Jack’s health, meanwhile, continued to be better than it had been during his prep school years and his Princeton interlude but less good than it should have been. He went on suffering bouts of vague maladies. There were periodic trips to the infirmary and more than occasional missed classes. During fall football season, in which he suited up for the junior varsity team but saw little playing time, he suffered a debilitating back injury, though it did not prevent him from swimming that winter for Harvard against Penn, Columbia, Princeton, and Dartmouth.35 In February 1938, he paid a brief return visit to the Mayo Clinic, in Minnesota, to undergo tests relating to ongoing stomach and colon problems, and at the end of the month he found himself in the Harvard infirmary with a bad case of the flu. An intestinal infection followed in March that compelled a stay of several days in New England Baptist Hospital. His weight dropped through the spring, in spite of the ice cream machine his friends installed for him at the Spee Club.36

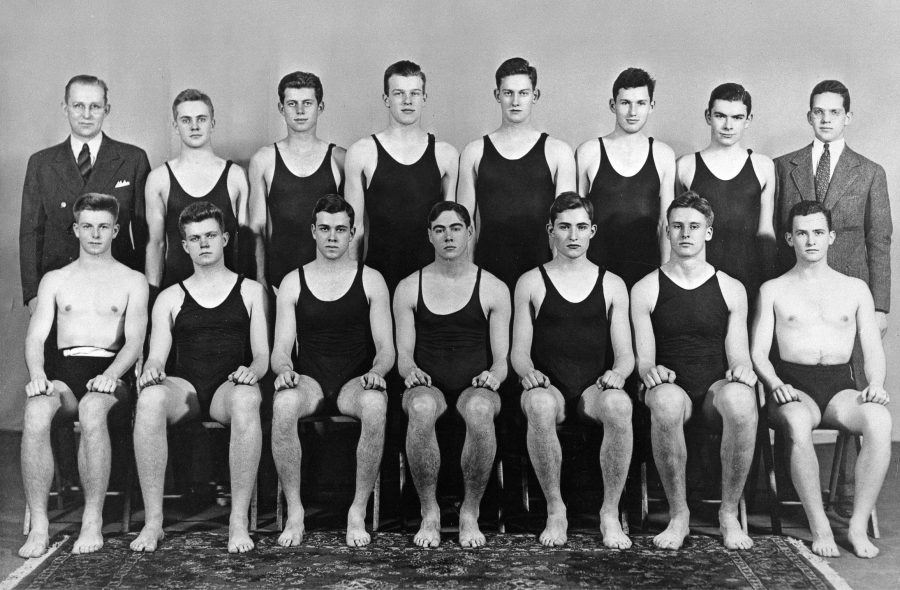

The Harvard swim team in 1938. Kennedy is standing, third from left.

All the while, the astonishing Kennedy energy and vitality kept him going. Torby Macdonald marveled at the ceaseless activity, not least when it came to women. They gravitated toward Jack more than ever, drawn in by his winning smile and wry sense of humor, and by a lighthearted, peppery flirtatiousness that never seemed to cross the line into vulgarity or predatory encroachment. His relationship with Olive Cawley having sputtered to an end with his failed pursuit of her virginity, he now made up for lost time.37 Housemates would watch in wonderment as one or another Boston waitress came calling at Winthrop House. Or they’d see him zoom by on Memorial Drive or Garden Street in his Ford convertible, accompanied by a young woman from Radcliffe or Wellesley or Mount Holyoke or another of the women’s colleges in the area—seemingly a different girl each time.

His success with the opposite sex bemused him, at least in the early going. After all, he said to Billings, he wasn’t much better looking than other guys. The explanation, he went on, had to be in his personality. Billings, when asked by an interviewer long afterwards, saw a combination of factors: “Whenever he was home, there was always a girl around—usually it was a different girl each time. Almost, without exception, every girl he showed any interest in became very fond of him. I think the reason for this was that he was not only attractive but also he had tremendous interest in girls. They really liked him and he was very, very successful. This was important to him because he wanted to be successful in this area. He really enjoyed girls.”38 Like father, like son, in other words—and like older brother.

When Boston seemed too confining, Kennedy and Macdonald would drive to Smith or Vassar for double dates, taking turns behind the wheel. (Whenever Torby drove, Jack would snooze, astonishing his friend with his ability to fall asleep almost at will.) Or Jack would take a weekend jaunt to New York City, where he’d meet up with Lem Billings and Rip Horton and head to the fashionable Stork Club, on East Fifty-third Street. “In those days, that was the place to go,” Billings later said, “and the Stork Club was very anxious to attract young people. They particularly encouraged young models and pretty girls to come there, and they made things easier for the boys who brought pretty girls….There were presents for the girls and champagne. Of course we were very careful never to have more than one drink each while we were there—we couldn’t spend any more than that. Jack didn’t mind spending on the same basis as I did. Jack wasn’t much of a drinker, so it wasn’t any hardship to take one drink. He liked to dance very much.”39

“Jack certainly never made anyone conscious of his wealth,” Macdonald related. “In fact there were times when he had a disconcerting lack of consciousness about it himself. Once we double-dated a couple of girls and dined in a rather expensive Boston restaurant. When the bill came it amounted to something like $12. Jack dug into his pockets and came up with exactly nothing. I checked my wallet and found eight one-dollar bills. We had to borrow from the girls to get out of the place.”40

If not in his spending habits, Jack Kennedy’s sense of entitlement manifested itself in other ways. He was a notoriously reckless driver, with a fondness for putting the pedal to the floor and maneuvering quickly even in tight spaces. On one occasion in Allston, across the river from Cambridge, near the gray-arcaded horseshoe of Harvard Stadium, he got into a row with a woman after he backed into her car. Subsequently, he told Lem, the woman reported him to the police, “saying I had leered at her after bumping her four or five times, which story has some truth although I didn’t know I was leering.” Instead of taking the heat, Jack pretended he had loaned the car to Billings and urged him to agree. “Tell [the officer] you come from Florida if he asks for your license—also you’re sorry and you realize you should not have done it, etc….You write him a gracious letter and admit it,” he instructed. Lem, dutiful as always, went along.41