1942, Nazi-occupied France. Sandrine, a spirited and courageous nineteen-year-old, finds herself drawn into a Resistance group in Carcassonne – codenamed ‘Citadel’ – made up of ordinary women who are prepared to risk everything for what is right.And when she meets Raoul, they discover a shared passion for the cause, for their homeland, and for each other.But in a world where the enemy now lies in every shadow – where neighbour informs on neighbour; where friends disappear without warning and often without trace – love can demand the highest price of all…

CONTENTS

Dedication

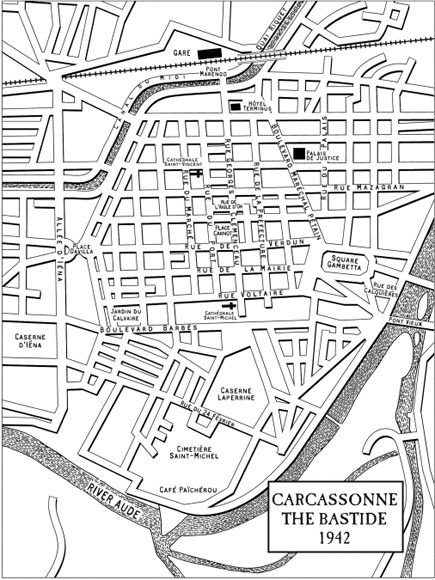

Maps

Principal Characters

Prologue

The First Summer

Codex I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Codex II

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Codex III

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Codex IV

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Codex V

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Shadows in the Mountains

Codex VI

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Codex VII

Chapter 54

Codex VIII

Chapter 55

Codex IX

Chapter 56

Codex X

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Codex XI

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Dedication

In memory of the two unknown women

murdered at Baudrigues

19 August 1944

Principal Characters

THE ‘CITADEL’ NETWORK

Sandrine Vidal

Marianne Vidal

Lucie Ménard

Liesl Blum

Suzanne Peyre

Geneviève Saint-Loup

Eloise Saint-Loup

IN CARCASSONNE

Raoul Pelletier

Robert Bonnet

Leo Authié

Sylvère Laval

Marieta Barthès

Jeanne Giraud

Max Blum

IN THE HAUTE VALLÉE

Audric Baillard

Achille Pujol

Erik Bauer

Yves Rousset

Guillaume Breillac

PROLOGUE

August 1944

COUSTAUSSA

19 AUGUST 1944

She sees the bodies first. On the outskirts of the village, a pair of man’s boots and a woman’s bare feet, the toes pointing down to the ground like a dancer. The corpses twist slowly round and around in the fierce August sun. The soles of the woman’s feet are black, from dirt or swollen in the heat, it’s hard to tell at this distance. Around them, flies cluster and swarm, argue, feed.

The woman known as Sophie swallows hard, but she does not flinch and she does not look away, returning to them a kind of dignity stolen by the manner of their death. She can’t risk going closer – it might be a trap, it looks like a trap – but from her hiding place in the undergrowth that marks the junction with the old road to Cassaignes, Sophie can see the victims’ arms are tied behind their backs with rough farm rope. The man’s hands are balled into fists, as if he died fighting. He has blue canvas trousers – a farmer or a refugee, not a partisan. The skirt of the woman’s dress lifts lightly in the breeze, a repeat pattern of lilac cornflowers on a pale yellow background. Sophie shields her eyes and follows the line of the rope, up through the dark green leaves of the old holm oak, to the branch that serves as the gibbet. Both victims are hooded, coarse brown hessian sacking, jerked tight by the noose and the drop.

She does not think she knows them, but she says a prayer all the same, to mark the moment of their passing. For the ritual of it, not out of faith. The myth of Christianity means nothing to her. She has witnessed too much to believe in such a God, such beautiful stories.

Every death remembered.

Sophie takes a deep breath, pushing away the thought that she’s too late, that the killing has already started. Crouched, she half runs, half crawls, hidden by the low, long wall that runs along the track down towards the village. She knows there’s a gap of fifteen feet, maybe twenty, between the end of the wall and the first outbuildings of the old Andrieu farm. No cover, no shade. If they are waiting, watching from the blackened windows of the house beside the abandoned cemetery, this exposed patch of land is where the bullet will find her.

But there’s no sniper, no one. She reaches the last of the capitelles, the ancient stone shelters that cluster in the hills to the north of Coustaussa, and slips inside. For some time, they used them to store weapons. Empty now.

From here, Sophie has a clear view of the village below, the magnificent ruins of the castle to the west. She can see that there’s blood on the whitewashed wall of the Andrieu house, a starburst of red, like paint splattered from a brush. Two distinct centres, blurred together at the edges, already turning to rust in the fierce afternoon sun. Sophie stiffens, though part of her hopes this means the man and woman were shot first. Hanging is the cruellest death, a slow way to die, degrading, and she’s seen this double execution before, once in Quillan, once in Mosset. Punishment and warning, the corpses left to the crows as on a medieval gallows.

Then she notices smudged tracks in the dirt at the base of the wall where bodies were dragged, and tyre marks that head down towards the village, not towards the holm oak, and fears this means two more victims.

At least four dead.

She suspects everyone has been taken to the Place de la Mairie while the soldiers search the farms and houses. Brown shirts or black, their methods are the same. Looking for deserters, for maquisards, for weapons.

For her.

Sophie scans the ground, looking for the glint of metal. If she can identify the casings, she can identify the gun and it might tell her who fired the shots. Gestapo or Milice, even one of her own. But she’s too far away and it looks as if the killers have been careful to leave no evidence.

For a moment she allows herself to sit back on her heels in the welcome shade, propped against the capitelle. Her heart is turning over, over in her chest, like the engine of an old car reluctant to start. Her arms are a patchwork of scratches and cuts from the gorse and hawthorn of the woods, dry and spiteful sharp after weeks of no rain, and her shirt is torn, revealing suntanned skin and the distinctive scar on her shoulder. The shape of the Cross of Lorraine, Raoul said. She keeps it covered. That mark alone is enough to identify her.

Sophie has cut her hair, taken to wearing slacks but, thin as she is, she still looks like a woman. She glances down at the boots on her feet, men’s boots held together with string and stuffed at the heel with newspaper for a less awkward fit, and remembers the cherry-red shoes with the little black heels she wore when she and Raoul danced at Païchérou. She wonders what’s happened to them, if they’re still in the wardrobe in the house in the rue du Palais or if someone has taken them. Not that it matters. She has no use for such luxuries now.

She doesn’t want to remember, but an image slips into her mind, of her own upturned face on the corner of the rue Mazagran, two years ago, looking up into the eyes of a boy she knew would love her. Then later that same summer, in her father’s study here in Coustaussa, and being told the truth of things.

‘And there shall come forth the armies of the air, the spirits of the air.’

Sophie blinks the memories away. She risks another look, peering out from the cover of the capitelle down to the cluster of houses and then up to the Camp Grand and the garrigue to the north. Having warned the villagers of the imminent attack, Marianne and Lucie have taken up position to the west, while Suzanne and Liesl will launch the main assault from the ruins of the castle. There’s no sign of anyone yet. As for the others promised, she does not know if they will come.

‘And the number was ten thousand times ten thousand.’

The beating silence hangs heavy over the waiting land. The air itself seems to vibrate and shimmer and pulse. The heat, the cicadas, the sway of the wild lavender and shock-yellow genet among the thistles, the whispering wind of the Tramontana in the garrigue.

For a moment, Sophie imagines herself back in the safe past. Before she was Sophie. She wraps her arms around her knees, acknowledging how appropriate it is that things should end here, back where it all began. That the girl she was, and the woman she has become, should make their final stand here together, shoulder to shoulder. The story has come full circle.

For it was here, in the narrow streets between the houses and the church and the ruins of the castle, she played trapette with the children of the Spanish refugees. It was here, in a green dusk heady with the scent of thyme and purple rosemary, she first kissed a boy. One of the Rousset brothers, fidgety in case his gran’mère should look out the window and catch him. An awkward meeting of teeth is what Sophie remembers. That, and the sense of doing something dark and illicit and adult. She closes her eyes. Yves Rousset, or was it Pierre? She supposes it doesn’t matter now. But it is Raoul’s face she sees in her mind’s eye, not the blunt features of a boy long dead.

