II

Did Jack resent the favoritism his parents showed toward his brother? One guesses he did, at least somewhat. According to Lem Billings, however, Jack found it fairly easy to forgive the partiality, because he never felt unfairly treated and because he treasured the space and relative anonymity his status as the second son provided. It allowed him to develop his natural inquisitiveness, to lose himself in his reading and thereby escape, if only momentarily, the fever-pitched intensity of life in the Kennedy family. Confident that he matched or outshone his older brother in mental ability, and confined to his bed by frequent maladies, Jack cultivated an intellectual prowess that no one else in the family really had, and this proved irritating to Joe Junior, who expected to be the best in everything.15

Words and their meanings interested Jack. He was the only one in the family, his sister Eunice said, “who looked things up,” the one who “did the best on all the intellectual things and sort of monopolized them.” Rose remembered that “he gobbled books,” and “not necessarily the ones I had so thoughtfully chosen for him from the PTA- and library-approved lists.” More than any of his siblings, he internalized his mother’s mantra that reading constituted “the most important instrument of knowledge.” Biography, history, tales of adventure and chivalry—these were his genres, as he devoured Robert Louis Stevenson and Sir Walter Scott and read and reread Macaulay’s Lays of Ancient Rome. The cadences of historical prose appealed to him, and he had a first-rate memory of what he read, often able to recall scenes and quotations with astonishing accuracy, even decades later. “He had a strong romantic and idealistic streak,” Rose said. “In fact, he was inclined to be somewhat of a dreamer. I often had the feeling his mind was only half occupied with the subject at hand, such as doing his arithmetic homework or picking his clothes up off the floor, and the rest of his thoughts were far away weaving daydreams….I remember him in his boyhood reading and rereading his copy of King Arthur and the Round Table.”16

One also detects from an early point a sense of ironic self-awareness and detachment concerning the Kennedy clan’s peculiarities that his older brother entirely lacked. Jack could be at once of the family and apart from it. In a family that prized punctuality, he was habitually late. Notwithstanding his mother’s obsessive focus on order and decorum, he was sloppy, forgetful, irreverent—and grew more so over time. In the winter of 1932, when two friends picked him up from the Bronxville train station, he remarked sardonically, “I want to stop by the house for a minute, and check the nursery and see if there’s anybody new in the family.” He came out and exclaimed, “By God, there is!” (It was Teddy, born on February 22.)17

As Rose later put it, from boyhood on, Jack “thought his own thoughts, did things his own way, and somehow just didn’t fit any pattern. Now and then, fairly often in fact, that distressed me, since I thought I knew what was best. But at the same time that I was taken aback, I was enchanted and amused. He was a funny little boy, and he said things in such an original, vivid way.” At least compared with his three brothers, a friend noted, Jack was “neither pushy nor calculating.” Another acquaintance expanded on the point, describing Jack as “a loner, a self-contained person. It may be that in the intensely competitive family situation he withdrew somewhat into himself, learned to keep his own counsel, and put a layer of insulation between himself and other people.”18

“Unquestionably,” historian Herbert Parmet would write, “the introspective second son was the one who resembled his father least of all.”19

