To begin with, they weren’t children at all. Not all of them, at least. There were small boys and big boys, fathers and grandfathers. Perhaps a few uncles too. And some of those people who live on their own on everybody’s road but don’t seem to have any relatives at all. They were everyone.

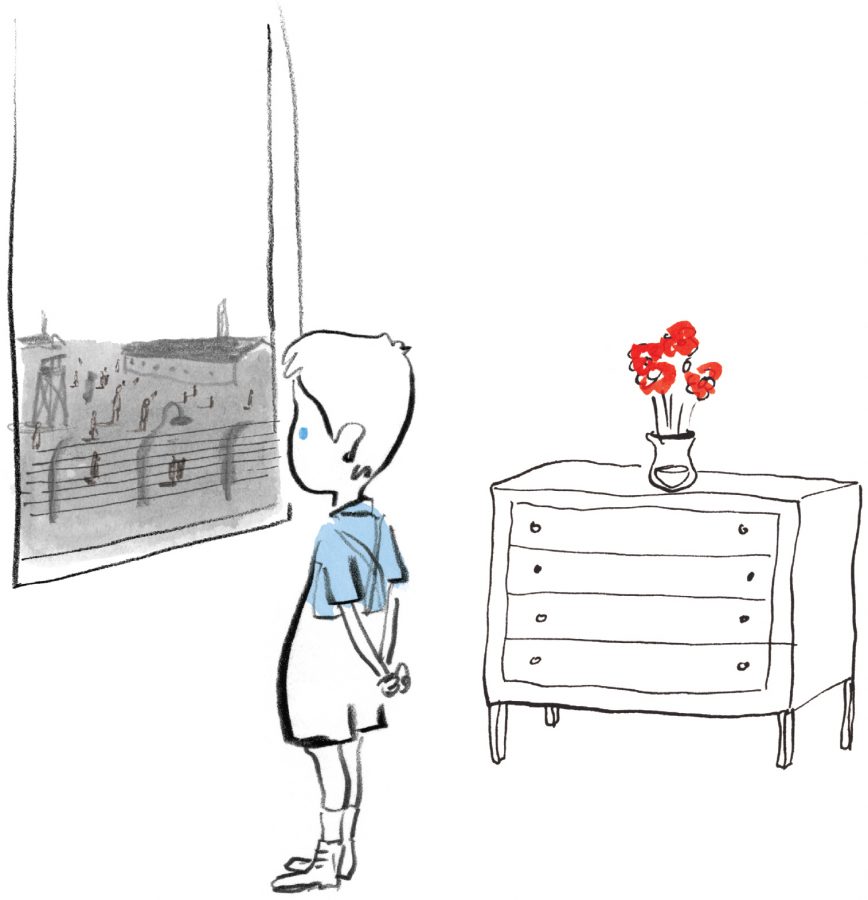

‘Who are they?’ asked Gretel, as open-mouthed as her brother often was these days. ‘What sort of place is this?’

‘I’m not sure,’ said Bruno, sticking as close to the truth as possible. ‘But it’s not as nice as home, I do know that much.’

‘And where are all the girls?’ she asked. ‘And the mothers? And the grandmothers?’

‘Perhaps they live in a different part,’ suggested Bruno.

Gretel agreed. She didn’t want to go on staring but it was very difficult to turn her eyes away. So far, all she had seen was the forest facing her own window, which looked a little dark but a good place for picnics if there was any sort of clearing further along it. But from this side of the house the view was very different.

It started off nicely enough. There was a garden directly beneath Bruno’s window. Quite a large one too, and full of flowers which grew in neat orderly sections in soil that looked as if it was tended very carefully by someone who knew that growing flowers in a place like this was something good that they could do, like putting a tiny candle of light in the corner of a huge castle on a misty moor on a dark winter’s night.