Everything is so still, so quiet. Today, the swifts do not swoop and mass and spiral in the endless blue sky. The linnets do not sing. They know what is to come, they sense it too, in the same way, this past week, each of the women has felt the tension in the tips of her fingers, crawling over the surface of her skin.

Eloise was the first to be caught, five days ago, at the Hôtel Moderne et Pigeon in Limoux. Four days later, Geneviève was arrested in Couiza. The details of the boîte aux lettres, the fact that Sous-chef Schiffner was there himself, in person, left Sophie in no doubt the network had been betrayed. From that moment, she knew it was only a matter of hours, days at most. The spider’s web of connections that led south from Carcassonne to these hills, this river valley of the Salz, these ruins.

She tries not to think about her friends incarcerated in the Caserne Laperrine on the boulevard Barbès, or within the grey walls of the Gestapo headquarters on the route de Toulouse, fearing what they will suffer. She knows how long the nights can be in those dark, confined cells, dreading the pale light of dawn, the rattle of the key in the opening door. She’s drowned in choking, black water, submitted to the violent touch of hands on her throat, between her thighs. She’s heard the seductive whisper of surrender and knows how hard it is to resist.

Sophie rests her head on her arms. She’s so tired, so sick of it. And though she fears what is to come, more than anything now she wants it to be over.

‘Come forth the armies of the air.’

A burst of machine-gun fire from the hills, and the answering staccato chatter of an automatic weapon closer to hand. Sophie’s thoughts shatter, like fragments of bright glass. Already she’s up on her feet, pulling her Walther P38 from her belt, greasy with goose fat to stop the springs jamming. The weight of it in her hand is reassuring, familiar.

Breaking cover, she runs, low and fast, until she’s reached the edge of the Sauzède property. Once there were chickens and geese, but the animals are long gone and the door to the enclosure hangs open on a broken hinge.

Sophie vaults the low wall, landing on the remains of straw and uneven earth, then on to the next garden, zigzagging from one square of land to the next. She enters the village from the east, slipping through the unkempt cemetery, its gravestones like rotten teeth loose in the dry land. Crossing the rue de la Condamine, she darts into the tiny alleyway that runs narrow and steep and sheer along the side of the round tower and down, until she has a clear view of the Place de la Mairie.

As she’d suspected, the whole village has been brought there, beneath the burning sun. There is a Feldgendarmerie truck at right angles across the rue de la Mairie and a black Citroën Traction Avant, a Gestapo car, blocking the rue de l’Empereur, penning the villagers in. Women and children are lined up on the west side by the war memorial, the old men to the south of the small square. Sophie allows herself a grim smile. The configuration suggests they expect the attack to come from the hills, which is good. Then she sees a ribbon of red blood and the body of a young man lying on his back on the dusty ground, and her expression hardens. His right hand twitches and jerks, like a marionette on a frayed string, then falls back to his side.

Five dead.

Sophie can’t see who’s in charge – the line of grey jackets and black boots, the field greens of the ordinary soldiers, blocks her view – but she hears the order, given in French, that nobody else should move. Equipment is scarce, but these men are well armed, unusually so. Grenades at the waist, bandoliers slung over shoulders, glinting in the sun like chain mail, some with M40 sub-machine guns, the majority with Kar-98 semi-automatic rifles.

The hostages are caught between courage and common sense. They want to resist, to act, to do something, anything. But they’ve been told not to jeopardise the mission, and besides, they’re paralysed by the reality of the murdered boy on the ground in front of them. Someone – his mother, his sister – is sobbing.

‘C’est fini?’

Sophie can’t breathe. She is seeing everything, hearing everything, but can no longer take it in.

That voice.

The one person she’d hoped never to see again. The one voice she’d prayed never to hear again.

But you knew he would come. It’s what you wanted.

The rattle of a machine gun fired from the ruins of the castle snaps Sophie back to the present. Taken by surprise, one of the soldiers jerks round and returns random fire. He’s no more than a boy either. A woman screams and pulls her children to her, trying to shield them. Jacques Cassou, a Pétainist, though a good man at heart, breaks away from the group. Sophie can see what’s going to happen, but she’s powerless to stop it. She wills him to wait just a moment more, not to draw attention to himself, but panic has taken hold. He tries to run to the safety of the rue de la Condamine, forcing his tired, swollen legs to carry him away from the horror, but he’s an easy target. Sophie can only watch as the Schmeissers tear into the old man, the force of the assault spinning him round. His daughter Ernestine, a lumpen, bitter woman, runs forward and tries to catch him. But she is too slow, he is too heavy. Jacques staggers, drops to his knees. The soldiers keep firing. This second hail of bullets brings them both down.

Six dead. Seven.

The world breaks apart. The signal has not been given, but, hearing the guns, Marianne and Lucie launch the first of the smoke-signal canisters from the Camp Grand. It soars over the houses and lands at the edge of the square by the truck, disgorging a stream of green smoke. Another canister pops, then another and another, releasing plumes of blue and pink and orange and yellow into the stifling air. The soldiers are disorientated, cross-firing into one another’s positions. They, too, are on edge, Sophie realises. Whatever they’ve been told about this operation, they know something doesn’t add up. It is no ordinary raid.

‘Halten Sie! Halten!’

The Kommandant shouts the order to hold fire, then repeats it again in French. Discipline is restored immediately, but the hiatus is long enough for the hostages to scatter, as Marianne had told them to do, heading for refuge in the church, in the shaded undergrowth below the chemin de la Fontaine, the cellars of the presbytery.

Sophie does not move.

Now that the square is clear of civilians, Suzanne and Liesl launch the main assault from the ruins of the castle and the deep undergrowth that lines the rue de la Mairie. Bullets rake the ground. A grenade explodes instantly on impact with the war memorial.

Another order from the Kommandant, and the Gestapo unit divides into two. Some target the contingent in the hills, firing indiscriminately as they storm along the rue de la Condamine and out into the garrigue. The remainder turn towards the castle. Through the coloured smoke and the dust, Sophie glimpses the blue berets of the French Milice vanishing into the rue de la Peur and realises, with a sickened heart, that they do not mean to leave any witnesses alive.

She knows that she is outnumbered, at least seven to one, but she has no choice now but to show herself. Besides, she can see him, in plain clothes, standing with his right hand resting on the black bonnet of the car and his Mauser hanging loose in his left. He looks calm, disengaged, as the firefight rages around him.

Sophie drops the hammer on her pistol and steps out into the light.

‘Let them go.’

Does she say the words out loud or only in her head? Her voice seems to be coming from a long way away, distorted, a whispering beneath stormy waters.

‘It’s me you want, not them. Let them go.’

It’s not possible that he should hear her, and yet, despite the noise and the shouting and the ack-ack of the machine guns, he does. He hears her and he turns, looking straight to the north-east corner of the Place de la Mairie where she has positioned herself. Those eyes. Is he smiling, she wonders, or does it pain him that it should be ending like this? She can’t tell.

Then he says her name. Her real name. The soft music of it hangs suspended in the air between them. Threat or entreaty, she doesn’t know, but she feels her resolve weaken.

He says it again and, this time, it sounds bitter, false in his mouth. A betrayal. The spell is broken.

The woman known as Sophie lifts her arm. And shoots.

CHATEAU DE BAUDRIGUES

19 AUGUST 2009

On Wednesday morning at 9.20, people are gathering in the clearing at the Château de Baudrigues. Flags and a band, official colours and decorations and a sense of purpose.

The president of the delegation and the Mayor of Roullens are laying wreaths at the three gravestones: one for Jean Bringer – ‘Myriel’, one for Aimé Ramond; the last inscribed to the ‘Martyrs of Baudrigues’.

Men and women in their official sashes and chains remembering, on the sixty-fifth anniversary of their murders on 19 August 1944, those who gave their lives so that others might live. Also, representatives of the civilians massacred as the Germans left Carcassonne the following day.

The warrior stone angel – Y Penser Toujours – stolen away from Square Gambetta under cover of night so that it would not be destroyed. The statue stands, now, in the cimetière Saint-Michel, keeping watch over the military graves.

White crosses and white crescents.

The Martyrs of Baudrigues never got to see, only a few days later, the men and women of the Resistance come down from the hills and take possession of their town once more.

