The appeal worked: “Mr. J. P. Kennedy” granted the increase.

In the seventh grade, Jack’s grades slipped into the average range. “Creditable,” his generous headmaster noted of his overall performance, while a classmate recalled that Jack’s main concern that year seemed to be “getting a date for the Saturday afternoon movie.”87 (Like many twelve-year-old boys, he was shy around girls—according to family lore, he could barely bring himself to speak to them when they started calling the house.) Perhaps, too, the disruption caused by another move affected his academic performance: in May 1929 the family moved to a twelve-room colonial on Pondfield Road in Bronxville, a one-square-mile village close to Riverdale. Central Manhattan was fifteen miles to the south. Joe paid $250,000 for the mansion (about $3.7 million today), named Crownlands, which sat on six acres of lush lawns and boasted a grass tennis court, a five-car garage, and gardener’s as well as chauffeur’s cottages. Joe Junior, Jack, and eventually Bobby rode the bus to school in Riverdale, while the girls attended the public Bronxville School.

Crownlands, however, was not Joe’s most important home purchase of the period. After their humiliating snubbing in Cohasset, the family had spent several summers fifty miles to the south, in Hyannis Port, on the Cape Cod peninsula. A small hamlet next to the larger town of Hyannis, Hyannis Port comprised about a hundred well-built, roomy, shingled or clapboard houses, separated from one another by manicured hedges or low stone walls. It was not yet the fashionable place it would become, and was far less of a summer destination for Boston’s elites than Cohasset or Bar Harbor or Newport, but it nevertheless had several things in its favor: good railway access, sandy beaches, a Catholic church, a golf club that was willing to accept Joe Kennedy as a member, and a yacht club where Joe Junior and Jack, and the other children as they grew older, could learn to sail and race. Best of all, Hyannis Port contained no concentration of “proper Bostonians” who would look down their noses at the upstart Irish Catholic Kennedys. And it gave Rose the Massachusetts anchor she desperately missed—and wanted. The family rented Malcolm Cottage, a rambling three-gabled house on Marchant Avenue, with white wooden shingles and black shutters, wide porches, two and a half acres of sloping lawn where the kids could play, a tennis court, and a private beach with a superb view of Nantucket Sound. A breakwater poked out to the left to protect against the battering of the ocean waves.

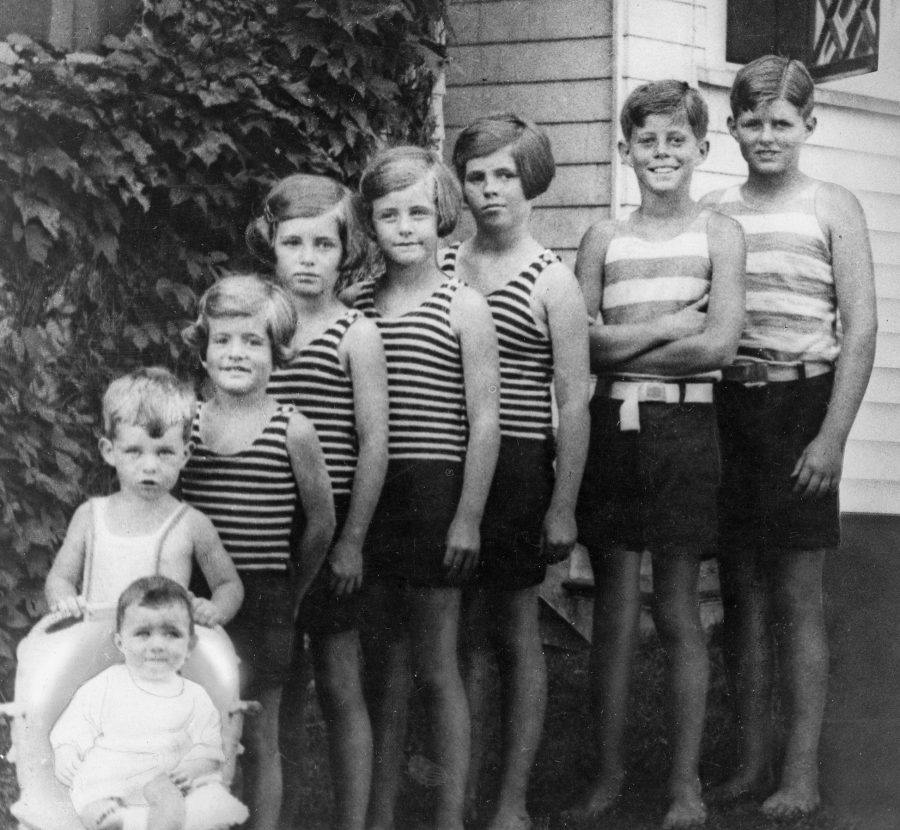

Eight little Kennedys in a row: Jean, Bobby, Pat, Eunice, Kathleen, Rosemary, Jack, and Joe Junior, in Hyannis Port, August 1928.

In 1928, Joe purchased the property in his and Rose’s names and immediately commissioned an addition that more or less doubled the home’s size and gave them fifteen rooms and nine baths, plus an RCA sound theater (unheard of in a private residence at the time) in the basement. It would become, more than any other residence, what the Kennedys meant when they spoke of “home,” the place where Joe, newly returned to the East Coast, would, during days of ceaseless activity, set about molding his children.88

For the two oldest boys in particular, Hyannis Port would take on far more meaning than the Bronxville house ever would. For their days of living at home during the academic year were rapidly coming to a close. Boarding school beckoned.