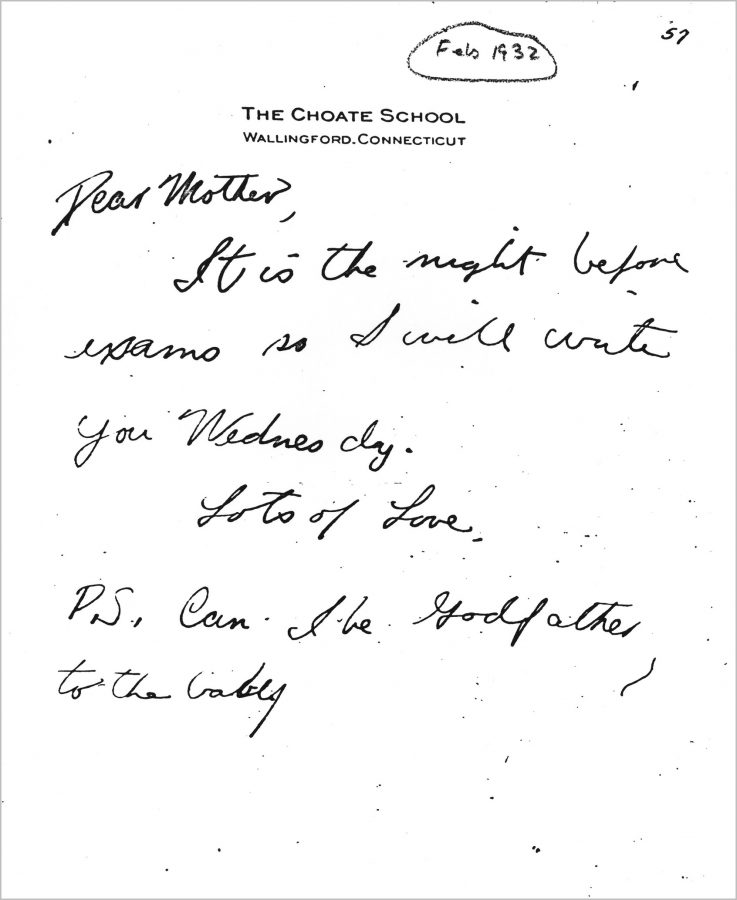

Yet Jack was also plainly devoted to his family, and fiercely loyal. He cared about what his parents thought, and during his prep school years cherished his vacation visits home. His father was now around much more, having left Hollywood behind, and his parents’ marriage seemed stronger, even with his continued serial womanizing. (Rose Kennedy in her memoirs describes the early 1930s as a golden time, as she and Joe spent long hours with each other, walking hand in hand along the shore at the Cape or through the Bronxville woodlands.) Meanwhile, Jack formed a special bond with Kick, three years younger, who possessed a quick, self-deprecating sense of humor much like his own (Joe Junior’s was more biting and sarcastic) and whose radiant charm and free-spiritedness he found enchanting. He enjoyed spending time with his other younger siblings as well—upon Teddy’s birth he asked his parents if he could be named the godfather, and was granted his wish. (He had less luck with another suggestion: that the boy be named George Washington Kennedy, since he shared a birthday with the first president.) When Teddy got a little older, it was Jack who taught him how to ride a bicycle and sail.20

What’s more, for all the differences with Young Joe and all the intense competition between them, the two brothers shared a common vitality and mutual affection. From an early age they were each other’s number-one playmate, and they had innumerable adventures together—in Brookline, in New York, in Hyannis Port, and later in prep school and college.*1 From his brother Jack learned how to sail—how to be an effective crewman, how to shift ballast in a jib, how to secure the advantage in tight races. Joe Senior recalled that his two oldest boys “were out in sailboats alone here in Hyannis Port when they were so small you couldn’t see their heads. It looked from shore as if the boats were empty.” The boys christened their first boat the Rose Elizabeth, after their mother, and spent endless hours tinkering with it and learning to sail it with consummate skill and speed. As competitive as they could be with each other, they fought much more fiercely as a team against outsiders, whether on the sporting field or in the schoolyard.21

A letter from Jack to his mother on Choate letterhead, February 1932. The P.S. reads: “Can I be Godfather to the baby.”

Years later Jack would write:

I have always felt that Joe achieved his greatest success as the oldest brother. Very early in life he acquired a sense of responsibility towards his brothers and sisters and I do not think that he ever forgot it….He would spend long hours throwing a football with Bobby, swimming with Teddy and teaching the younger girls how to sail….I think that if the Kennedy children amount to anything now or ever amount to anything, it will be due more to Joe’s behavior and his constant example than to any other factor. He made the task of bringing up a large family immeasurably easier for my father and mother for what they taught him, he passed on to us and their teachings were not diluted through him but strengthened.22

Those parental teachings centered on the importance of education, of avoiding idleness, of respecting public service, of loyalty to family. But more than anything, they were about winning. The point, Joe Senior insisted time and again, was not to play well, to compete for the sake of competing, but to defeat all comers, to secure the top prize. Even good sportsmanship paled in comparison. “We want no losers around here, only winners,” he proclaimed. From the time the children were six or seven years old, Joe and Rose entered them in swimming and sailing races, taking care to put them in different categories so they didn’t have to race each other. Always, Joe exhorted them to reach the finish line first. “The thing he always kept telling us was that coming in second was just no good,” remarked Eunice, who became an excellent sailor and all-around athlete. “The important thing was to win—don’t come in second or third, that doesn’t count, but win, win, win.” Small wonder that the Kennedys took on the reputation within the Hyannis community of being graceless competitors, of being willing to do anything to prevail. Though not an accomplished sailor himself, Joe Senior would follow his kids’ boats and make note of deficiencies he saw in performance or effort. Any slacker would be subjected to a stern talking-to at dinner in front of the family and sent in disgrace to eat alone in the kitchen.23