The Mayor steps back and everyone bows their head for the minute’s silence. A man in his sixties turns and puts his hand on his father’s shoulder. They are so alike, Max Blum and his son Jean-Jacques, people always remark upon it. Blum is well respected and well liked in Carcassonne. One of the last to be deported from Le Vernet on the ghost train to Dachau and one of the few to survive. Jean-Jacques’ three daughters all resemble their grandmother, Lucie Ménard. They never met her, though they have grown up their entire lives with stories of the sort of woman she was. They think their father and Tante Liesl exaggerate a little, but they play along all the same.

Jean-Jacques smiles at Liesl, Liesl Rousset, a celebrated war photographer. Even though his aunt is in her eighties, she is nonetheless the most beautiful woman he knows. Her children live overseas, as does she, but she has come home today for this modest ceremony and to visit her oldest friends, Marianne Vidal and Suzanne Peyre, who still live in the rue du Palais.

The sixty seconds of silence comes to an end and the band strikes up ‘La Marseillaise’.

At the back of the crowd, a young woman, named Alice, turns to her husband.

‘Can you take her, Will? I think she’s had enough.’

Will smiles and hoists their little girl on to his shoulders. So as not to disturb proceedings, he walks away into the deep green woods surrounding the park.

Alice moves closer to the front, singing the last few verses of the anthem in her undeniably English accent.

Amour sacré de la Patrie

Conduis, soutiens nos bras vengeurs

Liberté, Liberté chérie

Combats avec tes défenseurs!

She is not sure why she has come, other than because she believes Audric Baillard would have wanted her to. Or perhaps it is because, like many others, she has heard stories of a women’s resistance unit said to have single-handedly saved an entire village from being massacred in the dying days of the occupation. Their names don’t appear in any of the history books, but there’s something that makes Alice certain the stories are true.

Sous nos drapeaux, que la victoire

Accoure à tes mâles accents

Que tes ennemis expirants

Voient ton triomphe et notre gloire!

She wishes she had asked Monsieur Baillard about it, but they were caught up in a different story, in a different time. And the time they had together was so short.

There is a polite, awkward smattering of applause. The dignitaries start to leave – there is another event to be held in Carcassonne later in the day – and the small crowd of onlookers starts to break up.

Alice finds herself left alone with two women. One is elegant in blue, her white hair braided at the nape of her neck. The other is tall, with tightly cropped hair and a tanned face.

‘Are you a relative?’ she asks, peering at the names on the tombstone.

Marianne Vidal turns and looks at her, then smiles.

‘Our friend,’ she says, with a quiet dignity. ‘And my sister.’

‘What was she called?’ Alice asks quickly, wondering why their names are not on the memorial. There are only men’s names.

For a moment, she thinks the woman will not answer. Then a smile lights up her eyes.

‘Sandrine Vidal.’

At that moment, Alice’s daughter runs back into the clearing and into her mother’s arms. She scoops Sajhësse up and then turns to make the introductions.

But the two women, arm in arm, are already walking away.

PART I

The First Summer

July 1942

Codex I

GAUL

THE CARSAC PLAINS

JULY AD 342

The young monk looked across the river and saw the outline of the town ahead on the hill on the far side. A fortified castellum, the low walls sharply defined in the shimmering light of dawn. A crown of stone set on the green plains of Carsac. The slopes surrounding the settlement were abundant, rich, fertile. Row after row of vines, spread out like a peacock’s tail. Silver olive trees and heavy purple figs ripening on the bough, almond trees.

In the east, the white sun was rising in a pale blue sky. Arinius drew closer to the water’s edge. A low mist floated above the silver surface of the river Atax. To his right, wooded glades of elder and ash. The reed beds shifting, swaying, in the breeze. The distinctive silhouette of angelica, with its hollow fluted stems standing like soldiers to attention, the leaves as big as his hand. The familiar bell-shaped pink flowers of knitbone. The splash of fish and snakes, water boatmen skimming their silent way across the mirrored surface.

For week after week, one month, two months, the young monk had walked and walked and walked. Following the sweep and flow of the great Rhodanus from Lugdunum, south towards the sea. Rising before matins each day, with the memory of the gentle murmur of his brothers’ voices in his head, he voyaged on alone. In the heat of the day, between the hours of sext and nones, sheltering from the sun in the dense green woods or shepherds’ huts. In the late afternoon, as the first stirrings of vespers echoed from the chapel in the community, he would rise again and fare forward. The Liturgy of the Hours marking the progress of the days and nights. A slow and steady progress from north to south, from east to west.

Arinius didn’t know precisely how long he had been travelling, only that the seasons were changing, spring slipping softly into early summer. The colours of April and May, white blossom and yellow broom and pink phlox, yielding to the gold of June and July. The green vineyards of the Gallia Narbonensis and the sweep of barley in the fields. The driving wind whipping over the austere salt flats and the blue of the gulf of the Sinus Gallicus. That stretch of the journey followed the Via Domitia, the Roman wine route, along roads of tolls and taxes. It had been simple for him to blend in with the merchants and traders heading for Hispania.

Arinius coughed and pulled the grey hooded cloak tight around his narrow frame, though it was far from cold. The cough was worse again, leaving his throat raw. Bunching the material at his neck, he re-pinned his brooch. A bronze fibula, in the shape of a cross, with tiny white enamel oak leaves decorating each of the four arms and a green leaf in the centre. It was the only personal possession Arinius had been unable, unwilling, to give up on entering the community. A gift from his mother, Servilia, the day the soldiers came.

He looked across the Atax to the walls of the town and gave thanks to God for his safe deliverance. He had heard that here, men of all faiths and creeds were given sanctuary. That here, Gnostics and Christians and those who adhered still to the older religions lived side by side. That this was a place of safety and refuge for any and all who would come.

Arinius put his hand to his chest, needing to feel the familiar single loose leaf of papyrus beneath his tunic. He thought of his fellow brothers in Christ, each of them also smuggling a copy of a condemned text away from the community. They had parted company at Massilia, where it was said Mary Magdalene and Joseph of Arimathea had first come ashore to preach the word of God. From there Arinius and his brothers set sail for Smyrna in Asia Minor. From there, one was bound for the Holy City of Jerusalem and the plains of Sephal, another for Memphis, the last for Thebes in Upper Egypt. Arinius would never know if their efforts had been successful, any more than they would hear of him. Each was destined – burdened – to complete his mission alone.

Arinius considered himself an obedient and willing servant of God. He was not a particularly brave man, nor a lettered one, but he had found strength in his conviction that the holy writings should not be destroyed. He could not watch the words of Mary Magdalene and Thomas and Peter and Judas burning. Arinius still remembered the crack of the flames licking the air, red and white and gold, as the precious writings were consigned to the pyre. Papyrus and vellum, the quires and scrolls, the blister of Greek and Hebrew and Coptic turned to black ash. The smell of reed and water and glue and wax filling the stone courtyard of the community in the capital of Gaul that had been his home.

The papyrus shifted beneath his tunic, like a second skin. Arinius did not understand the text; he could not read the Coptic script, and besides, the letters were smudged, cracked. All he understood was that it was said the power contained within the seven verses of this, the shortest of the Codices, was absolute. As great as anything in the ancient writings of Exodus or Enoch, of Daniel or Ezekiel. More significant than all the knowledge contained within the walls of the great libraries of Alexandria and Pergamum.

Arinius had heard some of the lines spoken aloud by a fellow brother, and never forgotten them. An incantation, wonderful words sent free within the cool cloisters of the community in Lugdunum. It was an act that had precipitated the Abbot’s rage. Considering this Codex to be the most dangerous of all those proscribed books held in the library, he decreed it to be magic, a sorcery, and those who defended it were denounced as heretics. Enemies of the true faith. The novitiate was punished.

But Arinius believed he was carrying the sacred words of God. That his destiny, perhaps his entire purpose on God’s earth, was to ensure that the truth contained within the papyrus was not lost. Nothing else mattered.

Now, floating across the still waters to where he stood on the banks of the river Atax, the toll of a bell for lauds. A simple song calling him home. Arinius raised his eyes to the city on the hill and prayed he would find a welcome there. Then he grasped his staff in his right hand, stepped out on to the wooden bridge and walked towards Carcaso.

Chapter 1

CARCASSONNE

JULY 1942

Sandrine jolted awake. Bolt upright, her eyes wide open, her right hand stretched out as if she was trying to grasp something. For a moment she was neither asleep nor awake, as if some part of her had been left behind in the dream. Floating, looking down at herself from a great height, like the stone gargoyles that grimaced at passers-by from the cathédrale Saint-Michel.

