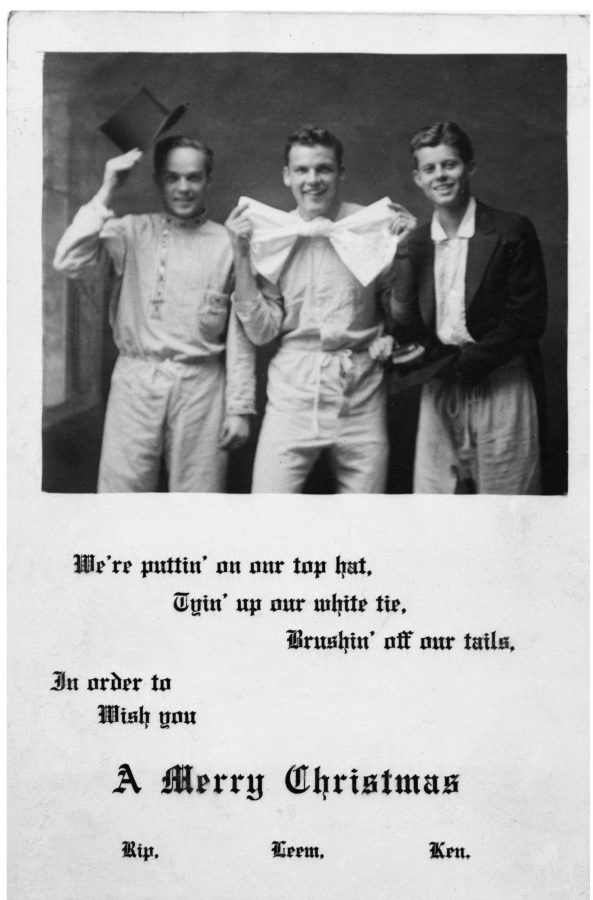

A 1935 Christmas card from three Princeton roommates, with a greeting inspired by the lead song in the new Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers film, Top Hat: Rip [Ralph Horton], Leem [Lem Billings], and Ken [Jack].

And thus ended Jack Kennedy’s tenure as a Princeton man, six weeks after it began. He would not return. The prospect of being laid up in Boston seemed dreadful, but he couldn’t quibble with his father’s argument that it was imperative “to arrive at a definite conclusion regardless of how much time it takes because we must settle this matter once and for all on this occasion.” The physicians got to work. “They are doing quite a number of things,” the young patient wrote his parents from his hospital bed, “but I am rather a difficult subject.”26 A flood of letters to Billings followed—witty, obscene, uninhibited, gossipy, unflappable, and suffused with a striking vitality that his mother had noticed in his language ever since he was a small child.

January 18, 1936: “My blood count this morning was 3500. When I came it was 6,000. At 1500 you die. They call me ‘2,000 to go Kennedy.’ ”27

January [undated]: “[It is] the most harrowing experience of my storm-tossed career. They came in this morning with a gigantic rubber tube. Old stuff, I said, and I rolled over thinking it would be stuffed up my arse. I didn’t know whether they thought my face was my ass or what but anyway they shoved it up my nose and down into my stomach. Then they poured alcohol down the tube, me meanwhile going crazy as I couldn’t taste the stuff and you know what a good stiff drink does to me.”28

January 27: “They haven’t told me anything, except that I have leukemia, and agranalecencytosis [presumably he meant agranulocytosis, a rare blood disorder]. Took a peak [sic] at my chart yesterday and could see that they were mentally measuring me for a coffin. Eat, drink, and make Olive [Cawley], as tomorrow or next week we attend my funeral.”29

January 27: “Flash! Got the hottest neck ever out of Hanson Saturday night. She is pretty good so am looking forward to bigger and better ones. Also got a good one last night from J. so am doing you proud. Gave up Bunny Day, I must admit, as a failure.” (In an earlier letter he had boasted that he would soon “climb” her “frame.”)30

