe Senior could never grasp.)14 For years Jack resisted his father’s exhortations to work harder in school, to apply himself; when he finally buckled down, in his junior year at Harvard, it was for his own reasons. Whereas Joe Junior always parroted his father’s views on policy matters, Jack broke with the patriarch at key junctures, especially in the realm of foreign policy. He saw a more complex and crowded world than did the older man, and Why England Slept was partly a rebuke of Joe Senior’s isolationist position. Later, in the early stages of the Cold War, Jack embraced a strident anti-Soviet position that his father loudly rejected. On domestic policy, Congressman and then Senator Kennedy was consistently to Joe Senior’s left, though still a centrist within the Democratic Party as a whole.

Nor does the evidence support the claim, common in books as well as documentary films, that Jack Kennedy became a politician because his father decreed it, following the death of Joe Junior, his golden firstborn, in 1944. In reality, Jack was musing about seeking elected office at least two years earlier, in early 1942. His boyhood had been imbued by the political legend of his beloved grandfather John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, and he relished hearing stories about the feats and foibles of earlier generations of Irish Catholic pols in Boston. In college he gravitated toward the study of government, and a later flirtation with law school was in part a manifestation of his deep interest in politics. No doubt the father’s relentless advocacy after Joe’s death was an additional spur, and it’s interesting to speculate about which path Jack might have selected had his brother returned from the war alive. But he had his own reasons for choosing politics, and of the two brothers he could arguably claim the stronger credentials for the endeavor—as Joe Junior grasped all too well. During Jack’s initial campaigns for the House (in 1946) and the Senate (in 1952), Joe Senior played an important role, not least in keeping his checkbook open at all times. Contrary to legend, however, he never drove campaign strategy, in either race. The son, never much impressed with his father’s political acumen, preserved the key decision-making slot for himself. In the epic 1952 nail-biter against Republican Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., the paramount subordinate family part was played not by Joe Senior but by Jack’s twenty-six-year-old brother, Robert.

Ultimately, the Kennedy who emerges in these pages is not the callow young man of our imaginations. At least not in the main, and at least not after he graduated from college. He could be vain and self-centered, could be heedless of friends, heedless of women. He cheated on his wife, Jackie, before their wedding, and he cheated on her afterwards. To him, as to others in his wealthy family, people were often viewed as interchangeable. (Which did not keep him from showing deep loyalty to a chosen few—namely, to his male friends and to his core staff, who repaid the loyalty in full.)15 But that was not the sum total of the man. Behind the handsome face and the winsome smile was an insatiably curious individual, a poised and discerning analyst who treated serious things seriously yet largely avoided—thanks to his highly developed sense of irony and the absurd, and his self-deprecating wit—the trap of self-importance.16 His historical sensibility and his recurring health travails taught him that life was capricious and fraught, but he didn’t take from this that he should use his family’s fortune to pursue a path of pure indulgence. On the contrary, these hardships deepened his determination to follow his parents’ exhortation, issued regularly to their kids, to contribute to society, to believe in something greater than themselves and to act accordingly.

Signs of this emerging seriousness were evident early; he was no late bloomer, as is often suggested. Already in his undergraduate papers, Kennedy grappled with questions concerning political leadership that would fascinate and vex him to the end of his days. Is it possible for democratic leaders to respond nimbly and effectively in times of national or international crisis? How can policymakers reconcile their sense of the nation’s interests with the fickle demands of their constituents? What is the nature of political courage? (“Unless democracy can produce able leaders,” he wrote in one college essay, “its chances of survival are slight.”) In letters home from the South Pacific in 1943, he expressed doubts about the efficacy of military leadership and about war as an instrument of policy that would deepen in the years ahead. “The war here is a dirty business,” he wrote to his ex-girlfriend Inga Arvad. “We get so used to talking about billions of dollars and millions of soldiers, and thousands of casualties begin to sound like drops in the bucket. But if those thousands want to live as much as my PT boat crew, the people deciding the whys and wherefores had better make mighty sure that all this effort is headed for some definite goal and that when we reach that goal we may say it was worth it.” In late 1951, following two lengthy overseas trips covering much of the world, he revised his easy Cold War verities and told a nationwide radio audience that the Communist threat “cannot be met effectively by merely the force of arms. It is the peoples themselves that must be led to reject it, and it is to those peoples that our policies must be directed.” Democratic ideals, he was saying, mattered more than military power. This, too, was a theme to which he would return often, including as president.17

Even that most celebrated of Kennedy appeals, “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country,” from the 1961 inaugural, had early roots. It had been drilled into him at Choate, his prep school alma mater. When, in 1946, he returned to the school to give an address, he urged the students to be engaged citizens and to answer the call to public service.18 On the stump that year, in his first election campaign, he elaborated the argument, sounding tones that seem especially resonant in our own time. Beware lazy cynicism about politics and politicians, the skinny twenty-nine-year-old candidate implored audiences, for the survival of democracy depended on having an informed and active citizenry, committed to reasoned discourse and accepting of good-faith bargaining between the parties. He employed the language of empathy, emphasizing Americans’ shared dreams and shared destiny as a people. Neither then nor later was Kennedy above bare-knuckle politics or partisan sparring, but he grasped already in this first race that compromise is necessary to a well-functioning democracy, and that civility in the public realm prevents dehumanization and helps us see political opponents as adversaries, not enemies. His 1956 book, Profiles in Courage, is an ode to the art of politics, to the hard and vital work of governing in a system of conflicting pressures and visions.

Perhaps it’s this abiding faith in his nation and its democratic politics that explains most fully the enduring hold of John F. Kennedy’s legacy. From his earliest days as a politician right to the end in Texas, Kennedy summoned the narrative of American hope as he challenged people to believe in a better society at home while embracing the nation’s leadership position abroad. It was a capacious vision, one that rejected the parochial nationalism of his father and extolled the promise of public activism. Today, whether we question this governing philosophy or yearn for its rebirth, we still see Kennedy as the dynamic young figure who seized the mantle of leadership, and we wonder what might have been had he lived.19 We’ll never know, no matter how much we imagine. But we can learn much about this singular and surprising life, and about the nation and the world in which he came of age, if we delve deeply into who he really was.