A sensation of slipping out of time, falling from one dimension into another through white, endless space. Then running and running, escaping the figures hunting her down. Indistinct outlines of white and red and black, pale green, their faces hidden beneath hoods and shadow and flame. Always the sharp glint of metal where should have been skin. Sandrine couldn’t remember who the soldiers were or what they wanted, if indeed she’d ever known, and already the dream was fading. Only the sense of threat, of betrayal, remained. And those emotions, too, were slipping away.

Little by little, the room came back into focus. She was safe in her own bed in the house in the rue du Palais. As her eyes became accustomed to the dark, she could pick out the bureau of bleached mahogany against the wall between the two windows. To the right of her bed, the high-backed couch covered with washed-green Chinese silk and the bamboo plant stand. Opposite, beside the door, the low bookcase, its shelves filled to bursting.

Sandrine wrapped her bare arms around her knees, shivering in the chill of the early morning. She reached for her eiderdown, as if by touching something real she would feel less insubstantial, less transparent, but her fingers found only the cotton of her crumpled sheet. The eiderdown, kicked off in the night, lay on the floor beside the bed.

She couldn’t see the hands on the clock on the chest of drawers, but there was something in the quality of the light coming through the gaps in the shutters, the song of the blackbirds in the street outside, that told her it was nearly morning. She didn’t have to get up, but she knew she wouldn’t go back to sleep now.

Sandrine slipped out of bed and tiptoed across the room in her bare feet, trying to avoid the worst of the creaking floorboards. Her clothes were piled, raggle-taggle, over the arm of the cane-backed chair at the foot of her bed. She wriggled out of her nightdress and dropped it to the floor. Though she was eighteen, Sandrine still looked like the tomboy she had been, a garçon manqué. She was all arms and legs, there was nothing soft about her. Her black hair refused to be tamed and she had the deep complexion of a country girl, tanned from days spent out of doors. Powder made no difference. As she threaded her slim arms into the sleeves of her cotton blouse, she noticed a smudge on the inside of the wide round collar where she’d experimented yesterday with her sister’s face powder. She rubbed at it with her thumb, but it was stubborn and wouldn’t shift.

The skirt was too big, a hand-me-down. Their housekeeper, Marieta, had moved the hook and eye, taking in a good two inches at the waist, so even though it didn’t hang quite right, it was wearable. Sandrine liked the feel of the sateen lining against her legs, the way the chequered pattern shifted through squares of red and black and gold when she walked. In any case, everyone wore hand-me-downs these days. The sleeveless pullover was her own, a blowsy burgundy, knitted by Marieta last winter, that half argued with, half suited, her colouring.

Perching on the edge of the chair, Sandrine pulled on her écossaises, the precious tartan socks her father had brought back as a gift from Scotland. His last trip, as it turned out. François Vidal had been one of the many Carcassonnais who had gone to fight and never come home. After the months of waiting, seeing no action – the drôle de guerre, the phoney war as it had become known – he was killed on 18 May 1940 in the Ardennes, along with most of his unit. A muddle of orders, an ambush, ten men dead.

It had been two years. Although she still missed her father – and her nights were often broken by bad dreams – she and Marianne had learnt to carry on without him. The truth was, much as Sandrine hated to admit it, the outline of his face and his gentle smile were less clear in her mind with each passing month.

In the east, the sun was rising. Light filtered through the patterned glass of the arched window on the stairwell, casting a kaleidoscope of blue and pink and green diamonds on to the rust-red tiles. Sandrine hesitated a moment outside her sister’s bedroom. Even though it was her intention to sneak out, she had a sudden urge to check that Marianne was there, safe in her bed.

Sandrine put her hand on the ornate metal door handle and crept in. She tiptoed over to the bed. In the grey half-light, she could just make out her sister’s head on the pillow, her brown hair wrapped in complicated knots of paper and rollers. Marianne’s face was as beautiful as ever, but there was a spider’s web of worry lines around her eyes. Sandrine could just make out her shoes beside the bed. She frowned, wondering where she had been for them to be caked in mud.

‘Marianne?’ she whispered.

Her sister was five years older. She taught history at the École des Filles on Square Gambetta, but spent much of her free time at the centre run by the Red Cross in the rue de Verdun. Quiet and principled, Marianne had offered her services as a volunteer with the Croix-Rouge after France’s surrender in June 1940, when tens of thousands of dispossessed people from the Occupied Zone had fled south to the Languedoc. Then, her work had been to provide food, shelter, blankets for refugees fleeing the advancing Nazi forces. Now, it was monitoring the condition of prisoners being held in Carcassonne’s gaol or being sent to internment camps in the mountains.

‘Marianne,’ whispered Sandrine again. ‘I’m going out. I won’t be long.’

Her sister murmured and turned over in her bed, but did not wake.

Considering her duty done, Sandrine stole back out of the room and quietly closed the door. Marianne didn’t like her going out in the early morning. Even though there was no curfew in the zone non-occupée – the zone nono as it was known – there were regular patrols and the atmosphere was often jittery. But it was only in the stillness of the early morning, free from the restrictions and tensions and compromises of everyday life, that Sandrine felt herself. She didn’t intend to give up these moments of freedom unless she had to.

Until she had to.

Sandrine carried on down through the silently sleeping house, trailing her hand over the warm wood of the banister. Diamonds of coloured light danced at her heels. For an instant, she wondered if other girls, in other times, had felt the same as she did. Confined, caught between childhood and the adult life to come. And in the air around her, the echo of all those stifled hearts, trapped spirits, fluttered and sighed and breathed. So many different lives, passed over centuries in the narrow streets of the medieval Cité or in the Bastide Saint-Louis, whispered and cried out to be heard. Sandrine could not understand them, not yet, though a certain restlessness moved in her blood, her veins.

For the ancient spirit of the Midi, buried in the deep memory of the mountains and hills, in the lakes and the sky, had long ago begun to stir. To speak. The white bones of those sleeping in the cimetière Saint-Michel, in the cimetière Saint-Vincent and in the country graveyards of the Haute Vallée, were beginning to awake. A shifting, a murmuring through the cities of the dead, words carried on the wind.

War was coming to the South.

Chapter 2

A narrow corridor with high ceilings led directly from the foot of the stairs to the front door. Sandrine sat on the bottom step to lace up her shoes, then went to the hallstand. Two umbrellas were wedged into the base. Six brass hooks, three on each side of the mirror, held a selection of hats. Sandrine chose a plain maroon beret. Looking in the glass, she held her hair off her forehead and put the hat on, teasing out a few curls. Then she heard the rattle clatter of a pan and the bang of the screen door, and realised Marieta was already up and about. Little chance of getting out unobserved now.

Sandrine walked down the corridor to the back of the house. As little girls, she and Marianne had spent a good deal of time in the kitchen. Her sister loved to cook and was keen to learn. Sandrine was too impatient, did everything in a hurry. Perched up on the draining board beside the porcelain sink in Coustaussa to help strain the cherries for jam in summer when she was three or four. When she was six, being given the mixing bowl and wooden spoon to lick when Marieta baked cakes for the bataille des gabels to celebrate the fête de Saint-Nazaire in Carcassonne. At eight, sprinkling flour over the old wooden table while Marieta taught Marianne how to knead the dough for her pan de blat, the rustic wheat bread not available in the boulangeries in Couiza.

She paused on the threshold. Marieta grumbled that the kitchen was too small, but it was cool and well stocked and efficient. Metal pots and pans hung from hooks above the fireplace, where a modern gas cooker had been installed. A deep enamel sink with a large draining board, and a tall dresser so that the plates and cups were easily within reach. High windows filled the entire back wall. Even though it was early, all four were tilted wide open. Bundles of wild rosemary, dried tarragon and sprigs of thyme gathered at Cavayère hung from the wooden rack suspended from the ceiling.

‘Marieta,’ she said. ‘Coucou, c’est moi.’

Marieta was sitting at the table with her back to the door, breathing heavily. Beneath a wrapover housecoat, today’s a pattern of yellow and pink field flowers, she wore her customary black, cotton rather than wool her only concession to the season. Buttoned up to the neck and at the cuffs, with dark stockings and sabots, the heavy wooden clogs she always wore. Wisps of grey hair were escaping from the bun at the nape of her neck and her chest wheezed, her breath full of dust.

‘Coucou,’ Sandrine said again, putting her hand on the old woman’s shoulder.

Marieta jumped. ‘Madomaisèla!’