Though playful in these missives, Jack could be cruel toward Lem in a way that betrayed his sense of entitlement. “I don’t know why you and Rip are so unpopular with girls,” he scoffed in one, signing off with one of his nicknames: “You’re certainly not ugly looking exactly. I guess they’re [sic] is just something about you that makes girls dislike you on sight. I was figuring it out this morning….It certainly is too bad. I guess you are just not cut out to be a ladies man. Mr. Niehans even has a girl, and so has Ike England. Frankly, my son, I’m stumped. Well send me my belt you prick right away, Regards, Ken.”31

Yet there was a tenderness in the letters, too, a vulnerability that Jack hated to reveal but that Billings undoubtedly picked up on, however couched it was in Kennedy’s devil-may-care personal style. Still smitten with Olive Cawley, who had been named the first Peanut Festival Queen in Montclair, New Jersey, and was about to embark on a modeling career in New York, he asked Lem for help: “Am coming to you for advice on the Cawley situation—should I ask her after this deliberate slight?” (Olive had not replied to his most recent letter.) “It’s your roomie who is asking and he’s also asking you to leave my writing paper alone. That writing paper was a present from one of my feminine admirers, a woman who worships the very air I breathe,” he said of Mrs. Billings, “but who unfortunately has a son with bad breath.” The barb no doubt stung the easily wounded Billings, but he always sensed his friend’s underlying devotion to him. Rip Horton saw this side of Jack, too. “[He] was very light, very witty, a particularly loyal good friend who cherished old friendships very, very much,” Rip subsequently said. Sometimes, Horton added, Jack went to greater lengths to maintain the relationships than the friends did.32

Lem offered his own assessment: “I think it’s interesting,” he told an interviewer, “because I, frankly, haven’t had another friend whom I’ve known as long as Jack Kennedy….There must have been something about him that kept people wanting him to be their friend through all the years. Much more interesting is why Jack wanted to keep all these friends, since his mind and interests did grow, let’s face it, at a much faster clip than any of his contemporaries.”33

When Billings forfeited his scholarship at Princeton due to poor grades, Jack was quick to offer his sermonizing take. “It’s too damn bad about losing your scholarship,” he lectured, “but here is my advice. You have been a damn fool—spending money you didn’t have, taking week-ends you shouldn’t have, and generally fooling around.” Jack did not deny that he was partly to blame, but he admonished his friend that only hard work could salvage the situation. “If you decide to go on a vacation you can come [to Palm Beach] as we have plenty of room. However, you have been a terrific ass, and unless you come around now, you haven’t a chance. If you do good work now, maybe you can get the scholarship back.”34

The exhortation worked; Lem put in the necessary effort to reclaim the scholarship.

Beyond the misdiagnosis of leukemia, the Boston doctors reached no conclusions, and in February 1936 Jack was dispatched to Palm Beach to convalesce. His father was there, still waiting to be tapped for a major job within the Roosevelt administration. He had concluded a successful tenure as head of the Securities and Exchange Commission and hoped now to get a bigger role—a cabinet position, certainly, and ideally Treasury secretary. Roosevelt’s shift to the left in 1935—he created the Works Progress Administration, a massive employment and infrastructure program, and signed into law the Social Security Act—did not concern Kennedy, or if it did he refrained from saying so. On the contrary, he paid Arthur Krock of The New York Times $5,000 to gather together scattered notes into a short book with a snappy title, I’m for Roosevelt, that offered a rich man’s fawning endorsement of the New Deal and a second FDR term and would be published under Kennedy’s name in time for the 1936 presidential election. Businessmen should be grateful to Roosevelt for saving capitalism, the book argued, and it credited the president for every economic advancement since 1933.35

To head off complaints that the book was a mere attempt at gaining a senior post in Washington, Kennedy included a humble and disingenuous disclaimer at the outset: “I have no political ambitions for myself or my children and I put down these few thoughts about our President, conscious only of my concern as a father for the future of his family and my anxiety as a citizen that the facts about the President’s philosophy be not lost in a fog of unworthy emotion.”36

