IV

P. J. Kennedy’s success was one sign among many that the Irish had arrived in Massachusetts politics. The sheer numbers tell the tale, just as farsighted Yankee Protestants had long feared. By the mid-1870s, with the second generation now in adulthood, with the birth rate high and the mortality rate waning, and with more transplants arriving from the motherland by the week (emigration slowed after the end of the famine, but it never disappeared), Irish Americans represented more than a third of Boston’s population of 300,000 and were fast approaching 50 percent.31 The Beacon Hill bluebloods might retain control of the financial and cultural institutions and the social pecking order, but the political contest was a different story. The Boston Irish were electing state legislators and city aldermen, and in 1882 one of their own, Patrick Collins, was elected to the U.S. Congress. Two years after that, Hugh O’Brien became the city’s first Irish and first Catholic mayor. Meanwhile, ward bosses such as Kennedy and the legendary Martin “the Mahatma” Lomasney wielded great power in their areas, as did the cocky John F. Fitzgerald, the rakish ruler of the North End, who in time would become P. J.’s in-law.32

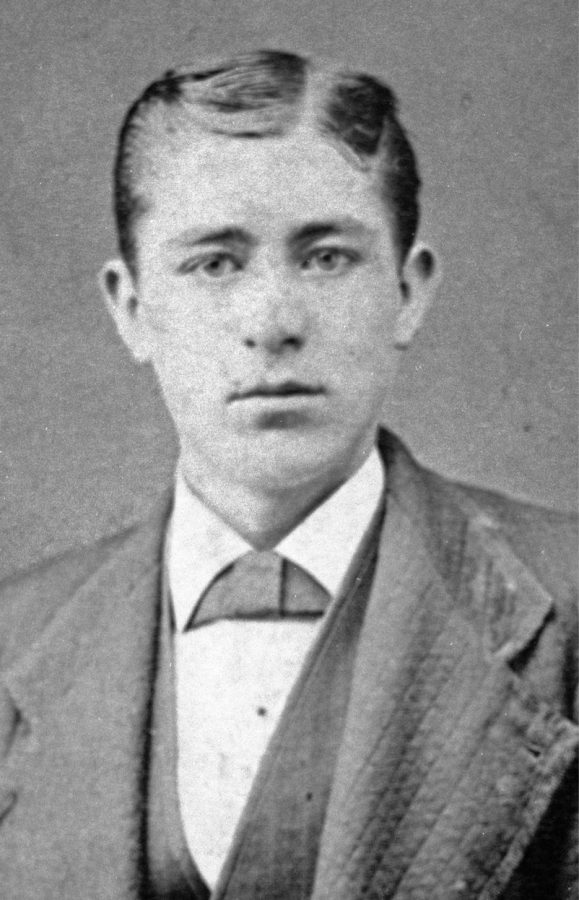

Patrick Joseph “P. J.” Kennedy, circa 1878, in his youthful, pre-mustachioed days.

Mary Augusta “Mame” Kennedy, date unknown.

As Kennedy prospered in business and politics, he also found success in his personal life. He began courting Mary Augusta Hickey, a tall, handsome woman with stately grace and formidable intelligence who was two years his senior and hailed from an affluent Irish family in Brockton, then an upscale suburb. Her Irish-born father, James, was a prosperous businessman, and her three brothers had all done well: Charles was the mayor of Brockton, Jim was a police captain, and John, a graduate of Harvard Medical School, was a doctor in nearby Winthrop. If any family can be said to have represented the so-called lace-curtain Irish (solidly middle class, and to be distinguished from the down-at-the-heels “shanty” Irish), it was the Hickeys. On Thanksgiving eve 1887, P. J. and Mary Augusta (“Mame,” he called her) were married at Sacred Heart Church. A little over nine months later, on September 6, 1888, they had their first child, Joseph Patrick Kennedy. In 1891 followed Francis Benedict, who died of diphtheria about a year later, then Mary Loretta, in 1892, and Margaret Louise, in 1898.

Bridget Kennedy, for her part, lived long enough to see her son find success in the world in which she had struggled to survive, and to see his first son born into it. She died in her home in December 1888, at age sixty-seven.33

Her daughter-in-law, it turned out, was much like her in one respect: she was intensely ambitious for her son. Just as P. J. had been the star in his family firmament, so Joseph would be in his, the child on whom Mary Augusta lavished her primary attention. “My Joe,” she called him as she immersed herself in his daily life, doting on him, engaging him on his school activities, and reminding him that his uncle John had gone to Harvard. Joe felt the bond, rushing home from the local parish school every day to have lunch with her. “He missed me,” Mary Augusta remembered delightedly years later, after he had begun to make his mark on Boston society. “He missed me and wanted to hurry home and see me again.”34