‘I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to startle you.’

‘What are you doing up at this time?’

‘Couldn’t sleep.’

Marieta looked her up and down, taking in the beret and outdoor shoes.

‘You know your sister doesn’t like you to go out on your own.’

‘I did tell her.’

Marieta raised her eyebrows. ‘But did she hear you?’

Sandrine flushed. ‘I didn’t want to wake her up.’

The housekeeper leaned forward and picked a stray piece of crimson wool from Sandrine’s skirt.

‘And if Madomaisèla Marianne asks where you are?’

‘She won’t, she was awfully late home last night.’ Sandrine paused. ‘Do you know where she went?’

Their eyes met. On the wall above the door, the hands of the clock moved round. One tick, two ticks, three.

Marieta was the thread that held the woven life of the household together. Originally from Rennes-les-Bains, she had spent her life in the service of others. Devout and loyal, she had been widowed young, in the Grande Guerre. She had come to help after Madame Vidal had died, unexpectedly, eighteen years before.

She claimed to be content to live in Carcassonne, though Sandrine knew she missed the ancient green forests of her childhood, the quiet village streets of Coustaussa and Rennes-les-Bains. When war had broken out in 1939, Marieta took it in her stride, saying she had survived one war and would survive another. After the telegram informing them of Monsieur Vidal’s death, there had been no more talk about her going home.

‘Do you?’ Sandrine said again.

Marieta pretended she hadn’t heard. ‘Well, if you are determined to go out, you’d better have something inside you.’

Sandrine sighed. She knew if Marieta didn’t want to talk about something, she wouldn’t.

‘I am hungry,’ she admitted.

Marieta lifted the linen cloth on the table, releasing a sweet smell of flour, rosemary and salt, to reveal a freshly baked loaf cooling on a wire tray.

‘White bread!’

Marieta cut a slice, then gestured to the blue china dish in the centre of the table.

‘And butter,’ she said. ‘Delivered this morning.’

Without thinking how it might embarrass the older woman, Sandrine threw her arms around her. The familiar scent of lavender water and sulphur lozenges was reassuring, taking her back to a place before the war, before her father’s death. To a simpler and easier time.

Marieta stiffened. ‘What’s the matter? Did you have another bad night?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘At least, I did, but it’s not that. It’s . . .’

‘Well then, sit. Eat,’ Marieta said, then spoke in a softer voice. ‘It will be all right, you hear? These times will pass. France will be France again. There are enough good men – men of principle, men of the Midi – they won’t sell us out. Not like those criminals in Vichy.’

Sandrine looked down at the piece of bread, her appetite suddenly gone.

‘But what if it stays like this for ever? Nothing getting better? Always the fear of things getting worse?’

‘We will bide our time,’ she said. ‘Keep our heads down. The Germans will stay north of the line, we stay south. It won’t last for ever. Now, finish your breakfast.’

Marieta watched until she’d finished every scrap. Then, before Sandrine could clear up after herself, she was on her feet and carrying the plate over to the sink. Sandrine brushed the crumbs from her skirt and stood up too. She wasn’t sure why she felt so out of sorts.

‘Is there anything you need in town, Marieta?’

‘Not that I can think of.’

‘Surely, there’s something? I want to do something.’

‘Well,’ said Marieta eventually, ‘I suppose if you are going that way, I promised this dress pattern to Monsieur Quintilla’s wife.’ She took an envelope from the drawer. ‘I meant to deliver it myself, but it is such a long walk down to the café at Païchérou and . . .’

‘It’s no trouble.’

‘Only if you’re going that way.’

‘I can.’

‘But don’t go over the bridge,’ Marieta warned. ‘Madomaisèla Marianne would say the same. Stay on this side of the river.’

Chapter 3

Sandrine ran down the steep steps to the small courtyard garden at the back of the house. She got her bicycle and pushed it out into the street. The gate rattled shut on its latch behind her.

She felt her mood lift as the air rushed into her lungs. Tilting her face to the morning, she dropped her shoulders and felt the cobwebs blow away. She picked up speed as she crossed the rue du Strasbourg, weaving in and out of the elegant platanes that lined the square behind the Palais de Justice, then left into the rue Mazagran.

The ebb and flow of life as it used to be was most evident in the elegant nineteenth-century beauty of this quartier, all grey stone and wrought-iron balustrades, the chalky pinks and blues of the decorative tiles and plaster on the front of the maisons de maître. On mornings such as this, when the lilac sky told of another hot day to come and the green underside of the leaves shimmered silver in the light breeze, it was impossible to believe that much of France was under German occupation.

The Bastide had come into being in the mid thirteenth century, some fifty years after the medieval crusade that had given Carcassonne its bloody notoriety. The vicious wars of religion had turned the inhabitants of the medieval Cité into refugees. Evicted in 1209, with only the clothes they stood up in, after the treacherous murder of their leader and ruler, Viscount Trencavel, it was only in 1276, some years after the last Cathar stronghold had fallen, that the French king gave permission for a new settlement to be established on the left bank of the Aude.

Despite the fact that Sandrine had lived her whole life in the Bastide, she loved the Cité more. And although she felt guilty even for thinking it, a part of her was grateful that, thanks to Maréchal Pétain’s collaboration with Berlin, she did not have to witness German soldiers walking through the cobbled streets of old Carcassonne.

The bells of Saint-Michel were ringing the half-hour as she crossed Square Gambetta, then cycled down the rue du Pont Vieux. Then, suddenly there it was – la Cité – on the hill on the far side of the river. The sight of it never failed to take her breath away.

For a moment, Sandrine was tempted to cross the bridge, but mindful of the promise she’d made to Marieta, she instead turned right. This first stretch of the bank, between the Pont Vieux and the weir above Païchérou, was the prettiest. Silver olive trees, fig trees in the gardens of the large houses. Ivy trailed down painted walls and ironwork trellises with vines. Elegant canopies and awnings and white terraces. Bougainvillea, carnations in pots, red and pink and white.

She pedalled along the water’s edge, twigs and stones spinning under her wheels, and arrived at the café. Before the war, tea dances were held at Païchérou each Sunday afternoon, the waiters in their white jackets, and long refectory tables laid out in rows. For a moment, grief caught in her throat, an old memory taking her by surprise. Her father had promised to take her for her twenty-first birthday, a promise he would no longer be able to keep.

The gates into the grounds were open. Sandrine propped her bike against the wall, then knocked at the door. She waited, but no one came. She knocked again.

‘Madame?’

She went to the window and peered in. It was dark inside. Everything looked closed up. Sandrine was in two minds as to whether to leave the envelope – Marieta was careful about her belongings. In the end, she posted it through the letter box and decided she’d come back later to make sure Madame Quintilla had got it.

Sandrine had intended to go straight home from Païchérou, but she’d heard rumours that refugees had set up a camp on the far side of the river. She was curious to know if it was true.

She cycled towards the weir and the secluded pocket of trees that stood at the bend of the river, just below the cimetière Saint-Michel. A glade of pine and beech, elm and ash. This morning, though, it felt a little too secluded. Sandrine found herself glancing over her shoulder, with a prickling on the back of her neck as if someone was watching her. The flapping of a collared dove, then the slither and splash of a fish in the shallows made her jump.

Sandrine stopped at the water’s edge and looked across to the far side of the Aude. She could see nothing unusual at all, nothing different or threatening or out of place. No tents, no gypsy encampment, no shadow city. She wasn’t sure if she was disappointed or relieved.

The sky was the colour of forget-me-nots. The bells of Saint-Gimer below the Cité began to ring seven o’clock, the sound floating across the mirrored surface of the water. Minutes later, they were answered by the bells of Saint-Michel and other churches of the Bastide. There had been a time, during the early days of the war, when the bells were silenced. Sandrine had missed them then, the familiar steady marking of each day. Now, though they rang again, she couldn’t help hearing a sadness in their voice.

She laid her bike down, then sat on the bank and pulled at the grass with her fingers. Before the war, at about this point in July, they’d be getting ready to leave Carcassonne for their summer house in Coustaussa. Her and Marianne, their father. Marieta fussing and packing three times as much as they needed. Picnics on the banks of the river Salz in the deep shade of the afternoon with her oldest friend, Geneviève. Cycling to Rennes-les-Bains for supper at the Hôtel de la Reine in the evening. Playing ‘Docteur Knock’ in the kitchen for hour upon hour with the battered old playing cards.

