The two people Bruno missed most of all from home were Grandfather and Grandmother. They lived together in a small flat near the fruit and vegetable stalls, and around the time that Bruno moved to Out-With, Grandfather was almost seventy-three years old which, as far as Bruno was concerned, made him just about the oldest man in the world. One afternoon Bruno had calculated that if he lived his entire life over and over again eight times, he would still be a year younger than Grandfather.

Grandfather had spent his entire life running a restaurant in the centre of town, and one of his employees was the father of Bruno’s friend Martin who worked there as a chef. Although Grandfather no longer cooked or waited on tables in the restaurant himself, he spent most of his days there, sitting at the bar in the afternoon talking to the customers, eating his meals there in the evening and staying until closing time, laughing with his friends.

Grandmother never seemed old in comparison to the other boys’ grandmothers. In fact when Bruno learned just how old she was – sixty-two – he was amazed. She had met Grandfather as a young woman after one of her concerts and somehow he had persuaded her to marry him, despite all his flaws. She had long red hair, surprisingly similar to her daughter-in-law’s, and green eyes, and she claimed that was because somewhere in her family there was Irish blood. Bruno always knew when a family party was getting into full swing because Grandmother would hover by the piano until someone sat down at it and asked her to sing.

‘What’s that?’ she always cried, holding a hand to her chest as if the very idea took her breath away. ‘Is it a song you’re wanting? Why, I couldn’t possibly. I’m afraid, young man, my singing days are far behind me.’

‘Sing! Sing!’ everyone at the party would cry, and after a suitable pause – sometimes as long as ten or twelve seconds – she would finally give in and turn to the young man at the piano and say in a quick and humorous voice:

‘La Vie en Rose, E-flat minor. And try to keep up with the changes.’

Parties at Bruno’s house were always dominated by Grandmother’s singing, which for some reason always seemed to coincide with the moment when Mother moved from the main party area to the kitchen, followed by some of her own friends. Father always stayed to listen and Bruno did too because there was nothing he liked more than hearing Grandmother break into her full voice and soak up the applause of the guests at the end. Plus, La Vie en Rose gave him chills and made the tiny hairs on the back of his neck stand on end.

Grandmother liked to think that Bruno or Gretel would follow her onto the stage, and every Christmas and at every birthday party she would devise a small play for the three of them to perform for Mother, Father and Grandfather. She wrote the plays herself and, to Bruno’s way of thinking, always gave herself the best lines, though he didn’t mind that too much. There was usually a song in there somewhere too – Is it a song you’re wanting? she’d ask first – and an opportunity for Bruno to do a magic trick and for Gretel to dance. The play always ended with Bruno reciting a long poem by one of the Great Poets, words which he found very hard to understand but which somehow started to sound more and more beautiful the more he read them.

But that wasn’t the best part of these little productions. The best part was the fact that Grandmother made costumes for Bruno and Gretel. No matter what the role, no matter how few lines he might have in comparison to his sister or grandmother, Bruno always got to dress up as a prince, or an Arab sheik, or even on one occasion a Roman gladiator. There were crowns, and when there weren’t crowns there were spears. And when there weren’t spears there were whips or turbans. No one ever knew what Grandmother would come up with next, but a week before Christmas Bruno and Gretel would be summoned to her home on a daily basis for rehearsals.

Of course the last play they performed had ended in disaster and Bruno still remembered it with sadness, although he wasn’t quite sure what had happened to cause the argument.

A week or so before, there had been great excitement in the house and it had something to do with the fact that Father was now to be addressed as ‘Commandant’ by Maria, Cook and Lars the butler, as well as by all the soldiers who came in and out of there and used the place – as far as Bruno could see – as if it were their own and not his. There had been nothing but excitement for weeks. First the Fury and the beautiful blonde woman had come to dinner, which had brought the whole house to a standstill, and then it was this new business of calling Father ‘Commandant’. Mother had told Bruno to congratulate Father and he had done so, although if he was honest with himself (which he always tried to be) he wasn’t entirely sure what he was congratulating him for.

On Christmas Day Father wore his brand-new uniform, the starched and pressed one that he wore every day now, and the whole family applauded when he first appeared in it. It really was something special. Compared to the other soldiers who came in and out of the house, he stood out, and they seemed to respect him all the more now that he had it. Mother went up to him and kissed him on the cheek and ran a hand across the front of it, commenting on how fine she thought the fabric was. Bruno was particularly impressed by all the decorations on the uniform and he had been allowed to wear the cap for a short period, provided his hands were clean when he put it on.

Grandfather was very proud of his son when he saw him in his new uniform but Grandmother was the only one who seemed unimpressed. After dinner had been served, and after she and Gretel and Bruno had performed their latest production, she sat down sadly in one of the armchairs and looked at Father, shaking her head as if he were a huge disappointment to her.

‘I wonder – is this where I went wrong with you, Ralf?’ she said. ‘I wonder if all the performances I made you give as a boy led you to this. Dressing up like a puppet on a string.’