Initially, the family resided at 151 Meridian Street, in the business district of East Boston, a three-story dark-red brick house, which we would today call a townhouse and which was near one of P. J.’s taverns. But before long they moved up—in both senses of the word—to a large house at 165 Webster Street, an elegant, tree-lined avenue on Jeffries Point, overlooking the harbor, with a backyard that sloped down to the water. Young Joe had the run of the place, the Irish servant girls treating him like a young prince and his sisters constantly deferring to him. “I thought he was a god,” Margaret said of her brother many years afterwards. “I’d be thrilled even if he asked me to put something away for him—anything, just as long as he noticed me.” Loretta, meanwhile, remarked on the authority Joe seemed to possess within the family, even at a young age. In this largely female world, he was the pivot around which all things circled, an arrangement he took to be the normal order of things.35

The details of Joe Kennedy’s boyhood are largely lost to us, in part because in later years he showed little interest in talking about it. He offered few clues as to the nature of life within the household, or about his relationships with his sisters, though in adulthood he corresponded with them via letters and phone calls and backed them financially.36 Never one to look back, Joe was also keen to hide the fact that he had grown up in a life of privilege, wanting for nothing and with advantages others did not have. (“Joe did not come in on a raft,” his niece Mary Lou McCarthy would subsequently remark. “His life was very comfortable.”37) To admit such a thing would be to admit that he might not be fully responsible for his own success, and this was something Kennedy was loath to do. A devotee in his boyhood of Horatio Alger Jr. books, he loved their up-from-nothing, against-all-odds theme and came firmly to believe that anyone with God-given talents who worked hard could achieve great things. Kennedy never said or implied he was a child of poverty or that he faced undue hardships growing up, but he did push the narrative that his success was entirely his own.38

Young Joe looked up to his father, and recalled with satisfaction being allowed to tag along with him to campaign rallies and torchlight parades. He took pride in being the son of one of East Boston’s most prominent figures, someone who had achieved rare distinction in business and politics. He admired his father’s shrewdness and talent for organization, could see the respect he carried in the community. Yet there was also a sense, no doubt encouraged by his strong-willed mother, Mary Augusta, that he should set his own sights higher, that his father’s success, however great, was too bounded, too local. And indeed, P. J. Kennedy, for all his determination to make good, did not have a driving ambition to extend his influence beyond his corner of the city. A mediocre public speaker with scant interest in chatting up voters on street corners, Kennedy preferred to wield his political power from behind the scenes. His tenure in the state house was undistinguished, and he achieved little after being elected to the state senate in 1892. After two one-year terms in the upper chamber, he stepped aside. East Boston was the heart of his political world; being ward boss was his calling.39

Mary Augusta felt differently. Although she was proud of her husband’s accomplishments and of her Irish roots, she also chafed at them, aware that among the “proper” Bostonians against whom she measured herself and her family—the Yankee Protestants of Beacon Hill and the Back Bay—parochial politics of the type her husband practiced was not altogether honorable. And she was less willing than P. J. to accept the unwritten regulations of the social game: equal but separate. She wanted something more for her Joe, wanted him to be on equal footing with the Brahmins who ruled Boston society, wanted him to go to Harvard, not the Jesuit-run Boston College or Holy Cross, where the lace-curtain Irish typically sent their sons. She urged him to introduce himself as “Joe” rather than “Joe Kennedy,” the better to hide his Irish heritage.40 One detects her strong influence behind the couple’s decision to send the boy, upon his completion of the seventh grade in parochial school in 1901, to Boston Latin, the oldest and most distinguished public school in the country, whose alumni included five signers of the Declaration of Independence (Franklin, Hancock, Hooper, Paine, and Samuel Adams) as well as Cotton Mather, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry Ward Beecher. By the start of the twentieth century, most upper-class Protestants no longer sent their sons to Boston Latin—they preferred the even more exclusive Northeast prep schools now dotting the landscape—but it was still a forbidding Yankee institution, and even the preternaturally confident Joe must have felt some butterflies on his first day, September 12, as he boarded the ferry that would carry him across the canal and into an environment wholly new to him.41

The curriculum was classical and rigorous, focused on preparing students for the Harvard entrance examinations. Six years of Latin were compulsory, as were six years of science, math, and English, five years of history, and four years of French. In this hothouse atmosphere, Joe struggled. Though he did not lack for brains—he possessed a fine analytical intelligence and a superior memory—his transcript shows a string of C’s and D’s and failing grades in elementary French, elementary physics, and advanced Latin. So poorly did he perform in the classroom that he had to repeat his senior year. Curiously, these dismal results did not seem to dampen the boy’s ego, at least in any lasting way. He looked with scorn on the bookish and humorless types who grubbed for grades and focused his energies instead on the social realm and on athletic pursuits.42