Sandrine leant back against the trunk of the tree and looked at the towers and turrets and spires of the medieval Cité, the walls of the Château Comtal and the distinctive thin outline of the Tour Pinte. Like a finger pointing to heaven. And, between the two Carcassonnes, lay the river. Still and flat and silver.

Like a sea of glass.

Codex II

GAUL

CARCASO

JULY AD 342

The shimmering waters of the river Atax glinted bright in the early morning sunlight. The young monk crossed the wooden bridge, then followed the track that led up to the main gates on the eastern side of the fortified town.

Ahead, Arinius could see the walls of Carcaso, not much more than twice his own height perhaps, but wide and solid. They looked strong enough to keep out any invaders. The foundations were large stone blocks, two or three deep, with a layer of mortar on the top. The façade was a mixture of lime and rubble. Spaced at regular intervals were horseshoe-shaped bastions, short squat towers on the northern section of the walls, curved on the outside and flat on the side facing the town.

‘A place of refuge,’ he said, praying that it would be the case. He was weary and intended to rest in Carcaso for a few days, to gather his strength for the final leg of his journey into the mountains. His throat was sore and his ribs ached from coughing.

Pressing his hand against the dry papyrus beneath his grey habit – an action that was now as natural and unconscious as breathing – Arinius joined the early crowd waiting to gain access to the town. Merchants, farmers from the faratjals, the pastures on the plains below the hill, weavers and those with pottery or ceramics to sell. Even in these uncertain times, this trade route along the coast of Gaul remained one of the busiest. Traders and wine sellers travelling to and from Hispania. Rumours of marauding bagaudes, bands of deserting soldiers or barbarians from the East, could not deter the men and women of commerce.

Arinius pulled his hood over his head as he approached the gate, a coin in his hand ready to pay the toll. An old denarius, though he felt sure it would still be accepted. Money bought nothing these days, but silver was silver. His heart began to thump. If the Abbot had put a price on his head, it was at the gates of Carcaso he was likely to be taken. Branded not only a heretic, but also a thief.

‘Protect me, Father,’ he murmured, making the sign of the cross.

The crowd shuffled forward once more. The wheels rattling on an old cart, struggling over the rough ground. A flock of geese, herded by a scrawny girl with arms like sticks, a dog snapping at the heels of its choleric owner. Another step forward. Just then, a mule kicked its back leg, sending a barrel flying. The wood split and red wine began to leak out, like a seam of blood on the dry earth.

Arinius pushed the image away.

The merchant started shouting and began to remonstrate with the owner of the animal, their words turning the pale morning air blue. Grateful for the diversion, Arinius slipped in front of them and up to the gate. There were two guards on duty. One, a brutish-looking man, was watching the altercation with a greedy glint in his eyes, itching for a fight. The other, a young man with a pockmarked face and a helmet too large for him, looked tired after his night’s watch.

‘Salve,’ said Arinius quietly. ‘Greetings, friend.’

‘Where are you from?’

‘Massilia,’ Arinius lied, holding out the silver coin. It was significantly more than required and the boy’s eyes widened. He took it, tested it between his teeth, then waved Arinius through.

‘Salve,’ he said with a grin. ‘Welcome to Carcaso.’

Chapter 4

CARCASSONNE

JULY 1942

Sandrine was woken by a squeal of tyres on the road as a motorbike took the corner too fast. She blinked up through the quilt of dappled leaves, for a moment not sure where she was. Trapped once more in the same nightmare? Then, the sound of the bells of Saint-Gimer striking the half-hour, and she remembered.

She sat up, picking a twig out of her hair, and looked out across the river. The sun had climbed higher in the cloudless sky. Way upstream, she heard the plash of the water against Monsieur Justo’s barge as he pulled hand over hand on the wire. If the ferry was working, it must be past nine o’clock.

Sandrine scrambled to her feet. As she grabbed her beret, something caught her eye ahead of her in the reeds. Something blue, beneath the overhang of the marsh willow. She paused, certain it hadn’t been there before. She walked upstream, along the water’s edge, moving out of the bright sunlight into the green shadow beneath the tree.

She bent down. It was a man’s jacket, snagged half in and half out of the water. Sandrine reached out to get it, but it was caught on the underside of a branch and it took a couple of pulls to get it free. Holding the dripping material away from her, she examined it. The pockets were empty, apart from a heavy silver chain, the sort of thing a man might wear. The catch was broken and initials – ad – had been carved on the underside.

She frowned. It wasn’t unusual for things to be jettisoned in the river, old boxes, flotsam, torn sacks from the market gardens upstream. But not clothes, not jewellery. Everything had a price or could be traded for something else. And the Aude was fast at this point; there were no rocks on this side of the river, only reeds and grass and flat riverbank that curved gently, so mostly the current sent its cargo rushing downstream.

Sandrine looked out over the river. Now she noticed there was something else in the water, caught on the ridge of jagged rocks below the weir. Pushing the chain into her pocket, she shielded her gaze with her hand, reluctant to believe the evidence of her own eyes.

It looked like someone trying to swim. One arm stretched out, the white material of the shirt billowing in the current, the other holding on to the rocks.

‘Monsieur?’ she shouted, hearing the fear in her voice. ‘Monsieur, do you need help?’

Her voice sounded thin, not loud enough to carry above the roar of the water over the weir.

‘Monsieur!’

Sandrine looked around for help, but the ferry had reached the far bank and was out of earshot. She dropped the jacket on to the grass and ran up towards the road. There was no one about, no sign of the motorbike she’d heard, no one walking past.

‘Help, I need help,’ she shouted.

There was no answer, no movement, just shadows reflected in the water, a pattern of light and dark. Sandrine ran back to the river, hoping she’d imagined it, but the man was still there, on the rocks beneath the weir, his shirt moving to and fro in the current. It was down to her. There was no choice. There was nobody else.

She removed her shoes and her socks, tucked her skirt into her underwear, then waded out into the water.

‘I’m coming, hold on.’

The further she went into the current, the faster the water swirled about her legs, harder and fiercer against her calves, her knees, the backs of her thighs. Deeper, colder. Sandrine struggled not to be knocked off her feet.

‘Hold on,’ she cried again.

Finally, she was close enough to touch him. A young man, unconscious, dark skin, black brows, long hair. His head lolled to one side. His mouth and nose were out of the water, but his eyes were closed. She wasn’t sure if he was breathing or not.

‘Monsieur, can you hear me?’ she said. ‘Take my hand, if you can.’

He didn’t respond.

Steeling herself, Sandrine reached out and touched him. Still nothing. She took a deep breath, then manoeuvred herself around so that she could get her hands beneath his armpits. She tried to pull. At first, nothing happened, he was held somehow on the rocks. But then his grip slackened and after a few more heaves, suddenly he came free.

Sandrine lurched and nearly collapsed under the sudden responsibility of his weight, but then the water took over and held him up. Feeling the squelch of mud between her toes, slowly she began to drag him back to the bank. She tried not to look at his pallid skin and lifeless features, his dark hair. She thought he was breathing, hoped he was. Tiny sounds seemed to be coming from his mouth, but she wasn’t sure. Every drop of her strength was focused on the task of getting him back to the safety of the shore.

As the water became shallower, he grew heavier in her arms. The last few steps were almost impossible, half dragging, half pulling, until his upper body at least was out of the water. With what little energy she had left, she managed to roll him on to his side before sinking to the ground on the grass beside him.

She took deep breaths, steadied her heart. A few moments later and she forced herself to look at him properly, at his bruised and lifeless face. There were rope burns around his wrists, red marks on his lower arms. Not the sort of marks he could have got from the water. She looked at his feet, seeing the soles were also bruised.

Sandrine swallowed hard. Not drowned. Rather, someone had tied him up, beaten him. She took another deep breath, fighting the panic that was threatening to overwhelm her, trying to work out what might have happened.

Without warning, the man’s eyes snapped open. He coughed, started to choke, as if the oxygen had suddenly started to feed into his lungs again. Sandrine leapt back, just as a stream of river water spewed from his mouth. He attempted to sit up, but he had no strength and fell back to the ground.

‘Spirits of the air,’ he muttered. ‘The number was ten thousand times ten thousand . . .’

His eyes were staring at her. Pleading, suffering eyes, shot through with despair.

‘Don’t move,’ she said quickly, trying to sound calm. ‘I’ll get help. You need help.’