‘Now, Mother,’ said Father in a tolerant voice. ‘You know this isn’t the time.’

‘Standing there in your uniform,’ she continued, ‘as if it makes you something special. Not even caring what it means really. What it stands for.’

‘Nathalie, we discussed this in advance,’ said Grandfather, although everyone knew that when Grandmother had something to say she always found a way to say it, no matter how unpopular it might prove to be.

‘You discussed it, Matthias,’ said Grandmother. ‘I was merely the blank wall to whom you addressed your words. As usual.’

‘This is a party, Mother,’ said Father with a sigh. ‘And it’s Christmas. Let’s not spoil things.’

‘I remember when the Great War began,’ said Grandfather proudly, staring into the fire and shaking his head. ‘I remember you coming home to tell us how you had joined up and I was sure that you would come to harm.’

‘He did come to harm, Matthias,’ insisted Grandmother. ‘Take a look at him for your evidence.’

‘And now look at you,’ continued Grandfather, ignoring her. ‘It makes me so proud to see you elevated to such a responsible position. Helping your country reclaim her pride after all the great wrongs that were done to her. The punishments above and beyond—’

‘Oh, will you listen to yourself!’ cried Grandmother. ‘Which one of you is the most foolish, I wonder?’

‘But, Nathalie,’ said Mother, trying to calm the situation down a little, ‘don’t you think Ralf looks very handsome in his new uniform?’

‘Handsome?’ asked Grandmother, leaning forward and staring at her daughter-in-law as if she had lost her reason. ‘Handsome, did you say? You foolish girl! Is that what you consider to be of importance in the world? Looking handsome?’

‘Do I look handsome in my ringmaster’s costume?’ asked Bruno, for that was what he had been wearing for the party that night – the red and black outfit of a circus ringmaster – and he had been very proud of himself in it. The moment he spoke he regretted it, however, for all the adults looked in his and Gretel’s direction, as if they had forgotten that they were there at all.

‘Children, upstairs,’ said Mother quickly. ‘Go to your rooms.’

‘But we don’t want to,’ protested Gretel. ‘Can’t we play down here?’

‘No, children,’ she insisted. ‘Go upstairs and close the door behind you.’

‘That’s all you soldiers are interested in anyway,’ Grandmother said, ignoring the children altogether. ‘Looking handsome in your fine uniforms. Dressing up and doing the terrible, terrible things you do. It makes me ashamed. But I blame myself, Ralf, not you.’

‘Children, upstairs now!’ said Mother, clapping her hands together, and this time they had no choice but to stand up and obey her.

But rather than going straight to their rooms, they closed the door and sat at the top of the stairs, trying to hear what was being said by the grown-ups down below. However, Mother and Father’s voices were muffled and hard to make out, Grandfather’s was not to be heard at all, while Grandmother’s was surprisingly slurred. Finally, after a few minutes, the door slammed open and Gretel and Bruno darted back up the stairs while Grandmother retrieved her coat from the rack in the hallway.

‘Ashamed!’ she called out before she left. ‘That a son of mine should be—’

‘A patriot,’ cried Father, who perhaps had never learned the rule about not interrupting your mother.

‘A patriot indeed!’ she cried out. ‘The people you have to dinner in this house. Why, it makes me sick. And to see you in that uniform makes me want to tear the eyes from my head!’ she added before storming out of the house and slamming the door behind her.

Bruno hadn’t seen much of Grandmother after that and hadn’t even had a chance to say goodbye to her before they moved to Out-With, but he missed her very much and decided to write her a letter.

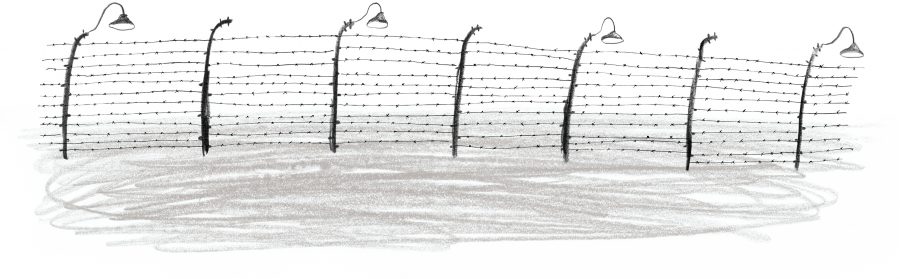

That day he sat down with a pen and paper and told her how unhappy he was there and how much he wished he was back home in Berlin. He told her about the house and the garden and the bench with the plaque on it and the tall fence and the wooden telegraph poles and the barbed-wire bales and the hard ground beyond them and the huts and the small buildings and the smoke stacks and the soldiers, but mostly he told her about the people living there and their striped pajamas and cloth caps, and then he told her how much he missed her and he signed off his letter ‘your loving grandson, Bruno’.