Having thus admonished his father, Jack added a plea: “Of course, I do not mean you should advocate war, but you might explain with some vigour your ideas on how vital it is for us to supply England. You might work in how hard it is for a democracy to get things done unless it is scared and how difficult it is to get scared when there is no immediate menace—We should see that our immediate menace is not invasion, but that England may fall—through lack of our support.” History would not look kindly upon an America that followed Chamberlain’s lead, and in the future, “as we look back, we may be shocked at our present lack of vigour.” Jack loyally acknowledged that the picture of his father in the popular imagination was wrong—the older man did not oppose all assistance to Britain. But he warned that perception was reality: in the common view “you are [an] appeaser + against aid—This you have to nip.”52

Soon thereafter, following some hobnobbing in Hollywood (at one party he chatted up Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy, and he roomed for a few days with aspiring actor Robert Stack) and an academic conference in Riverside at which he served as rapporteur, Jack Kennedy left California behind.*2 He missed his East Coast social life, missed his family. For a time he exchanged love letters with Harriet Price; as the weeks passed the letters grew more infrequent, then they ceased altogether. In one of her last notes, Harriet referred to Jack’s fatalistic view of life when she informed him that she’d almost been killed in a car accident—she was thrown out of the car yet somehow emerged unscathed. “But as you say, ‘That’s the way it goes.’ ”53

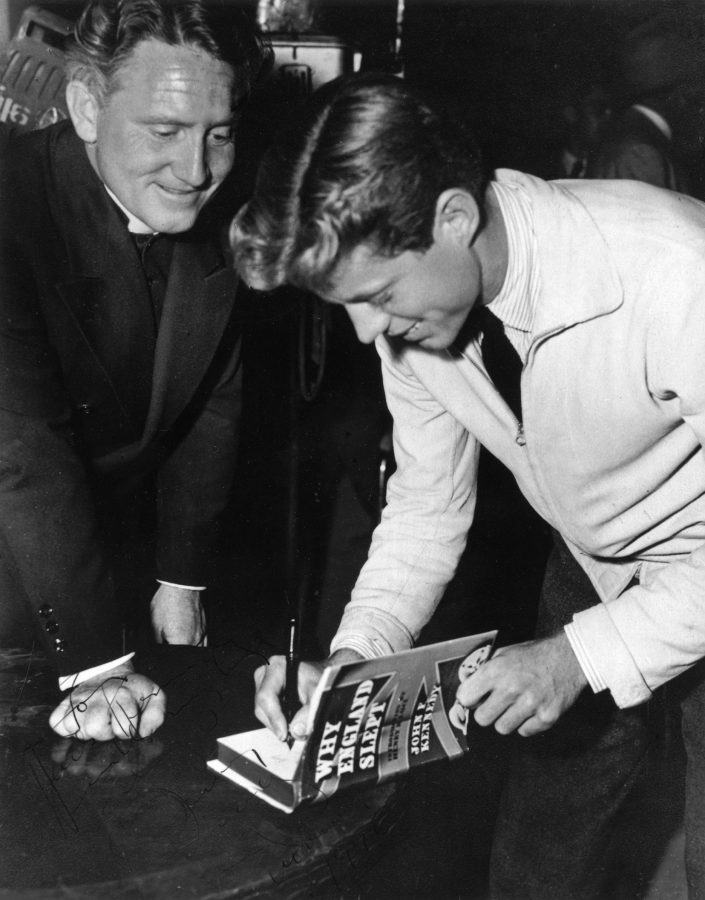

A young author in Hollywood signs his book for actor Spencer Tracy.

V

Dr. Sara Jordan of the Lahey Clinic, in Boston, took one look at Jack Kennedy and was aghast. It was the morning of December 9, 1940, and he had arrived in her office for an examination. The sojourn in the California sunshine, she could see, far from restoring the young man to robust good health, seemed to have had the opposite effect, as he now weighed less than before he went. He looked emaciated and drawn. Jordan insisted that Jack return to Boston after Christmas for further tests at New England Baptist Hospital and urged him to avoid any further full-time studies until fall 1941. He did as instructed, spending part of January 1941 in confinement in the hospital. From his bed there he penned a short article—his first publication since his book appeared—for the New York Journal-American, under the headline “Irish Bases Are Vital to Britain.”

