July 2005. In the Pyrenees mountains near Carcassonne, Alice, a volunteer at an archaeological dig, stumbles into a cave and makes a startling discovery-two crumbling skeletons, strange writings on the walls, and the pattern of a labyrinth.Eight hundred years earlier, on the eve of a brutal crusade that will rip apart southern France, a young woman named Alais is given a ring and a mysterious book for safekeeping by her father. The book, he says, contains the secret of the true Grail, and the ring, inscribed with a labyrinth, will identify a guardian of the Grail. Now, as crusading armies gather outside the city walls of Carcassonne, it will take a tremendous sacrifice to keep the secret of the labyrinth safe.

Contents

THE RETURN TO THE MOUNTAINS

CHAPTER 63

Sabarthès Mountains

CHAPTER 64

CHAPTER 65

CHAPTER 66

CHAPTER 67

CHAPTER 68

CHAPTER 69

CHAPTER 70

CHAPTER 71

Montségur

CHAPTER 72

CHAPTER 73

Sabarthès Mountains

CHAPTER 74

CHAPTER 75

Montségur

CHAPTER 76

CHAPTER 77

Pic de Soularac

CHAPTER 78

Los Seres

CHAPTER 79

CHAPTER 80

Ariège

CHAPTER 81

Pic de Soularac

CHAPTER 82

Pic de Soularac

In the land of Egypt,

The master of secrets,

Gave words and scripts.

EPILOGUE

Los Seres

Braves amics, pica mièja-nuèit

Cal finir velhada

E jos la flassada

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SELECTED GLOSSARY OF OCCITAN WORDS

ambans wooden galleries built for defence around

battlements

ben good

benvenguda welcome

bonjorn hello

cadefalcs brattices

calèche an open carriage

calèlh oil lamp

coratge courage

défora outside

deman tomorrow

dintrar enter

doçament softly

faitilhièr a witch

faratjals pastures

filba daughter

gata a cat (type of siege engine)

graal grail

janvièr January

julhet July

libres books

Lo Ciutat the Cite

Lo Miègjorn the Midi

març March

menina grandmother

meravelhós miraculous

mercé thank you

molin blatier a wheat mill

montanhas mountains

Na Madame/Mrs

nenon baby

noblessa nobility

oc yes

oustâou home

paire father

pan de blat wheat bread

panièr basket

Payre Sant Holy Father

payrola cauldron

pec idiot

perfin at last

perilhòs danger

res nothing

Sénher Sir/Mr

sirjan d’arms sergeant at arms

sòrre sister

trouvère troubadour

vuèg empty

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Reading Group Notes

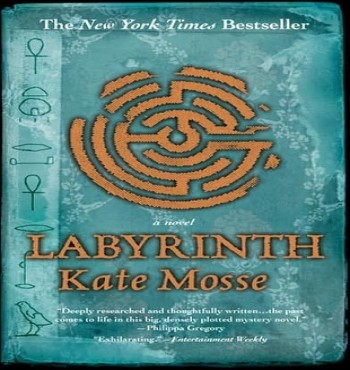

LABYRINTH

In Brief:

It’s July 2005. Dr Alice Tanner is a volunteer on an archaeological dig in the Pyrenees when she is unwisely drawn away from the rest of her group by an overwhelming sense of déjà vu. Dangerously dislodging a boulder that she later learns has concealed a cave for eight centuries, Alice stumbles upon two intact skeletons and a carving of a labyrinth that looks oddly familiar to her. The discovery is to provoke the intense interest of the local police, whom Alice immediately distrusts; but too late she realises that her actions have irrevocably placed many lives in danger – including her own. Alice has no choice but to rediscover her distant past, and act on what she learns before her present enemies catch up with her.