Barely had Jack arrived in Florida when his father determined that he needed fresh air and physical labor to build up his strength. (Jack had other ideas: “The girls are few and far between,” he lamented to Billings early on, “but speaking of between, I expect I shall get laid shortly.”) On Krock’s recommendation, he arranged for his son to travel to the Jay Six Cattle Ranch, in Benson, Arizona, for several weeks of hard work in warm weather. It was a dramatic change for the East Coast urbanite, but the labor—making adobe bricks, rounding up cattle, fixing fences—seemed to have its desired effect.37 Jack’s health improved dramatically, and he soon found time for extracurricular adventures across the border in Nogales. “Got a fuck and suck in a Mexican hoar-house [sic] for 65¢, so am feeling fit and very clean,” he reported to Billings in a letter entitled “Travels in a Mexican Whore-house with Your Roomie.” He enthused, “What a thing of beauty my body has become with the open air, riding horses and Mexicans.”38

One detects more than a bit of artistic license in these carnal boasts as our protagonist works to project an image of macho health—vigorous, outdoorsy, athletic, virile—that stands in contrast with the more fragile reality. “I think he was making it up,” one college friend later said of the sexual bragging of this period in the mid-1930s. “That was the masculine ethic. And I think he made up three-quarters of it. And I don’t hold it against him.” Jack was telling his friends, telling himself, what kind of man he sought to be and could be. He projected an image of himself as a lothario well before he actually became one.39

Before returning to the East Coast, Jack headed for Hollywood, where he claimed he met and bedded a gorgeous movie extra. “The best looking thing that I have seen,” he bragged to Lem. “I will show you her picture when I get in.”40 There followed a summer in Hyannis Port filled with fun and frolic with the rest of the Kennedy clan—Joe Junior, 21, Rosemary, 17, Kathleen, 16, Eunice, 15, Pat, 12, Bobby, 10, Jean, 8, and Teddy, 4—and a stream of visitors, who as always looked with astonishment at the packed event schedule and manic family energy. Relatives came, too, including the three children of Rose’s sister Agnes and her husband, Joseph Gargan: Mary Jo, Joey, and Ann. (Agnes would die suddenly of an embolism in September, at age forty-three; in subsequent years, the Gargan kids would spend their summers on the Cape, effectively raising the size of Joe and Rose’s brood to an even dozen.) If Jack did not hold quite the esteem in his younger siblings’ eyes that the mature and responsible Joe Junior did, he had their affection for his witty individualism and for the attention he paid to them—not least Rosemary. As Eunice remembered, he quietly made sure his mentally challenged sister was not left out at parties: “Jack would take her to a dance at the club, and would dance with her and kid with her and would make sure a few of his close pals cut in, so she felt popular. He’d bring her home at midnight. Then he’d go back to the dance.”41

Much time was spent on the water that summer, in innumerable sailing competitions. Together Joe Junior and Jack raced from Edgartown, on Martha’s Vineyard, to Nantucket and back to Hyannis Port. At the end of August, Jack won a major solo race, the 1936 Atlantic Coast Championships, with a margin of victory—four minutes—that astonished other sailors. No doubt it helped that the ever competitive Joseph P. Kennedy employed a Scandinavian maintenance expert that summer to look after the family’s boats in order to make sure each was in tip-top racing shape.

