January 25: “You will rejoice with us [that] Jack is being allowed to go out into this glorious sunshine today. We are so glad.”1

Mr. and Mrs. Kennedy, already frustrated by their second son’s lack of discipline, took a detached approach to the maladies, accustomed as they were to his constant trips to the infirmary. “What concerned us as much [as his ailments], or more,” Rose revealingly remarked years later, “was his lack of diligence in his studies; or, let us say, lack of ‘fight’ in trying to do well in those subjects that didn’t happen to interest him.” Whereas Joe Junior breezed along, having “no trouble at all” operating within Choate’s tightly regulated system, “Jack couldn’t or wouldn’t conform. He did pretty much what he wanted, rather than what the school wanted of him.”2

Her husband tried to gently curb the boy’s careless ways. In April 1932 he wrote:

In looking over the monthly statement from Choate, I notice there is a charge of $10.80 for suit pressing for the month of March. It strikes me that this is very high and while I want you to keep looking well, I think that if you spent a little more time picking up your clothes instead of leaving them on the floor, it wouldn’t be necessary to have them pressed so often. Also, there are certain things during these times which it might not be a hardship to go without, such as the University hat. I think it would be well to watch all these expenditures in times like these, in order that the bills will not run too high.3

With Jack’s grades sinking fast in the spring of 1932, especially in French and Latin, Cappy Leinbach instituted a strict new regimen whereby Jack had to repeat to him his French and Latin vocabularies every evening and could not leave his room during study period. The two also worked together on algebra. Leinbach assured headmaster George St. John that he was doing all he could to help his immature—though undeniably likable—young charge: “What makes the whole problem difficult is Jack’s winning smile and charming personality. I have to literally stifle an impulse to rebuke him with a grin, for he does meet each challenge with the most absurd and yet ingenious pretexts for not doing what is expected….The inescapable fact [is] that his actions are really amusing and evoke real hilarity.” Among other high jinks, the boy stole a life-size cardboard cutout of Mae West from the Wallingford cinema and slipped it into his bed, much to Leinbach’s shock during room inspection the next morning.4

Then again, the room inspection was often frustrating for the former military man. “Whenever Jack wants a clean shirt or a suit,” Leinbach reported to St. John, “it is necessary for him to pull every shirt or suit out of the drawer or closet, and then he does not ‘have time’ to put them back. His room is inspected night and morning every day, and I always find the floor cluttered up with articles of every description. When he sees me enter the room, he will at once start to put everything in order. He does it willingly and often remarks, ‘I never get away with anything in this house!’ ”5

Leinbach’s prodding no doubt helped prevent more serious disciplinary problems, but failed to turn the young pupil into an academic success, despite periodic predictions that a breakthrough was imminent. In May 1932, after Clara St. John relayed Rose Kennedy’s request that Jack not be forced to have a summer tutor (with Teddy having just been born, she had nine kids to care for, and said she could not also oversee a tutor arrangement), director of studies Frank Wheeler replied, “Jack Kennedy has a high IQ, and is one of the most undependable boys in the third form….I don’t see how we can by any means guarantee he won’t have to have a tutor. We could relieve her of all worry if she would send him to the summer session.”6

The headmaster appealed accordingly to Joe and Rose, and they agreed to enroll Jack in summer session, in order to “make up his deficiencies” from the first year. He did the required remedial work, but no more. (At session’s end, his algebra teacher complained of his sloppy habits in the subject and his “careless attitude toward academic work in general.”)7 Jack’s well-established willingness to settle for the minimum passing grade, and to wait until the last possible moment to study for a test, remained intact through all four years at the school, and he racked up one middling grade after another. His Latin score went from 62 at the end of the first year to 69 at the conclusion of the second, whereupon he could mercifully end his longtime struggle with the language.* Four years of French yielded a cumulative average of 67. (“There is actually very little except physical violence that I haven’t tried,” his exasperated French teacher reported to the headmaster at the end of the first year. “His papers are chaotic, and he invariably forgets books, pencil, or paper.”) In math, he mustered a 69.67. Chemistry and biology bored him. Even in English and history, his preferred subjects, he hardly blazed a trail, usually scoring in the seventies and low eighties. His final rank at the school placed him sixty-fifth in a class of one hundred ten.8