Much to Jack’s satisfaction, his father had taken the advice in his December letters to heart, at least partially. When, in December, the Roosevelt administration called on Congress to pass a “Lend-Lease” bill—the United States would lend or lease military goods to the British, much as one lends a garden hose to a neighbor to fight a fire, out of compassion as well as enlightened self-interest—Joe Kennedy expressed opposition. It would be a giant step toward war, he declared. Some in the administration worried that Kennedy might go further, deploying his bottomless resources to try to thwart the plan. As the days passed, however, he shifted ground until, in a highly anticipated address on NBC Radio on January 18, he dropped his opposition. On the twenty-first, one day after Franklin Roosevelt’s third inauguration, Kennedy crushed the hopes of Capitol Hill isolationists by offering not a peep of dissent to Lend-Lease when he appeared before a congressional committee considering the bill.54

Admittedly, more than Jack’s advocacy was at work. For one thing, the elder Kennedy hoped against hope to be appointed to another high-level post in the administration, and thought it prudent to go along with the president’s wishes. For another, now that he was back on American soil, he better understood that his isolationist cause was faltering. The weight of public opinion strongly backed Lend-Lease, backed aid for Britain. Against his predictions, the British were holding on, but they were desperate for more help, and Kennedy could see that most Americans wanted to give it. They were buying the administration’s arguments, he perceived, and he saw as well the growing influence of radio correspondents such as Edward R. Murrow, whose rich, low-key, nicotine-scorched reports from wartime London kept Americans spellbound. (“This…is London,” he would begin each broadcast, a distinctive hesitation suggested by his old high school teacher.) Murrow was resolutely pro-British, and there is no doubt his broadcasts bolstered the interventionist side in the U.S. debate by stressing Winston Churchill’s greatness and England’s bravery. More than that, though, correspondents like Murrow, speaking through the blaring of sirens, the whine of aircraft, and the roar of bomb bursts, brought the war home to Americans in a uniquely powerful way, one that made them feel closely connected to sufferers an ocean away. As the writer Archibald MacLeish said of Murrow’s reports, “Without rhetoric, without dramatics, without more emotion than needed be, you destroyed the superstition of distance and of time.”55

Joe Junior, meanwhile, argued the isolationist position more strongly than ever. Intensely stubborn by nature, he could also be tone-deaf in framing his arguments, and combative to the point of recklessness. Through the winter of 1941 he railed against the Lend-Lease measure, and he didn’t let up even after Congress approved the bill by comfortable margins, in early March, thereby granting the executive branch extraordinary new powers. (The president alone would decide what to lend and to whom.) In a Ford Hall Forum in Boston on January 6, Joe insisted that the United States could not afford to bolster a doomed Britain and should instead prepare to implement a bartering system with Germany. Better to accede to Nazi domination of Europe, he went on, than to leap into a war that would strain the American economy beyond the breaking point and let loose the forces of radicalism. Late that month, Joe told another Boston audience that America should even resist sending food convoys if doing so risked pulling the nation into the war. He stuck to that position in the weeks thereafter.56

Jack thought his pugnacious brother foolhardy to speak so dogmatically on the issue, not to mention wrong on the merits. But Joe was also his sibling, so there could be no question of denouncing him. Jack contented himself during these weeks with quietly endorsing the administration’s policy and thinking about what he should do next. Planning too far ahead was pointless, he believed, as war clouds threatened both in the west and in the east. In March, he again asked Harvard to send his transcript to Yale Law School, but he seemed no more committed to the prospect of legal studies than he had been the year before, and apparently did not submit a new application. His health stabilized, he indulged his interest in travel, visiting first Bermuda and then South America, where his mother and Eunice were already touring. Jack flew from Miami to join them in Rio de Janeiro, then moved on without them to Argentina. The pro-Nazi mood in Buenos Aires stunned him, as did the palpable undercurrent of anti-Americanism. From there it was on to Uruguay and Chile by plane, then, on June 10, by cruise ship from Valparaíso back to the States, with stops in Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia, followed by passage through the Panama Canal.57

Throughout the trip there had been ominous signs that world tensions were ratcheting up still further. In the Far East, the Japanese were pushing deeper into China and strengthening their hold on Southeast Asia. In the Atlantic, meanwhile, British shipping losses to the German U-boats rose to perilous heights that spring, prompting pleas from Churchill and top White House aides for U.S. convoys. In a major speech on May 27, FDR did not call for convoys—he feared moving too far ahead of public opinion—but he left little doubt that he thought developments in the Atlantic could bring the United States into the war at almost any moment. Announcing an unlimited state of emergency, the president warned of Hitler’s global ambitions and pointed to the threats to island outposts such as Iceland, Greenland, and the Azores, from which the Nazis could launch aerial attacks on North and South America. Behind the scenes, U.S. negotiators worked to bring Iceland under American protection, and in June Roosevelt extended the U.S. defense perimeter well out into the North Atlantic.58

Then, on June 22, Hitler launched his boldest move of the war. Tossing out his August 1939 pact with Stalin, he ordered a massive assault on the Soviet Union, involving 3.2 million men, 3,600 tanks, and 600,000 motorized vehicles along a front that stretched for two thousand miles. Supporting aircraft numbered 2,500, and there was a throwback to the battles of old: 625,000 horses used for transport.59 It was the largest land operation in history. For the Western Allies the invasion, code-named Operation Barbarossa, had one salutary effect in the short term: it eased the pressure on Great Britain. It also served to draw London and Washington officials closer together and to bring the United States nearer to active participation in the Battle of the Atlantic. Roosevelt, convinced that Soviet survival was crucial to Nazi Germany’s defeat, pledged to provide Lend-Lease assistance to Stalin’s government, despite deep aversion among many in Washington to helping the Kremlin leader—who had systematically and ruthlessly purged dissidents, signed a pact with Hitler, and brutalized eastern Poland.