‘Tell Baillard,’ he whispered. ‘Trouvez-lui. Dîtes que . . .’

‘I’ll fetch help,’ she said. ‘The police, we—’

His hand shot out and grabbed her wrist. Sandrine stifled a scream.

‘No police. Can’t trust . . . no!’ he gasped. ‘Tell the old man, tell . . .’

‘A doctor, then,’ she said, trying to prise his fingers from her skin. ‘You need help, I must fetch someone. You can’t—’

‘Tell him . . . it’s true. A sea of glass, of fire. Speak and they will come.’

‘I don’t understand,’ she said desperately. ‘I don’t know what you mean.’

‘The spirits of the air . . .’ he whispered, but his voice was fading.

‘No, don’t give up . . .’

A terrible rattling in his throat. A gurgling, then a snatching at the air. Every gasp of breath hard fought for.

‘Save your strength. Help is on its way,’ she lied, glancing up to the road again.

‘All true,’ he repeated, almost looking as if he was smiling. ‘Dame Carcas . . .’

‘It will be all right. Just . . .’

But he was drifting away, his colour fading from pink to grey to white. Sandrine kept shaking him, trying to keep him with her. Her wet skirt was clinging to the back of her legs as she pushed against his chest, her feet muddied and cut from the stones on the riverbank.

‘Hold on,’ she said, trying to keep him breathing. ‘Help will come soon, hold on.’

Then she felt a prickling on the back of her neck. Someone was there. Someone was standing behind her.

‘Thank God,’ she started to say, except something felt wrong.

Fear, rather than relief, jabbed her between the ribs. She spun round, but she was too slow. A blinding pain at the side of her head, dazzling white and yellow and red light, then she was falling, falling, her legs buckling under her. The smell of the river and the reeds, rushing up to meet her. A hand on the back of her neck, pushing her face down into the water. The river, framing her face now, lapping into her mouth, her nose, the shimmer of shadow and light on the surface.

For an instant, a whispering. A voice she couldn’t identify, a sound heard but not heard. Experienced somewhere beyond language, beyond hearing.

‘Coratge.’ A girl’s voice, glistening in the light. Courage.

Then, nothing.

Chapter 5

THE HAUTE VALLÉE

Audric Baillard stood in a clearing at the edge of a beech wood in the French Pyrenees. Rather than his customary pale suit and panama hat, he was wearing the nondescript clothes of a man of the mountains. Corduroy trousers, an open-necked shirt with a yellow handkerchief at his neck, a wide-brimmed hat. His skin was tanned, the colour of leather, and heavily lined. He was old, but he was strong, and there was a resolve in his eyes that bore witness to the evidence of his years.

Beside him, mopping his brow in the heat, was a smartly dressed man in a black suit and iron-grey trilby, with a fawn trench coat over one arm and a leather valise. At his side, two silent little girls and a thin woman with dead eyes. A little apart stood a young man in country smock and boots. All around, the sounds of the forest. Rabbits, squirrels, wood pigeons calling one to the other.

‘Good luck,’ said Baillard.

‘I can’t thank you enough,’ the American, Shapiro, replied, pulling an envelope from his pocket. ‘I hope this is sufficient . . .’

Baillard shook his head. ‘It is not for me, my friend. It is for your guides, the passeurs. It is they who take the risk.’

‘Didn’t mean to offend you, sir.’

‘I am not in the least offended.’

The American hesitated, then put the envelope back in his pocket. ‘If you’re sure?’

‘I am.’

Shapiro glanced at his guide, then lowered his voice so the woman and children couldn’t hear.

‘But as a businessman, sir, I hope you don’t mind me asking what’s in it for you?’

‘Merely to be of assistance,’ Baillard said quietly.

‘Though you’re taking a chance too?’

Baillard fixed him with his steady, quiet gaze. ‘These are difficult times.’

Shapiro’s face clouded over. Baillard knew that this man’s family, French Jews, had been among the first to be rounded up in Paris. He had come over from America, thinking his money might save them, but in twelve months he had succeeded only in finding his brother’s wife and two of her four children. The others had disappeared.

‘You cannot blame yourself,’ Baillard said softly. ‘Because of you, Madame Shapiro and your nieces have a chance. We each do what we can.’

Shapiro fixed him with a look, then he nodded. Something in Baillard’s voice persuading him of his sincerity.

‘If you’re sure,’ he said again. He glanced once more at the passeur. ‘What about this guy, does he speak English?’

‘No. Very little French either.’

Shapiro raised his eyebrows. ‘So what am I looking out for? The landmarks, in case we get split up.’

Baillard smiled. ‘I am sure you will not, but in any case, the route is simple. Keeping the sun ahead of you, you follow the draille, these wide tracks the shepherds and goatherds use. You’ll cross several brooks, passing through open meadows as well as sections of woodland. The first lake you come to will be the Étang de Baxouillade. Keep the water on your left. You’ll travel through a pine forest and on further, until you reach the banks of the Étang du Laurenti. There, all being well, a second passeur will be waiting. He will be accompanied by three others who are making the crossing today. He will take you over the summit of Roc Blanc, ready for the descent to the border with Andorra.’

‘This guy’s not sticking with me?’

‘There are different guides for different sections of the mountain. I cannot say for certain, but I think it likely your second aide will be a Spaniard.’

‘That’s grand. I have a little Spanish.’

Baillard smiled. ‘At the risk of now offending you, monsieur, I would recommend you keep conversation to a minimum. Your accent will give you away.’

‘You could be right,’ he said amiably, acknowledging the comment with good grace. ‘How long do you figure the journey will take, sir? Give or take?’

‘With the children, perhaps four hours to the Étang du Laurenti, then another two hours to the summit of Roc Blanc. The descent will be easier.’

The passeur cleared his throat. ‘Sénher, es ora.’

Shapiro turned round, then back to Baillard. ‘What’s that he’s saying?’

‘That it is time to leave.’ Baillard held out his hand. ‘The passeurs know these paths, this mountain. They know where the risk of being spotted by a patrol is at its highest. Do as they tell you.’

‘Here’s hoping,’ said Shapiro, clasping Baillard’s hand and shaking it. ‘And if you’re ever in New York, you look me up. I mean it.’

Baillard smiled at the American’s confidence, hoping it was not misplaced. In the two years he had been helping smuggle people over the Pyrenees – exiles, fugitives, Jews, communists, those without an exit visa – many had ended up imprisoned in gaols in Spain or repatriated to France. Americans in particular did not understand that, in this war, money did not talk.

‘Pas a pas,’ he murmured to himself.

He watched the small party set off along the path. Like so many of the wealthy refugees Baillard had guided to the escape routes, they had brought too much with them. The American was not dressed for the mountains, the children would struggle with their cases and the woman looked defeated, someone who had seen too much to think she could ever be safe again.

Baillard sighed, wished them luck, then turned and retraced his steps to the village of Ax-les-Thermes. The air was fresh and clean, but the sun was hot and would get hotter, and he was tired. He had walked many thousands of miles through these mountains, and he accepted that the time was coming when he would no longer have the strength required for such arduous journeys.

He knew many of the secrets hidden in these hills, yet an explanation for the purpose of it all eluded him. He had published books – on folklore, on the bloody history of the region, about the citadel of Montségur and the caves of the Sabarthès and Lombrives and the mountain peaks of the Vicdessos – but still the truth of his continuing mission remained stubbornly beyond his comprehension.

He took one last look. His charges were specks on the horizon, five diminishing figures walking slowly uphill. He said a prayer for them, then turned and slowly began his descent.

It took Baillard nearly an hour to reach the outskirts of the town. There, he changed back into his usual clothes. He noticed a police car idling at the corner of the road and quietly changed direction. The police did not notice him. Or if they did, they had no interest in an elderly man in a white suit taking the morning air. But he took no chances, no unnecessary risks. It was why he had never been caught, not in this conflict nor in any other war in which he had been called upon to play his part.

He circled the town, walking slowly, with apparent lack of purpose, then came back in through the northern streets and went to the Café des Halles by the bridge, where he was to wait. The local doctor was due to visit a pregnant woman, expecting twins any day now, and had agreed to take him back to Rennes-les-Bains, where he hoped the package from Antoine Déjean would be waiting. Baillard allowed himself a moment of anticipation. If all was well, then there was a chance.

‘Come forth the armies of the air,’ he murmured.

Old words, ancient words, from a sacred text Baillard believed destroyed more than fifteen hundred years ago.