Of course, such metrics hardly ever tell the full story, confusing as they do motivation and diligence with aptitude. Jack Kennedy’s teachers, like those at his previous schools, saw his potential, his intelligence, his way with words, his ability to absorb information quickly and accurately from the printed page. Harold L. Tinker, his fifth-form English teacher, gave Jack a low overall grade but thought highly enough of his papers to conclude that he was a gifted writer, who made up for his poor spelling and erratic punctuation with an exceptionally good vocabulary and who ought to consider a literary career.9 Tinker also found that Jack, when engaged, often grasped the insights of a novel or a poem—he was partial to Robert Frost—more fully than his classmates, and he was impressed by the young man’s expansive knowledge of world affairs. History teacher Russell Ayers remarked in the fall of 1933 that Jack possessed “one of the few great minds” he had ever had in history class. Teachers and friends alike noted his interest in, and knowledge of, diplomatic history and contemporary world affairs, as well as his excellent memory, which enabled him to recite poems at considerable length. Courteney Hemeney, who taught English and history, later said of Jack that “he understood the reading even when he hadn’t read it and always wrote fluently and incisively.” And, though he was “not as steady as his brother Joe, there were flashes of brilliance.”10

Such evidence of Jack’s potential only frustrated Joe Kennedy, whose concern was his second son’s insouciance and lack of application. He poured out his worries in a letter to St. John in the late fall of 1933, soon after visiting the school and seeing Jack play in a football game. Things had reached “a very critical stage,” Kennedy wrote, and Jack “certainly is not on the right track. The observations that I made [in speaking with Jack] are not much different than I made before, that the work he wants to do he does exceptionally well, but he seems to lack entirely a sense of responsibility, and that to my way of thinking must be developed in him very quickly, or else I am very fearful of the results.” Feeling the need to underscore the point, Kennedy added, “The happy-go-lucky manner with a degree of indifference that he shows towards the things that he has no interest in does not portend well for his future development.” But hope was not lost: “I feel very, very sure that if responsibility can be pushed on his shoulders, not only in his studies but in other things, that he may decide to observe them. He has too many fundamentally good qualities not to feel that once he got on the right track he would be a really worthwhile citizen.”11

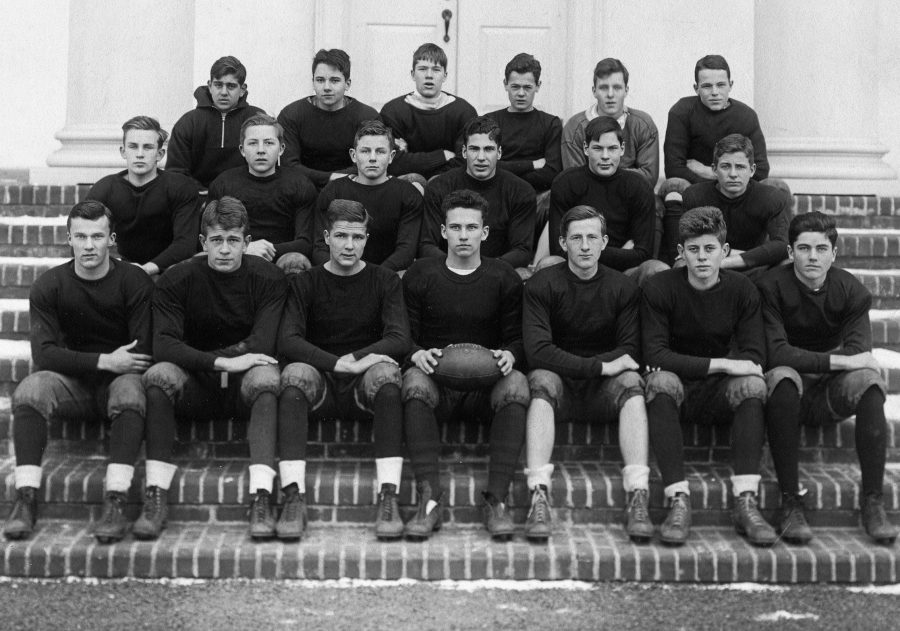

The Choate junior football team, fall 1933. Jack is in the first row, second from right.