“My husband was quite a strict father,” Rose later acknowledged. “He liked the boys to win at sports and everything they tried. If they didn’t win, he would discuss their failure with them, but he did not have much patience with the loser.”24

One of Jack’s friends, Paul Chase, remembered seeing—and hearing—Mr. Kennedy’s win-at-all-costs approach up close. “Several times, Jack asked me to crew for him when he could not find anyone else. Once we lost badly and caught a half-hour lecture from the old man on our return to shore. He said he had watched the race and that he was disgusted with both of us. There was no sense, he claimed, in going into a race unless you did your damnedest to win, an endeavor at which we had failed miserably. He was really angry with us.”25

Chase’s anecdote hints at the possibility of a more benign assessment of Joe Kennedy’s relentlessness: that it was less about winning than about expending maximum effort in the attempt. The Kennedy kids were expected to always work harder than anyone, Robert Kennedy later wrote, even if others in the competition were more talented. “ ‘After you have done the best you can,’ he used to say, ‘the hell with it.’ ”26

The house in Hyannis Port.

Visitors to the Hyannis Port home marveled at the sheer orchestration of daytime activity. Here the summers were not holidays, filled with lassitude and soaking in the sun. Joe could not abide his offspring lounging around, even briefly, and he insisted on a packed schedule. His wife felt the same. Each evening, she posted a schedule of events for the following day—moving from tennis to golf to swimming to sailing, sometimes with professional instructors alongside. On a bulletin board next to the dining room she pinned articles from magazines and newspapers that she wanted her kids to read, and she scattered special lamps throughout the house to encourage reading.*2 Friday night was movie night in the basement, with its twenty-seven-seat theater. Saturdays were taken up with more sporting activities, and another movie or a game of charades after dinner. The younger children, supervised by a nurse, were forbidden from riding their bikes off the property; the older ones, watched over by a governess, were expected to be in the house when the lights went on at dusk. All had to be seated at the dining table five minutes before mealtimes, with dinner served promptly at 7:15 each evening. Rose had clocks placed in each room so no one would be late.27

Though the Kennedys were one of the richest families in America, guests encountered few signs of ostentatious wealth or conspicuous consumption. Quite the contrary: “We each had a napkin,” Teddy later related, “and that napkin was expected to last the entire week. If it suffered any stains—which of course is what napkins are designed to do—too bad.” The furniture in the house was comfortable but mostly ordinary; the bicycles and sporting equipment were often weathered and beaten, meant to be used until they fell apart. On birthdays the children could expect to receive no more than one or two gifts, none of them extravagant. Their weekly allowances were kept small.28

In subsequent years the suggestion would be made that the close-knit Kennedys practiced an insular solidarity and didn’t mix much with the other families of Hyannis Port, many of them Protestants from Pittsburgh. Lem Billings, for one, didn’t deny the claim, but he questioned whether anti-Catholic prejudice played much of a role. “The children were invited certainly to every party there was in Hyannis Port and there was no problem about the mixing of the Pittsburgh Protestant children and the Catholic Kennedy children,” Billings said. “I know that when I used to visit the Kennedys I knew a lot of the boys and girls in Hyannis Port better than they did, because I’d been raised with them in Pittsburgh, but this didn’t mean they weren’t invited to whatever went on. I don’t think they probably went as often as they could have, because it was a very self-sufficient family. They had everything they needed at home. They had their own movies; they had all their own athletic facilities.”29

Always, the culture of competition dominated among the children. “Which one of us is the best looking?” visitors would be asked. “Who is the funniest?” “Whose outfit do you prefer?” Seemingly friendly “touch” football games on the family lawn would turn into fierce, bruising affairs, much to the astonishment of unsuspecting guests. The gentle pleasure of skipping stones would become competitive, as would seeing whose seashell floated out the farthest into Nantucket Sound. If the family was waiting for a car and had a few minutes to kill, someone would come up with a game to play. Even board games and charades would be hotly contested. At the ages of twelve and ten, respectively, Joe Junior and Jack started winning local sailing races, and they did not let up. Eunice would soon do the same. Patricia, for her part, became an accomplished golfer. At times, Joe Senior got into the athletic act, taking on his sons in sports in which he knew he would prevail. An excellent low-handicap golfer who regularly shot in the low and mid-eighties, he would challenge Joe and Jack and beat them every time. In tennis, too, he always won comfortably, until one day when Joe Junior, then in his mid-teens, nearly bested him. That was the end of the father-son tennis matches—Kennedy preferred to hang up his racket rather than lose to one of his boys.30

