IV

With a live-in staff that freed her from some of the basic caregiving for the younger children, Rose could focus her attention on the intellectual and social development of the older ones. In addition to outings to points of interest in Brookline, including the public library on Washington Street, she took them on regular visits to see Boston’s historic sites, much as Honey Fitz had done with her when she was little. (Often she would rattle off improvised math challenges en route: “What is two plus two, subtract three, then add two?”) Rose was adamant that “they should know history and especially the history of their own country,” and on their excursions to landmarks she would explain what had happened at the spot and why it mattered, encouraging questions and discussion so the kids would remember. “I was determined about this, and I may have overdone it a little since there can be too much even of a good thing,” she recalled. “In any case they did learn, their interest developed with the years, and I suspect that this may be one reason why as adults they wanted to serve the country in public life.”44

Jack in particular seemed to be fascinated by history, and by the world generally. His curiosity was insatiable. Rose noticed it during these day trips, and also when she read to him in the evenings. He loved adventure stories of all kinds—Sinbad the Sailor, Black Beauty, Peter Pan—and was especially fond of Billy Whiskers, a picture book series by Frances Trego Montgomery featuring a mischievous goat that marries and has two “kids.” Rose found the illustrations crude and harsh, but Jack adored the tales. When he learned in one story that Billy stopped in the Sandwich Islands on his way across the Pacific, Jack asked his mother to get information on this mysterious-sounding place, which she duly did, pulling out the family atlas so Jack could see for himself. Another time, when she read to the older children the Easter story of Christ’s entrance into Jerusalem on a donkey, shortly before the Crucifixion and Resurrection, Jack piped up: “Mother, we know what happened to Jesus Christ, but what happened to the donkey?”45

With his quick wit and irreverent spirit, Jack resembled his maternal grandfather, Honey Fitz, which may explain why the two got on so well. A frequent visitor in these years, “Grandpa Fitz” would take the two older boys for hours at a time, to a sporting event or to the swan boats in the Public Garden, or to the State House where he had formerly been a senator. The boys loved his sense of fun, his infectious love of learning, his sheer delight at being in their presence. (By contrast, their other grandfather, P. J. Kennedy, “wouldn’t let us cut up or even wink in his presence,” Jack remembered.) They never tired of hearing the old man’s well-worn stories, listening with rapt attention and pleading, “Tell that one again, Grandpa!”46

Rose with her five children, circa 1922. From left: Eunice, Rosemary (in foreground), Kathleen, Jack, and Joe Junior.

The fifty-nine-year-old Fitzgerald had ample time for his grandsons because his once-storied political career had sputtered. In 1916, two years after the Toodles scandal forced his withdrawal from the mayor’s race, he’d won the Democratic nomination for the U.S. Senate, but he was defeated in the general election by Republican Henry Cabot Lodge. In 1918 he rebounded to claim a seat in Congress, representing the Tenth District, only to be forced out after seven months when a congressional investigation found evidence of voter fraud. Yearning for one more shot at the limelight, Honey Fitz announced in 1922 that he would challenge Lodge a second time for the Senate, then abruptly switched his candidacy to the race for governor. One of Jack Kennedy’s earliest memories was touring the Boston wards with his grandfather, who invariably let loose his patented rendition of “Sweet Adeline” and chatted up anyone and everyone. The crowds loved him, but it was not enough: Honey Fitz lost by a wide margin. His political peak had passed.47

Jack remained frail and prone to sickness, in contrast to his robust and physically imposing older brother. But he did well enough academically at the local Edward Devotion School to enter second grade (under Miss Bicknell) at age six, a year ahead of most kids his age. And he had charm in abundance, not to mention a taste for mischief. Admonished by his mother to get serious in school, he breezily replied, “You know, I’m getting on all right, and if you study too much, you’re liable to go crazy.” That same fall, 1923, Jack and Joe Junior were caught shoplifting false mustaches from a shop, this after they formed a club in which they initiated new members by sticking pins into them. On an eatery sign reading “No dogs allowed in this Restaurant,” they scribbled “Hot” before “dogs.” On another occasion in 1923, soon after a family vacation, Jack confessed to his father, “Well, here I have been home only a few hours and the cops are chasing me already.” He had teased a little girl who had promptly gone to tell a policeman on him, whereupon Jack had raced home and hidden in the cellar until nightfall.48

It was all standard high jinks for two energetic youngsters, but for the family “executive,” Rose Kennedy, it suggested the need for a more structured environment. The point was brought home when Joe Junior cajoled Jack into racing around the block on their bikes in opposite directions and a collision occurred, sending Jack to the hospital for twenty-eight stitches. Another time she caught the two boys in the cellar, surrounded by empty milk bottles they had purloined from the neighborhood in order to resell. She opted to transfer them from Edward Devotion School to the private Noble and Greenough Lower School (soon thereafter renamed Dexter), six blocks from home, which fielded sports teams and where “there would be after-school supervised play” until 4:45 in the afternoon.49