St. John got Kennedy’s permission to share and discuss the letter with Jack. The conversation was productive, the headmaster reported to Kennedy, and he saw little reason for deep concern: “The fact of the matter is that I cannot feel seriously uneasy or worried about Jack. The longer I live and work with him, and the more I talk with him, the more confidence I have in him. I would be willing to bet anything that within two years you will be as proud of Jack as you are now of Joe.”12

II

In one essay that year, Jack pondered how a Christian God could allow evil in the world, and how true justice could be achieved when people were born into such widely varying circumstances. Does God in fact “render to everyone his just due,” Jack asked, given the vast disparities in the human condition?

A boy is born in a rich family, brought up in [a] clean environment with an excellent education and good companions, inherits a fool-proof business from his father, is married and then eventually dies a just and honest man. Take the other extreme. A boy is born in the slums, of a poor family, has evil companions, no education, becomes a loafer, as that is all there is to do, turns into a drunken bum, and dies, worthless. Was it because of the [rich] boys abylity that he landed in the lap of luxery, or was it the poor boys fault that he was born in squalor? The answer will often come back “The poor boy will get his reward in the life hereafter if he is good.” While that is a dubious prospect to many of us, yet [there is] something in it. But how much better chance has [the] boy born with a silver spoon in his mouth of being good than the boy who from birth is surrounded by rottenness and filth. This even to the most religious of us can hardly seem a “square deal.” Thus we see that justice is not always received from “The Most Just” so how can we poor mortals ever hope to attain it.

The young Kennedy, himself a son of privilege, was professing here that he saw little reason why the less fortunate should put much stock in the traditional Christian promise of a heavenly reward for a life well lived. Maybe such a reward would indeed be forthcoming, he allowed, but inequalities of condition and opportunity made the task of living a morally upright life much more daunting for those born into poverty and despair. In sum, injustice in the world remained a problem for which the Bible offered few answers.13

It was a core philosophical position, staked out at sixteen, in the midst of the Great Depression, from which the grown-up Jack Kennedy—congressman, senator, president—would never waver.

Kay Halle, a wealthy socialite friend of Joe Senior’s, got a sense of Jack’s precocity when, accompanied by the father, she visited him in a hospital room where he was laid up with one malady or another. It was her first encounter with him, and it made an impression. “Jack was lying in bed, very pale, which highlighted the freckles across his nose. He was so surrounded by books I could hardly see him. I was very impressed, because at that point this very young child was reading The World Crisis, by Winston Churchill.” Halle did not indicate whether Jack had all six volumes of this epic mega-history of World War I in the hospital room that day, and one wonders, too, what he made of Churchill’s interpretation of the war, so different from his father’s. Whereas the elder Kennedy still clung to his view that the Great War had been a colossal waste, sacrificing millions of young men for no good reason, Churchill, though critical of many aspects of British and Allied strategy, extolled leaders and fighting men who set duty and sacrifice before self-interest, who were driven by something bigger than themselves, and whose cause was entirely just: “Every man a volunteer, inspired not only by love of country but by a widespread conviction that human freedom was challenged by military and Imperial tyranny.”14

Author Barbara Leaming suggests that Jack’s reading of The World Crisis initiated his lifelong fascination with and admiration for Churchill (later in adolescence he read and loved the Englishman’s massive million-word biography of Marlborough, the great military commander, statesman, and Churchill ancestor) and also spurred a deep and lasting interest in the question of how wars begin—and how to prevent them.15 This seems right, and there can be no doubt that, given his growing interest in international affairs, Jack in this period followed current global politics as well—the climb to power in 1933, during his second year at Choate, of Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist Party in depression-ravaged Germany; the deepening crisis of confidence in France and Britain; and the growing tensions in East Asia as a rising Japan flexed its muscles.