It was a stunning development, changing the whole complexion of the war. Earth-shattering events had passed in a blur. Jack, still on his cruise ship en route home, was pondering the implications when there arrived news of a more personal nature: his brother had volunteered for military service! It seemed unthinkable: through April and into May, Joe Junior had continued his strident anti-war and anti-administration rhetoric, insisting in an address at Temple Ohabei Shalom, in Brookline, on April 29 that it would be “perfectly feasible for the United States to exist as a nation, regardless of who wins the war.”60 American escorts for ships carrying Lend-Lease aid would be a terrible mistake, he had added, as it would inevitably lead to the sending of men. Yet mere weeks later, this co-founder of the Harvard Committee Against Military Intervention, this frequent admirer of Hitler’s Germany, this fervent proponent of America First principles, opted to forgo the final year of law school and sign up for the Naval Aviation Cadet Program of the U.S. Navy Reserve.

Joe Senior was dumbfounded. His firstborn not only had volunteered but had chosen the most dangerous branch of service, naval aviation. The Ambassador (as he was now often called, even as a private citizen) offered to pull strings and get Joe assigned to a desk job in the Office of Naval Intelligence, in Washington, but his son refused. For months it had infuriated him that people were questioning the Kennedys’ courage, were leveling snide accusations against his father. How dare they? What did they know about bravery? He would prove them wrong by becoming a Navy flier. Joe Senior, knowing better than to stand in his proud son’s way, gave his blessing. “My father, especially, approves of what I’m doing,” Joe told the press, in a revealing exaggeration. “He thinks I’m doing what I should be doing, and he’s glad for it.” In late June, Young Joe was inducted, along with FDR’s youngest child, John, and several other would-be aviators from Harvard. They became seamen second class, at a pay rate of $21 per month. Joe’s physical examination at Chelsea Naval Hospital, in Boston, showed him to be in sterling physical shape—he stood five feet eleven and weighed a robust 175 pounds, and without a single blemish on his health record.61

Jack knew what he must do: he had to follow suit. He promptly volunteered for the Army Officer Candidate School, but failed the physical on account of his bad back. He then tried the Navy, with the same result. He vowed to press on, and in Hyannis Port that summer he embarked on an exercise regimen to strengthen his back, in anticipation of his next attempt to enlist. How effective the workouts were, he couldn’t tell, but he felt good overall, free to enjoy his favorite place and time: the Cape in the summer. An early highlight was the Fourth of July weekend—always a time of special celebration in the Kennedy household, with a festively decorated porch and a long wooden table piled high with summer delicacies. The scene was frenetic as always, and filled with laughter. Jack and his siblings loved it, but on this holiday their father found himself worrying that his worst fears were coming true: a war he detested was drawing ever closer to America, and one son had already enlisted, with a second determined to join him. Fifteen-year-old Bobby was not too far behind, and Kick and Eunice were musing aloud about joining the Red Cross or even the Women’s Army Corps. If U.S. intervention came, Joe wondered, would there ever be another family gathering like this one?

There were more fun times in that sun-drenched Hyannis summer—the touch football games on the sloping lawn, the board games, the movie nights, the outings to Rexall’s for ice cream. Joe Junior was around a lot, commuting on weekends from his training base at Squantum, near Boston. Visitors came and went. Torby Macdonald showed up, which was unexceptional except that his letters to Jack, always playfully sarcastic, had of late taken on darker tones, the sarcasm more biting, more caustic, as though he resented Jack’s successes. The two also disagreed politically, with Torby espousing pro-appeasement and indeed even pro-German views.62 Lem Billings came, too, of course, as did John Hersey. Chuck Spalding, ever observant, marveled anew at the spectacle he had first encountered the summer before, one he found at once unique and quintessentially American. “It was a scene of endless competition, people drawing each other out and pushing each other to greater lengths. It was as simple as this: the Kennedys had a feeling of being heightened and it rubbed off on the people who came in contact with them. They were a unit.”63

That they were—an extraordinary constellation of eleven handsome and energetic people, close-knit and loving, protective of one another, living under one roof in the three-gabled house overlooking Nantucket Sound. But not for much longer. The patriarch was right to feel a sense of foreboding: that summer of 1941 would be the last time his family was all together.