Past the flowers there was a very pleasant pavement with a wooden bench on it, where Gretel could imagine sitting in the sunshine and reading a book. There was a plaque attached to the top of the bench but she couldn’t read the inscription from this distance. The seat was turned to face the house – which, usually, would be a strange thing to do but on this occasion she could understand why.

About twenty feet further along from the garden and the flowers and the bench with the plaque on it, everything changed. There was a huge wire fence that ran along the length of the house and turned in at the top, extending further along in either direction, further than she could possibly see. The fence was very high, higher even than the house they were standing in, and there were huge wooden posts, like telegraph poles, dotted along it, holding it up. At the top of the fence enormous bales of barbed wire were tangled in spirals, and Gretel felt an unexpected pain inside her as she looked at the sharp spikes sticking out all the way round it.

There wasn’t any grass after the fence; in fact there was no greenery anywhere to be seen in the distance. Instead the ground was made of a sand-like substance, and as far as she could make out there was nothing but low huts and large square buildings dotted around and one or two smoke stacks in the distance. She opened her mouth to say something, but when she did she realized that she couldn’t find any words to express her surprise, and so she did the only sensible thing she could think of and closed it again.

‘You see?’ said Bruno from the corner of the room, feeling quietly pleased with himself because whatever it was that was out there – and whoever they were – he had seen it first and he could see it whenever he wanted because they were outside his bedroom window and not hers and therefore they belonged to him and he was the king of everything they surveyed and she was his lowly subject.

‘I don’t understand,’ said Gretel. ‘Who would build such a nasty-looking place?’

‘It is a nasty-looking place, isn’t it?’ agreed Bruno. ‘I think those huts have only one floor too. Look how low they are.’

‘They must be modern types of houses,’ said Gretel. ‘Father hates modern things.’

‘Then he won’t like them very much,’ said Bruno.

‘No,’ replied Gretel. She stood still for a long time staring at them. She was twelve years old and was considered to be one of the brightest girls in her class, so she squeezed her lips together and narrowed her eyes and forced her brain to understand what she was looking at. Finally she could think of only one explanation.

‘This must be the countryside,’ said Gretel, turning round to look at her brother triumphantly.

‘The countryside?’

‘Yes, it’s the only explanation, don’t you see? When we’re at home, in Berlin, we’re in the city. That’s why there are so many people and so many houses and the schools are full and you can’t make your way through the centre of town on a Saturday afternoon without getting pushed from pillar to post.’

‘Yes…’ said Bruno, nodding his head, trying to keep up.

‘But we learned in geography class that in the countryside, where all the farmers are and the animals, and they grow all the food, there are huge areas like this where people live and work and send all the food to feed us.’ She looked out of the window again at the huge area spread out before her and the distances that existed between each of the huts. ‘This must be it. It’s the countryside. Perhaps this is our holiday home,’ she added hopefully.

Bruno thought about it and shook his head. ‘I don’t think so,’ he said with great conviction.

‘You’re nine,’ countered Gretel. ‘How would you know? When you get to my age you’ll understand these things a lot better.’

‘That might be so,’ said Bruno, who knew that he was younger but didn’t agree that that made him less likely to be right, ‘but if this is the countryside like you say it is, then where are all the animals you’re talking about?’

Gretel opened her mouth to answer him but couldn’t think of a suitable reply, so she looked out of the window again instead and peered around for them, but they were nowhere to be seen.

‘There should be cows and pigs and sheep and horses,’ said Bruno. ‘If it was a farm, I mean. Not to mention chickens and ducks.’

‘And there aren’t any,’ admitted Gretel quietly.

‘And if they grew food here, like you suggested,’ continued Bruno, enjoying himself enormously, ‘then I think the ground would have to look a lot better than that, don’t you? I don’t think you could grow anything in all that dirt.’

Gretel looked at it again and nodded, because she was not so silly as to insist on being in the right all the time when it was clear the argument stood against her.

‘Perhaps it’s not a farm then,’ she said.

‘It’s not,’ agreed Bruno.