With respect to domestic affairs, on the other hand, including the widespread dislocation and deprivation caused by the Great Depression, one doesn’t see the same level of engagement from young Jack—notwithstanding his probing fifth-form paper on injustice. To a considerable extent, the cloistered Choate existence kept the students isolated from the outside world. Then again, from his daily New York Times Jack would have been aware of the devastating effects of the economic downturn on his fellow Americans. Given his superior recall, he might even have known some specifics: that between 1929 and 1933, the gross national product declined by half; that 100,000 businesses in that period shut their doors; that corporate profits fell from $10 billion to $1 billion; that by the time of the presidential election of 1932, a quarter of the nation’s workforce was unemployed, while millions more worked only part-time; and that there was no national safety net: no unemployment compensation, no welfare system, no social security.

On home visits, too, Jack would have observed up close his father’s deepening gloom over the state of the nation. This was something new, for over the previous dozen years Joe Kennedy had shown scant sustained concern about political developments—he’d been too busy making money and producing movies. Even the historic candidacy of fellow Catholic Alfred E. Smith, the Democrats’ choice for president in 1928, had failed to excite him. Although still a Democrat by party affiliation (if more from inheritance than conviction), Kennedy had profited handsomely from the “Coolidge prosperity” of mid-decade, and he had felt strongly that Herbert Hoover stood a better chance than Al Smith of keeping the good times going. (He may also have been embarrassed by the informality of Smith’s campaign style, adhering in core respects to the stereotype of the crude Irish pols of Joe’s Boston youth.)16

The stock market crash and subsequent Depression changed him. Though his vast fortune remained intact and indeed grew, thanks to his expertly timed withdrawal from the stock market prior to the crash and his adept short selling afterwards (in 1935 his wealth would be estimated at $180 million, or $3.6 billion today), he now saw the future in bleak, self-centered terms, fearing a radical upheaval that might bring down the social and economic order and scuttle everything he had built for his family. His political philosophy, such as it was, remained inchoate and cynical—basically, acquiring and maintaining power were all that really mattered—but he intuited that whereas in the twenties business had been supreme, the thirties would be the decade of government, with the reformers running the show, and that he needed to shift his attention accordingly. He saw the limits of his long-held belief that money brought power; real power, he now saw, rested in politics.17

Kennedy hitched his hopes to one man, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the governor of New York and Democratic candidate for president in 1932. The history between the two men reportedly went back to World War I, when, as manager of the Fore River shipyard, Kennedy negotiated testily with Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the Navy, over the fate of two Argentine dreadnoughts completed before the war but returned to the Fore River yard for premature repairs. (Kennedy, so the story goes, refused to deliver the vessels until payment was received; Roosevelt objected and, when Kennedy stood firm, dispatched Navy tugs to tow away the ships.)18 Now, a decade and a half later, Kennedy, having seen up close the flaws in the economic system that had made him rich, willed himself to believe that Roosevelt, more than the ineffectual Hoover, represented capitalism’s best hope against revolution from below. And there was cold opportunism, too: Kennedy speculated that FDR would win and that through him he might himself find an entrée into politics. Roosevelt, for his part, saw in Kennedy not only a means of building up his presidential war chest, but a rare and formidable ally in the world of finance.19

“Roosevelt was a man of action,” Kennedy told a journalist later. “He had the capacity to get things done….Long before the campaign, long before his name was even seriously considered, I went out to work for him. I think I was the first man with more than $12 in the bank who openly supported him. I did this because I had seen him in action. I knew what he could do and how he did it, and I felt that after a long period of inactivity we needed a leader who would lead.” To another reporter he said, “I wanted [Roosevelt] in the White House for my own security and for the security of our kids, and I was ready to do anything to elect him.”20