The principal of the school, Miss Myra Fiske, had interviewed the boys in the spring of 1924 and liked what she saw. She noted Jack’s precocious intellect and wrote that she was “very glad that we decided to take this little John Kennedy. He is a fine chap.” That fall the brothers enrolled and instantly entered an elite world, a Brahmin bastion where Catholics were rare and blacks and Jews unknown. “We were probably the first and only ones who were Catholics,” Jack later reflected, which may have been an exaggeration but not by much.50

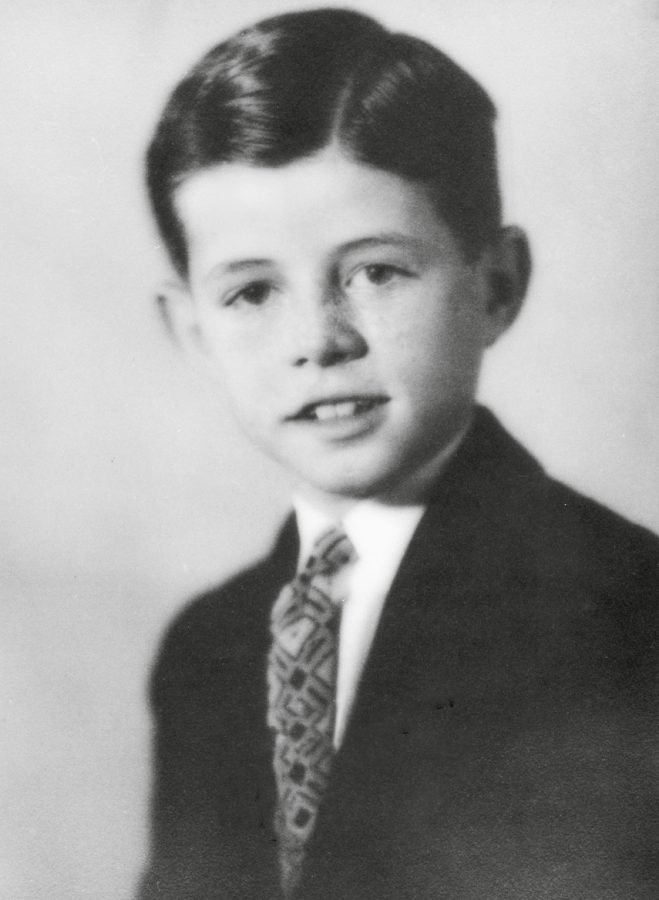

A well-groomed Jack in his Dexter School picture in 1925.

Inevitably, the taunting and bullying soon followed. “Almost everybody was a Protestant,” schoolmate Augustus Soule recalled. “I think there was a sort of snobbery, which the children adopted. I think that in those days the upper crust Boston families, of which there were a great number sending their children to the school, were very down on the Irish….To be Irish and Catholic was a real, real stigma—and when the other boys got mad at the Kennedys, they would resort to calling them Irish or Catholic.” Sometimes the fists started flying. Joe, older and bigger than his brother, not to mention more pugnacious and combative, seemed to take the encounters in stride, even challenging older boys to fight on occasion. Jack took a different tack, betting on his brother to win the scraps using a popular schoolyard currency. Soule again:

In those days, marbles: that was the big thing. You always carried a little bag of marbles in your pants pocket. And I can remember going back to my father and saying, “I need some more marbles.”

“What happened to the ones you had?” he’d ask.

“Well, I lost them all in a bet.”

“With whom?”

“I bet with Jack Kennedy.”

It’s an indelible memory I have: Joe fighting and getting all bloody, and Jack going around, betting marbles very quietly. To my mind that illustrates how completely different the two brothers were!51

For all the ostracism they suffered, however, both Joe and Jack liked the school. They played sports and eventually earned starting slots on the football team, with Joe as a bruising fullback and Jack as the lithe and scrappy quarterback.52 They had dedicated and able teachers. Miss Fiske, much beloved by the students, would gather them all together for assembly each morning, and they would recite in unison the school motto (“Our best today, better tomorrow”), followed by Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address or his second inaugural address, or a passage from literature or the Bible.53

With his lively wit and natural interest in history, Jack became Miss Fiske’s special pet. One day he asked her to take him to the historic sites of Lexington and Concord, and offered to get his father’s Rolls-Royce for the occasion. “I don’t think Rose came,” Fiske recalled many years later. “All the boys turned out to see the famous Rolls-Royce. And when it came it was a dilapidated old Ford! Jack never got over how the other boys hooted him—something had happened to the Rolls-Royce!”54