Jack also found time to do something else: reapply to Harvard. He preferred it over the smaller, more cloistered Princeton, he had decided, and it was where his father always wanted him to go. Young Joe, too, urged him to join him in Cambridge. Now entering his third year, Joe had experienced disappointments at Harvard—he’d been passed over by the elite final clubs and had yet to find glory on the football field—but he liked his courses in government and had a coterie of friends who appreciated his endless energy and ebullience. Women were a preoccupation and, following his father’s example, he played the field with abandon, preferring showgirls over coeds. (The former were less likely to latch on, he said, less likely to make demands.) On one occasion he escorted to a Harvard dance the budding film star Katharine Hepburn, who accepted his invitation on the condition that her mother also join.42

Jack wrote from Hyannis Port on July 6:

Gentlemen, I am writing in regard to my entering Harvard this fall, in the class of 1940. I presented an application to enter Harvard…last year to enter with the class of 1939 which was accepted. My plans changed, and I decided to go abroad to the London School of Economics for a year….After my return from [Florida] I went out to Arizona returning a week ago. After seeing my physician who said he thought it would be perfectly all right for me to attend college next year, I decided to present my application to Harvard. If there is any other information desired, I should be glad to communicate with you or go to Boston to discuss the matter.43

To be on the safe side, Jack submitted a similar letter to Princeton. But within three days Harvard’s dean of freshmen replied with the good news: he was in.44 In his roundabout way, Jack had had what in today’s parlance would be referred to as a gap year between high school and college, and he arrived in Cambridge in August a year older than most freshmen and two years older than a few. He stood six feet tall and weighed 149 pounds, and felt as good as he had in years.

IV

The Harvard that Jack Kennedy entered in the fall of 1936 was still what it had been when his father matriculated three decades before, and when his great-grandfather Patrick Kennedy stepped ashore in nearby East Boston sixty years before that: the oldest, most richly endowed, and most prestigious university in the nation. Jack’s arrival coincided with the institution’s three hundredth anniversary and all the attendant celebrations. (On September 18, fifteen thousand alumni, including Franklin Roosevelt, joined delegates from five hundred universities around the world for a day of speeches and celebration in Harvard Yard.)45 But there was scant evidence of smug self-satisfaction that fall in the presidential office of James B. Conant. Since becoming Harvard’s leader three years before, Conant, a gaunt and bespectacled chemist whose descendants arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1637 but whose father was a lowly photoengraver from Dorchester, had set about making the institution more meritocratic, more academics-focused. His predecessor, the aristocratic and conservative A. Lawrence Lowell, had taken office in 1909, soon after Joe Senior matriculated, and over the next quarter century had done much to enhance Harvard’s architectural glories as well as its already robust reputation for exclusion: he set quotas on Jewish admissions, kept the small number of black freshmen out of Harvard dorms, and refused Marie Curie an honorary doctorate on account of her sex. When a senior professor was revealed to be a homosexual, Lowell not only demanded his prompt resignation but urged him to use a gun to “destroy himself.”46

Conant was no strict egalitarian, but he recognized that Harvard needed to change, needed to prioritize scholarly over social distinction. Rival institutions in the Midwest and California were on the rise, and it was no longer unheard of (if still rare) for major professors to turn down chairs at Harvard. Standards of faculty promotion were too lax, Conant determined, and the college was filled with “mediocre men” who were not doing first-rate original research. He set about toughening hiring and tenure standards for faculty and redressing what he saw as the “exclusively eastern orientation” of the student body (some 90 percent of the students came from states along the Eastern Seaboard) by offering Harvard National Scholarships to notably talented applicants from the Midwest and Far West who might not otherwise be able to afford the annual tuition of $400 or the additional $700 for room and board. “Many boys without financial resources are potentially future leaders of the professions, of business, and of public affairs,” Conant declared. “The country needs their talents and character.” Much to the delight of Irish, Italian, and Jewish day students from middle- or lower-class backgrounds who commuted by subway from their homes in greater Boston, he set aside the ground floor of Dudley House so that these boys would have somewhere to eat their brown-bag lunches.47

The journalist Theodore H. White, class of 1938 and one of the commuters, thrilled at Conant’s reforms. “Excellence was his goal as he began shaking up both faculty and student body,” White would recall in his captivating memoir In Search of History, before quoting approvingly from the president’s address to the freshmen in August 1934: “ ‘If you call everyone to the right of you a Bourbon and everyone to the left of you a Communist, you’ll get nothing out of Harvard,’ he said to us. And he went on to explain that what we would get out of Harvard was what we could take from it ourselves; Harvard was open, so—go seek.”48