‘Which means this mightn’t be the countryside,’ she continued.

‘No, I don’t think it is,’ he replied.

‘Which also means that this probably isn’t our holiday home after all,’ she concluded.

‘I don’t think so,’ said Bruno.

He sat down on the bed and for a moment wished that Gretel would sit down beside him and put her arm around him and tell him that it was all going to be all right and that sooner or later they’d get to like it here and they’d never want to go back to Berlin. But she was still watching from the window and this time she wasn’t looking at the flowers or the pavement or the bench with the plaque on it or the tall fence or the wooden telegraph poles or the barbed wire bales or the hard ground beyond them or the huts or the small buildings or the smoke stacks; instead she was looking at the people.

‘Who are all those people?’ she asked in a quiet voice, almost as if she wasn’t asking Bruno but looking for an answer from someone else. ‘And what are they all doing there?’

Bruno stood up, and for the first time they stood there together, shoulder to shoulder, and stared at what was happening not fifty feet away from their new home.

Everywhere they looked they could see people, tall, short, old, young, all moving around. Some stood perfectly still in groups, their hands by their sides, trying to keep their heads up, as a soldier marched in front of them, his mouth opening and closing quickly as if he were shouting something at them. Some were formed into a sort of chain gang and pushing wheelbarrows from one side of the camp to the other, appearing from a place out of sight and taking their wheelbarrows further along behind a hut, where they disappeared again. A few stood near the huts in quiet groups, staring at the ground as if it was the sort of game where they didn’t want to be spotted. Others were on crutches and many had bandages around their heads. Some carried spades and were being led by groups of soldiers to a place where they could no longer be seen.

Bruno and Gretel could see hundreds of people, but there were so many huts before them, and the camp spread out so much further than they could possibly see, that it looked as though there must be thousands out there.

‘And all living so close to us,’ said Gretel, frowning. ‘In Berlin, on our nice quiet street, we only had six houses. And now there are so many. Why would Father take a new job here in such a nasty place and with so many neighbours? It doesn’t make any sense.’

‘Look over there,’ said Bruno, and Gretel followed the direction of the finger he was pointing and saw, emerging from a hut in the distance, a group of children huddled together and being shouted at by a group of soldiers. The more they were shouted at, the closer they huddled together, but then one of the soldiers lunged towards them and they separated and seemed to do what he had wanted them to do all along, which was to stand in a single line. When they did, the soldiers all started to laugh and applaud them.

‘It must be some sort of rehearsal,’ suggested Gretel, ignoring the fact that some of the children, even some of the older ones, even the ones as grown up as her, looked as if they were crying.

‘I told you there were children here,’ said Bruno.

‘Not the type of children I want to play with,’ said Gretel in a determined voice. ‘They look filthy. Hilda and Isobel and Louise have a bath every morning and so do I. Those children look like they’ve never had a bath in their lives.’

‘It does look very dirty over there,’ said Bruno. ‘But maybe they don’t have any baths?’

‘Don’t be stupid,’ said Gretel, despite the fact that she had been told time and time again that she was not to call her brother stupid. ‘What kind of people don’t have baths?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Bruno. ‘People who don’t have any hot water?’

Gretel watched for another few moments before shivering and turning away. ‘I’m going back to my room to arrange my dolls,’ she said. ‘The view is decidedly nicer from there.’

With that remark she walked away, returning across the hallway to her bedroom and closing the door behind her, but she didn’t go back to arranging her dolls quite yet. Instead she sat down on the bed and a lot of things went through her head.

And one final thought came into her brother’s head as he watched the hundreds of people in the distance going about their business, and that was the fact that all of them – the small boys, the big boys, the fathers, the grandfathers, the uncles, the people who lived on their own on everybody’s road but didn’t seem to have any relatives at all – were wearing the same clothes as each other: a pair of grey striped pajamas with a grey striped cap on their heads.

‘How extraordinary,’ he muttered, before turning away.