In Detail:

Labyrinth features two intelligently headstrong heroines, 17-year-old Alaïs Pelletier from 13th century Carcassonne and modern-day PhD graduate Dr Alice Tanner. It is a grippingly told adventure that skilfully blends the lives of these two women, separated by time but united in a common destiny. Both protagonists display tremendous reserves of courage, steadfastness and loyalty on their respective quests. They also, in the author’s own words, ‘have lovely frocks, sex and swords and don’t hang about waiting to be rescued’!

This is a stunning novel set in both medieval and contemporary southwest France. As the parallel storylines unfold, both ancient and modern-day conspiracies are unearthed, all revolving around three hidden books – The Book of Words, The Book of Potions and The Book of Numbers. Together, these tomes hold the secret of the true Grail, which dates back to the Ancient Egyptian era many years before Christ. The appointed Guardians of the Books, of which Alaïs’s father is one, must devote their lives to the protection of this secret. Meanwhile, back in the present day, Alice faces a race against time to put together the curiously familiar pieces of a jigsaw puzzle representing her long-buried history.

Set against a historical backdrop of religious persecution, Labyrinth also tells the story of a real-life Christian sect, the Cathars, who were a powerful presence in the community of Carcassonne from the late 11th century until the early 13th century. (The failure of military force to eradicate the Cathars led directly to the foundation of the Inquisition.) Seen as a rival to the Catholic Church, Catharism was a tolerant faith offering universal redemption, irrespective of the individual’s creed. It is this compassionate ideology that Alaïs and those closest to her must battle to protect. But in her efforts to also save the Books, Alaïs soon discovers she can trust no one – least of all her cruelly manipulative sister, Oriane.

Labyrinth’s story and colourful cast of characters resonate back and forth between past and present, but what remains constant throughout is a gripping plot and the depth and accuracy of the author’s research into the history and cultural landscape of the region. The language of the Cathars, particularly, is portrayed with richness and authenticity; as well as French snippets (the dialect of their persecutors) there is a fascinating and significant peppering of medieval Occitan words and phrases, with a glossary at the back for the reader’s reference.

Tightly plotted and packed with suspense, Labyrinth sets a new benchmark for adventure writing and gives precursors such as The Da Vinci Code more than a run for their money.

About the author:

Born in 1961, Kate Mosse was educated at Chichester High School for Girls and read English at New College, Oxford. On graduating, she started as a secretary at Hodder and Stoughton and went on to become an editorial director of Hutchinson, Random House. Kate is both the author of four previous books and a broadcaster – she presented BBC Four’s flagship Readers and Writers Roadshow, is the book reviewer for BBC Two’s The Culture Show, and is a guest presenter of Radio 4’s Saturday Review Open Book. The co-founder and Honorary Director of the Orange Prize for Fiction, Kate is additionally a trustee of Arts & Business, and was the first ever female Executive Director of the Chichester Festival Theatre.

In 2000, Kate Mosse was named European Woman of Achievement for her contribution to the arts. Together with her husband Greg Mosse, Kate runs courses for writers as well as the writers’ internet resource www.mosselabyrinth.co.uk. They have two children and divide their time between West Sussex and Carcassonne, southwest France.

Themed questions for discussion:

HISTORY

1. ‘History is a novel that has been lived; a novel is history that could have been.’ Discuss this quotation from E & J de Goncourt with reference to Labyrinth.

2. In the novel’s prologue, there are glimpses of the two time periods. Do you think it is important that, after the prologue, the author starts the novel proper with ten chapters set in the medieval past? How well do you think the twin storylines worked throughout the whole of Labyrinth?

INHERITANCE

3. ‘Last night’s ceremony had been exhilarating . . . she had felt transformed, fulfilled by the ritual and seduced by the power inherited from her grandfather’ (page 205). Consider Marie-Cïcile’s words and discuss the nature of inheritance with reference to other characters in Labyrinth. Can good or evil be inherited or must it be nurtured?

CHARACTERISATION

4. How quickly did you discover that some of the modern characters mirror or echo characters from the past? Which ones did you spot first? What were the clues?