They were a fascinating pair, so similar in some ways, so contrasting in others. Both were intelligent and egotistical men, skilled in the art of concealing their true motives behind guileless masks. Both were impatient with intellectual debate over abstract ideas and theories. (At Harvard, where they were eight years apart, they had been content to scrape by in their classes and to prioritize the social dimensions of collegiate life.) Both were hearty and outgoing, adept at attracting talented and dedicated subordinates, yet were not known for maintaining deep friendships—or being true to their wives. The differences were equally telling. Where Kennedy was fervent and single-minded, Roosevelt was cool and urbane, content to operate on myriad levels at once. Kennedy viewed the human condition in dark, fatalistic terms, whereas Roosevelt usually saw reasons for optimism even in the most difficult circumstances; he had the greater faith in the power of democratic ideals. Kennedy’s intellect, though formidable, had a narrow character, and he was uncomfortable with doubt; Roosevelt, with his more capacious sensibility, liked to entertain differing points of view. Most striking of all, whereas for Kennedy his children were always supreme, Roosevelt seemed at times more responsive to his constituency—his “national family”—than to his own offspring.21

Thus began a marriage of convenience, one that was never free of mutual suspicion but that for a time, in the early and mid-1930s, also featured a degree of affection, or at least commonality based on a shared sense of humor and an appreciation of each other’s talents and achievements. Kennedy poured money and time into Roosevelt’s campaign in 1932, contributing ideas to the candidate’s speeches on the economy and calling wealthy Democrats to urge them to make donations. He also helped persuade newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst to break the deadlock at the Democratic National Convention that threatened an early FDR win. Kennedy then accompanied the candidate on a whistle-stop train tour to the western states in September, voicing robust support as Roosevelt called for greater government involvement in combating the economic crisis through “a new deal for the American people.” On election night, Kennedy put on a lavish victory party that took up two floors of the Waldorf Astoria, in New York, with Roosevelt’s theme song “Happy Days Are Here Again” blaring through the night. In the weeks thereafter, he laid on the flattery: in one telegram he informed FDR that a nun at his daughter Rosemary’s convent school had declared the new administration to be “like another Resurrection.” (Roosevelt, perhaps recalling what had occurred immediately before the previous Resurrection, replied vaguely with a thank-you for the “awfully nice telegram.”)22

There had been signs during the campaign of what would become two pronounced features of Joe Kennedy’s public persona in the years to come: his cultivation of the press and an obsessive interest in image-building. The right sort of publicity, his Hollywood years had taught him, could endow a person with fame as well as prestige; consequently, he made friends among the reporters who covered Roosevelt and took every chance to chat them up. “He liked being with the press more than he liked being with the politicians,” said Ernest Lindley, a correspondent who two years earlier had penned the first Roosevelt biography. “He liked the repartee.”23

Kennedy hoped to be appointed secretary of the Treasury in the new administration, but, to his intense frustration, there would be no offer of any kind for more than a year after the inauguration, in large part because of opposition at the White House, especially from the gnarled, gnomish, chain-smoking chief secretary, Louis Howe, who loathed the idea of bringing on a man he considered an unscrupulous Wall Street denizen. His pride wounded, Kennedy turned privately critical of Roosevelt—in letters, phone calls, and face-to-face meetings, he unloaded on FDR for his ingratitude and callousness—only to fall under the spell of the president’s mesmerizing charm whenever they met and leave each encounter pledging his undying support. In 1934, after being passed over a second time for the Treasury slot and turning down an offer to become the U.S. representative to Ireland, he agreed to head up the Securities and Exchange Commission, a newly created entity designed to regulate stock exchanges, meaning that the notorious stock speculator would now be the cop on Wall Street’s corner.24 Presidential aides objected to the appointment for that reason, but Roosevelt held firm. Set a thief to catch a thief, he reasoned.25