But what if the rumours were true? If it had survived?

He glanced at his watch. At least three hours to wait, if the doctor came at all. He ordered something to drink and eat. The café only had thin wine and ersatz coffee. No milk, of course. But Baillard didn’t require much. He ate a dry biscuit, dipping it into the tepid brown liquid, and sipped the rough mountain rosé.

He had seen many summers such as this, the gold of the sunflowers and the pinks, blues and reds of the mountain flowers fading into wine-coloured autumns as the leaves fell. Harsh winters following on behind, the passage of rain and mist to snow and ice. The endless march of the seasons. So many years, wondering whether each might be his last.

The sun rose higher in the sky. Baillard continued to wait and to watch the road, looking for anything, anyone out of place. There were spies everywhere, undercover rather than in plain view as in the occupied zone, but here all the same. Members of the Kundt Commission, the branch of the Gestapo operating in the zone non-occupée; SD and SS of course, but also Deuxième Bureau. Willing partners with the invaders whose aim in time, he had no doubt, was to subjugate all of France.

Baillard took another sip of wine. The uniforms were different in each age, the battle colours under which they marched changing as the centuries marched on. Boots and guns had replaced banners and horses, but the story was the same.

Men with black hearts. With black souls.

Chapter 6

CARCASSONNE

‘A sea of glass . . .’ she murmured, bright in the shimmering.

Sandrine knew it was her own voice she was hearing inside her head, but it seemed to be coming from a long way away. Shapes shifting, fragments of sound. An echo slipping in and out of conscious thought, as if underwater. Or through the clouded gaps between the valleys. She felt the hard metal of the chain in her pocket digging into her hip. She pulled it out, but her fingers didn’t seem to work and the necklace slithered to the ground.

‘Mademoiselle, can you hear me?’

Now she was aware of her hair being stroked gently off her forehead.

‘Mademoiselle?’

A man’s voice, sweet, soft, and a scent of sandalwood. So close, she could feel his breath on her skin.

‘It’s all right,’ he said. ‘It’s all right, you’re safe now.’

‘Sleep,’ she murmured.

‘You shouldn’t sleep,’ he said. ‘You must wake up.’

Sandrine felt his hands beneath her shoulders, then the warmth of his skin through his shirt as he held her against him. ‘Open your eyes,’ he was saying. ‘Try to wake up. Open your eyes.’

She felt herself growing heavy in his arms, slipping away again. Then, his lips on hers, the lightest of touches. Breathing life into her. A kiss. Sandrine felt something inside her stir, a shock, a jolt. Then he kissed her again. For a single, unique moment, her eyes fluttered open, but she couldn’t seem to see.

‘I . . .’ she murmured, as her eyes closed once more. ‘I can’t . . .’

Now his hand was cupping the back of her neck, cradling her head in his arms.

‘Wake up. Please, mademoiselle. Sit up.’

Sandrine was aware of the sound of an engine, a different timbre from the motorcycle she’d heard earlier. Louder, a car coming closer. She felt the man’s muscles tense, then she realised she was not in his arms any more. She was being laid back down on the grass, his skin no longer touching hers.

‘You’ll be all right,’ he said.

Sandrine wanted him to stay. Wanted to ask him to stay, but the words wouldn’t come. The car was getting closer, the belch of an exhaust.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said, his voice fading. ‘I’m sorry, I can’t be found here . . . I’m sorry.’

Then he was gone. The air was still, empty. She could feel herself drifting away again. The smell of the riverside giving way to other scents, wild lavender and rosemary, the green and purple of the valleys around Coustaussa. Honeysuckle and the sharp tang of wood smoke in winter. Images now, cold reflections. The old wooden sign on the back road marking the way to the castillous, the arms crooked like a broken cross. In town, walking alongside her sister and her father beneath a red and yellow CGT trade union poster, a demonstration, before the war. Everyone singing for peace, for liberty, as they walked past the gardens and white balustrades and the marble angel statue in the centre of the lake in Square Gambetta.

‘Paix,’ Sandrine murmured.

Carcassonne had marched for peace in 1939, but war had come all the same. In 1940, defeat had come all the same. Their voices had counted for nothing.

‘Patz,’ she murmured again. ‘Peace.’

Codex III

GAUL

CARCASO

JULY AD 342

The young monk made his way through the crowds of people filling the narrow streets of the fortified town. Despite the air of trade and commerce, and the brave attempts of everyone to behave as if nothing had changed, Arinius detected a hint of unease, of watchfulness in the air. The same atmosphere that was spreading through all of Gaul since the death of Emperor Constantine. All around him, hands hovering ready to draw a knife from its hilt, eyes darting this way and that.

Arinius knew little of military strategy or the diplomacy of emperors and generals, but from stories overheard in the forum in Lugdunum or told by the merchants he’d met on the Via Domitia, he knew that the history of his country was one of invasion and counter-invasion. From century unto century, the imposition of a new set of values upon the old – defeat, then collaboration, then assimilation. The prehistoric tribes who once lived on the Carsac plains, the Celtic settlers who had come after them, the Volcae Tectosage three centuries before the birth of Christ, the armies of Augustus. Now, it was said, tribes were coming from the East to reclaim what Caesar once had ruled.

Arinius didn’t know how well or how often Carcaso had been called upon to defend her walls, but he could see they had been built to withstand siege and invading armies. The horseshoe-shaped watch towers in the northern sections were faced with courses of dressed ashlar and intersected by red brick. On the first floor of each tower, three semicircular windows were underscored by red-brick arches. The wooden walkway and the battlements, accessed by ladders set against the base of the walls, were guarded by foot soldiers in chain mail and silver helmets, some armed with a pilum, a weapon like a javelin, others carrying slings. Some were Roman, but many were clearly from local villages – typical of the limitanei, the frontier garrison troops who now protected even these outposts. Arinius wondered for whom these disaffected men on the walls would fight. For the failing Empire? For their neighbours and families? For God? He wondered if even they themselves knew where their loyalties lay.

There were four major streets, forming the shape of a cross within the walls, with other smaller roads connecting different quadrants of the town. Most of the buildings were tiled rather than the bush and thatch still common in the villages of the south. A small central square, a covered forum, was packed with merchants selling spices and herbs, geese and rabbits in wooden cages, wine, woollen tunics and strips of leather to patch broken sandals and belt fastenings. There was hammering from the forge, where a blacksmith worked on a scrawny bay mare.

Arinius saw many different skin colours and different ways of dressing. Some men wore beards, others had bare faces. Higher-born women with braided hair, jewelled and adorned, the daughters and wives of the Roman garrison commanders and men. Others walked freely with their heads uncovered in the older style, pale woollen tunics worn beneath hooded cloaks. It was hard to say who were natives, the original inhabitants of the land, and who the outsiders.

A fit of coughing caught Arinius by surprise. He doubled over, pressing his hand against his chest until the attack had passed, struggling to get his breath. He looked at his palm, saw spots of blood, and a wave of panic washed through him. He had to keep the illness at bay until the Codex was safe. That was all that mattered. Not his life, only that he fulfilled his mission.

He walked slowly on. He needed to rest. Arinius found a tavern opposite the residence of the garrison commander, an imposing two-storey house with red guttered tegulae forming the roof. Outside, the paved street was littered with clay pots, some broken, meat bones, and figs split and oozing rotting purple flesh, but inside the tavern was clean and it offered board and lodging at a reasonable price.

The formalities observed, Arinius drank two cups of wine, ate a handful of almonds and some hard white goat’s cheese with honey. Afterwards he lay down on the hard wooden bed. He unpinned his mother’s brooch, took off his cloak and used it as a blanket. Then, using his leather bag as a pillow, he folded his hands across his chest and, pressing the Codex close against his skin, Arinius slept.

Chapter 7

CARCASSONNE

JULY 1942

‘She’s coming round.’

A different voice this time. Another man, formal, educated, northern, not a local accent. Not the boy who had whispered to her, not the boy who had kissed her. The memory faded away. The real world returned, cold and hard and colourless.

‘Mademoiselle,’ the Parisian said. ‘Do you know what happened to you? Can you tell us your name?’

Sandrine was aware of the sharp grass, that she was cold and damp. She tried to sit up, but pain exploded at the base of her skull. She attempted to lift her arm, but she had no strength. The muscles and bones could not be made to work.

Then a woman’s voice, sing-song high. ‘Actually, I think I know who she is.’