5. ‘Guilhem shook his head. “Can’t you see what she’s doing, Alaïs? She’s trying to turn you against me”’ (page 503). Do you see Guilhem as an unhappy character, who never fully atones for his betrayal of Alaïs, or does he finally put things right?

6. Some of Labyrinth’s medieval characters are real. People with those names lived and breathed in the circumstances narrated 800 years ago. Did you notice anything different about the ‘real’ characters? (For example, Raymond-Roger Trencavel, Agnès de Montpellier, the papal legate and others.)

SETTING

7. Have you ever experienced, like Alice, such an affinity with a place that you seem to know who must have previously lived there and the emotions they enjoyed or endured? How did the novel’s setting(s) contribute to your enjoyment as a reader?

VIOLENCE AND ADVENTURE

8. ‘He raised his arm a second time and plunged his sword into the top of the old man’s skull, splattering red pulp and grey brains into the straw’ (page 196). There are very few scenes of violence in the novel, but those few are very graphic. Do you think they were ‘too much’, ‘not enough’ or ‘just right’?

9. In interviews, Kate Mosse has said that she wanted to tell an adventure story in which active women shaped their own destinies. One journalist called her ‘Wilma Smith’! Is this aspect of the adventure important to your enjoyment of the novel?

RELIGION

10. The 13th century Cathars were surprised by the extent of persecution against them. Although the Labyrinth story and the trilogy of special books have a spiritual element, they exist alongside Catharism, Christianity, Judaism and Islam, not as part of any of these faiths. How do you think the novel handles questions of religion? Can you draw any parallels with more recent religious conflicts?

To find out more about the characters and places in Labyrinth, visit www.mosselabyrinth.co.uk.

Suggested Further Reading:

Massacre at Montségur by Zoë Oldenburg

The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown

The Yellow Cross: The Story of the Last Cathars 1290–1329 by René Weis

The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho

The Last Templar by Raymond Khoury

The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón

The Boudica series by Manda Scott

Les Femmes Cathares by Anne Brenon

Eleanor of Aquitaine by Alison Weir

Audiobooks:

Read by Emilia Fox and Anton Lesser, the Labyrinth audiobook is available on CD at £16.99.

The

Laybrinth Walk

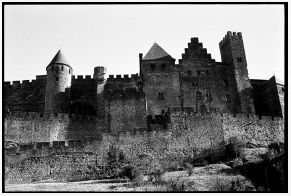

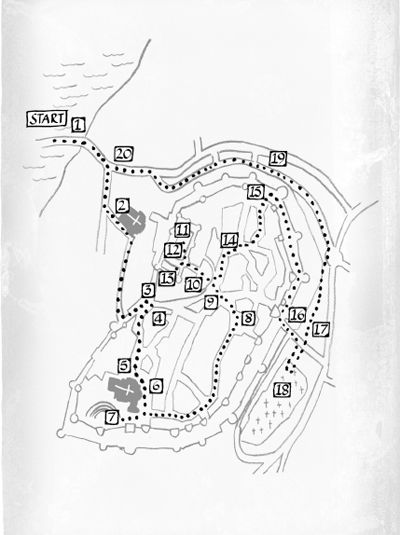

One of the reasons I wrote Labyrinth was because I was inspired by the amazing fortified medieval Cité of Carcassonne. I have written this guided tour – The Labyrinth Walk – so that you can see for yourself some of the sights that greeted my heroine, Alice Tanner, when she first stepped within the battlements. And, of course, the places that Alaïs Pelletier called home.

I think the tour should take about two hours. If you are tired, there is a short cut about two thirds of the way round. Of course, if you stop for lunch in the middle, who knows if you will ever finish it!

Carcassonne, January 2006

Author Biography

BY KATE MOSSE

Novels

Eskimo Kissing

Crucifix Lane

Labyrinth

Sepulchre

The Winter Ghosts

Citadel

Non-Fiction

Becoming a Mother

The House: Behind the Scenes at the

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

Plays

Syrinx

Endpapers

Historical Note

Note on Language

1

‘The Cité was set on top of a grassy hill. The slopes swept down to streets filled with red-roofed houses. On the flat land at the bottom there were fields of vines, fig and olive trees, wigwams of heavy ripe tomatoes in rows.’