All the same, college life went on much as it had before. Students continued, as always, to subcategorize themselves—no less under Conant than under his predecessors—and the hierarchies of privilege remained firmly in place. Theodore White identified three categories: white men, gray men, and meatballs. The white men were the “white shoe” prep school grads of prominent name—White’s own class contained two Roosevelts, a Hearst, a Rockefeller, a Morgan, a Saltonstall, and, a tad apart, a certain Joseph Kennedy Jr.—many of whom adhered to the timeworn maxim of the Harvard gentleman: “Three C’s and a D, and keep out of the newspapers.” The gray men were the products of public schools, “sturdy sons of the middle class.” They played football and baseball and hockey, edited the Crimson and the Lampoon, and ran for student government. (Among the gray men in White’s year was Caspar Weinberger, later to be Ronald Reagan’s secretary of defense.) At the bottom of White’s classification was his own group, the meatballs—scholarship boys and day students, many of them Italian, Jewish, or Irish. “We were at Harvard not to enjoy the games, the girls, the burlesque shows of the Old Howard, the companionship, the elms, the turning leaves of fall, the grassy banks of the Charles,” White wrote. “We had come to get the Harvard badge, which says ‘Veritas,’ but really means a job somewhere in the future, in some bureaucracy, in some institution, in some school, laboratory, university, or law firm.”49 For these students, social life at Harvard was a closed book—they emerged from the subway station in Harvard Square in the morning, went to class, and were whisked away on the evening train.

Within the groups could be found further distinctions. In Anton Myrer’s novel The Last Convertible, set in the same period, the blandly lovable narrator, George Virdon, a solidly middle-class product of a public high school who is at Harvard only because of a scholarship, describes the particular snobbery of the “St. Grotlesex” men—that is, the graduates of St. Mark’s, St. Paul’s, Groton, and Middlesex—who “by and large kept to themselves, dined and hung out at their exclusive final clubs, took a very casual attitude toward classes and grades, and very nearly constituted a college within the college. A Groton man sat next to me in a course on the Hapsburg Empire and never said a single word to me. Not one. It wasn’t that he cut me, exactly—I don’t think he ever even saw me. Some, like me, can accept it with equanimity and go their way. For others…it eats away at the vitals like acid: they may suppress it, but they never get over it.”50

A few students defied categorization. For White, the outstanding example in his class was the brilliant Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., whose father was on the faculty in history and who somehow mingled with the meatballs as easily as with the gray and white men. With his intellectual precocity and ravenous curiosity, Schlesinger asked only that people be interesting. “How could one not be friendly to dear Teddy White, himself the most loyal and sentimental of old friends?” Schlesinger wrote in his own memoirs of his friend’s description.51

Jack Kennedy likewise would skirt White’s taxonomy when he arrived at Harvard two years later. According to family wealth and academic pedigree, Kennedy should have been in the top group, but his private school, though prestigious, was not “St. Grotlesex.” (In Myrer’s formulation, the men from larger prep schools such as Andover, Milton, Exeter, and Choate were “better mixers” than those from St. Grotlesex, though they still tended to separate themselves from the groups below them.) More important, Kennedy was an Irish Catholic in what was still a bastion of WASP privilege. He, too, was a kind of outsider, and it generated in him a palpable detachment, an aloofness resulting from his uncertainty about where he really belonged. It also made him more accepting of other outsiders, of whatever stripe, made him inclined to take people for who they were. At Choate he had moved easily among boys from different backgrounds; his best friend, Lem Billings, was a middle-class scholarship student from Pittsburgh. At Harvard as well, Kennedy’s circle of acquaintances would be wide, even if made up mostly of gray men and white men. His best friend would be Torbert “Torby” Macdonald, himself a hybrid: a middle-class Irish Catholic from suburban Boston who had gone to Andover and who commuted from home his freshman year.