Years later, one weary weekend visitor outlined the “Rules for Visiting the Kennedys”:

Anticipate that each Kennedy will ask what you think of another Kennedy’s (a) dress, (b) hairdo, (c) backhand, (d) latest public achievement. Be sure to answer “terrific.” This should get you through dinner. Now for the football field. It’s “touch,” but it’s murder. If you don’t want to play, don’t come. If you do come, play, or you’ll be fed in the kitchen and no one will speak to you. Don’t let the girls fool you. Even pregnant, they can make you look silly. Above all, don’t suggest any plays, even if you played quarterback at school. The Kennedys have the signal-calling department sewed up, and all of them have A-pluses in leadership….Run madly on every play, and make a lot of noise. Don’t appear to be having too much fun, though. They’ll accuse you of not taking the game seriously enough.31

As a philosophy of life, winning was of course problematic. On some level, Joe and Rose understood as much. Their eldest daughter, Rosemary, pretty and round-faced and sweet-natured, with a lovely smile that dimpled her cheeks, could never compete in the family’s do-or-die ethos. A mere sixteen months younger than Jack, she had been slow to crawl and then to walk. Reading and writing were difficult for her—for a long time, she scrawled her letters from the right side of the page to the left. Like Joe Junior and Jack, she had entered Edward Devotion School, but at the end of kindergarten her teachers determined that she would not be promoted to first grade but would instead repeat the year. This time she passed, with a C, but the struggles went on. She couldn’t balance herself on a bicycle or throw a ball or steer a sled like the others. At the dinner table, she struggled to manage a knife, so her meat was served precut. The intricacies of sailing eluded her; alone among her siblings, she did not have her own boat. Her parents consulted a stream of experts, including the head of the psychology department at Harvard and a specialist in Washington, D.C. “Each of them told me she was retarded,” Rose recalled, “but what to do about her, where to send her, how to help her seemed an unanswered question….I had never heard of a retarded child.”32

For a time the parents opted for what was then an enlightened approach, in the form of what today would be called “mainstreaming.” They determined Rosemary would be sent to regular school, not institutionalized in the draconian way common for the “feebleminded” (as they were then labeled) of the era. When conventional schooling proved unworkable—there were few schools in the United States then for children with special needs—they opted for homeschooling, with hired tutors and with Rose in the supervisory role. Progress was slow and fleeting. Rosemary learned to write but did not progress beyond block letters. Rose avoided using cursive in her letters to her daughter and refrained from sprinkling in French expressions when speaking to the other children, for fear of making Rosemary feel disaffected. At her insistence, Rosemary was included in most social activities, including dances at the Yacht Club, where Joe Junior and Jack, if they saw her sitting by herself, were to make sure she kept dancing, even if it cut into their own fun.33

Years afterwards, Rose would express guilt that her preoccupation with Rosemary may have made her neglectful of Jack, so close to his sister in age. “When his sister was born after him, it was such a shock, and I was frustrated and confused as to what I should do with her or where I could send her or where I could get advice about her, that I did spend a lot of time going to different places or having her tutored or having her physically examined or mentally examined, and I thought he might have felt neglected.” She expressed no similar worry about Kathleen or Eunice, born after Rosemary, who evidently could make do with less mothering than a son could.34

In September 1929, not long before her eleventh birthday, Rosemary was sent away to the Devereux School, in Berwyn, Pennsylvania, which provided specialized instruction for intellectually challenged students. She struggled to adjust to being away from home, and it did not help that the school discouraged parental visits. In mid-November, her father received his first letter and replied right away. “I cannot tell you how excited and pleased I was to get your letter,” he enthused. “You were a darling to write me so soon.” He filled her in on family goings-on and told her that Gloria Swanson would soon send her a letter and a photo, then nudged her to work hard in her studies: “I was very glad to see a lot of improvement in the report card, and I am sure that within the next couple of months it will be even better.” It didn’t happen. Though Rosemary adapted somewhat to the social environment of the school, she plateaued academically—she lacked confidence, her teachers reported, and had difficulty concentrating on any but the simplest tasks. Even elementary concepts eluded her. The parents hoped for improved performance when she returned to Devereux for a second year in 1930, and then for a third in 1931; each time they were disappointed.35