“As you know,” Joe Junior continued, “[Hitler] has passed the sterilization law which I think is a great thing. I don’t know how the Church feels about it, but it will do away with many of the disgusting specimens of men which inhabit this earth.” Overall, he summarized, the Nazi program had created “a remarkable spirit which can do tremendous good or harm, whose fate rests with one man alone.”*2, 86

Having had their fill of Munich, Jack and Lem drove on to Nuremberg. The quality of the German roads awed them—especially the new autobahns, the world’s first interstate highways—and Jack insisted on picking up hitchhikers and quizzing them on the state of affairs and their views of the Nazi regime. In Nuremberg they learned that Hitler would be holding a rally in the city three days hence; they contemplated staying around for it (and later regretted not doing so) but once again found the haughtiness of the people hard to take. They hit the road again—“Started out as usual except this time we had the added attraction of being spitten on,” as Jack laconically put it in his diary, without further details—and made their way for England via Holland, Belgium, and finally the port of Calais.87

Time was now of the essence, as Jack wanted desperately to get to London to see Joe Junior and Kick before they returned to America. He made it in time, shopping with Kick rather than joining his brother on a visit with Harold Laski. He also met with his mother in Southampton, dutifully complimenting her on her latest Parisian fashion purchases and helping himself to what Lem in his diary referred to as a “mix of tomato juice & plenty of chocolate.”88 Back in London, he developed a bad case of hives, perhaps from the chocolates, prompting a frantic search by Billings for a doctor who would pinpoint the problem. One physician after another was stumped, until suddenly one morning the hives disappeared as fast as they had arrived. Soon after, the two young men embarked on the journey home to the United States, with a stop in Scotland on the way.

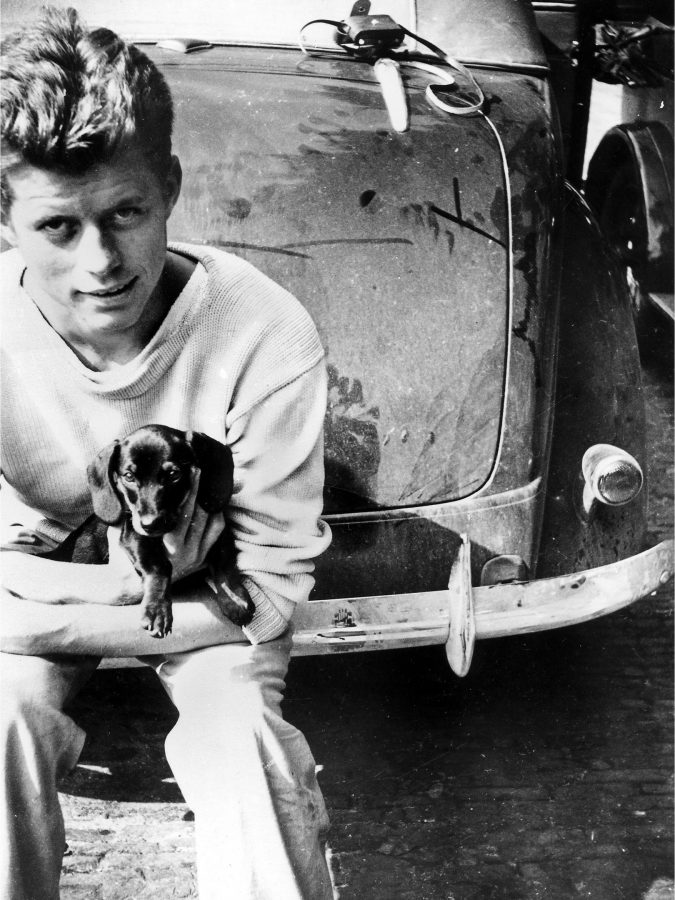

Jack with Dunker, the dachshund he and Lem bought for $8 at a stop on the road to Nuremberg, and which Jack intended as a gift for Olive Cawley. Soon after this photo was taken, Jack started wheezing and sneezing; a German doctor determined he was allergic to dogs. In Utrecht, someone agreed to buy Dunker for $3.

It’s tempting in hindsight to attach weighty importance to lengthy jaunts like the one Jack Kennedy and Lem Billings had in the summer of 1937. To do so isn’t always wise. The two were in most respects the same young men after the two-and-a-half-month trip that they had been before. Still, the adventure left an impression. In Jack’s case, his international sensibility, encouraged by his mother from the time he was a young boy, deepened, and one is struck as well by the increasingly sophisticated nature of his queries as the journey progressed, until by the end they were as serious-minded, if not yet as well developed, as those of professional journalists and diplomats. His determination to form independent judgments rather than simply echo his father’s assessments or give in to lazy isolationist clichés about “foreigners” grew stronger. Most portentously, one sees in the young Kennedy that summer an emerging capacity and willingness to view world affairs in contextual, dispassionate terms—a contrast with his father, who tended always to view the outside world mostly in terms of what it meant for himself and his family.89

As it happened, this tendency on the part of Joseph P. Kennedy to personalize all public policy issues would soon land him in a heap of trouble, and in time cause a further separation in the worldviews of father and son.