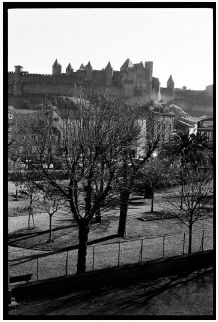

The best view of the fortified medieval Cité is from the Pont Vieux, the old bridge that links the Bastide Saint-Louis on the north bank of the River Aude with the citadel on the south. The Pont Vieux is closed to traffic so take it on foot. At night, the Cité is floodlit and looks like a movie set. The outer ring of walls was built in the middle of the 13th century, as additional fortifications, and was not there in Alaïs’ day.

On Tuesday 5 July 2005, the elusive Audric Baillard walks this way in Chapter 23 en route to Jeanne Giraud’s house.

2

‘The Pont Vieux led straight into the Quartier de la Trivalle, which had been transformed from a drab suburb into the gateway to the medieval Cité. Black wrought-iron railings had been set at intervals along the pavements to stop cars from parking. Fiery orange, purple and crimson pansies trailed out of their containers like hair tumbling down a young girl’s back.’

At the end of the Pont Vieux, turn sharp right into rue Barbacane – which follows the ancient path of the River Aude – past the Pharmacie. You will pass rue de la Gaffe on your left, before you arrive in Place Saint-Gimer.

To the left of the church – which was built in 1854 by Viollet-le-Duc, the man responsible for the restoration of the medieval Cité – are the ruins of a stone barbacane that replaced the two wooden palisades between which Alaïs threads her way to the hidden glade by the river in Chapter 2 to gather herbs.

3

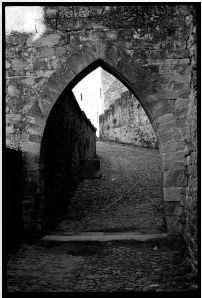

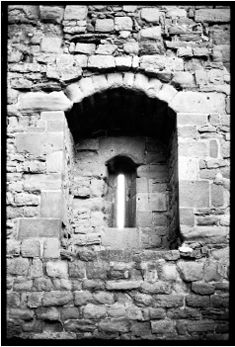

‘The path down to the barbican was steep and rocky. It ran between the two high, protective wooden palisade walls and it was hard to see anything. But Alaïs had taken this route out of the Cité many times, knew every dip and rise of the land, and she climbed down without difficulty.’

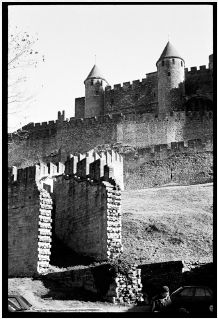

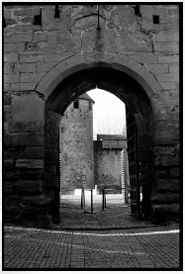

In the top right hand corner of the Place Saint-Gimer, is a long, steep cobbled ramp, signposted Grande Caponière. The Château Comtal, built into the western fortifications of the Cité, looms above you. Look up at the distinctive Tour Pinte watchtower – some 28 metres high – which points like a finger to the sky and belongs to the earliest phase of building of the Château. Taking it slowly, climb to the top of the ramp. Turn sharp left, then right, doubling back on yourself between the two sets of walls in the space between the outer and inner ring, known as the Lices.

Just before you go through the Porte d’Aude into the heart of the Cité itself, turn and look away northwest through the battlements. The flat land of Lauragais stretches before you towards Toulouse. The Montagne Noire National Park is to the right. Further west – if you are lucky – in winter and spring you will see the snow-capped Pyrenees. The Pic de Soularac – the site of the Labyrinth cave – is one of the highest you can see.

4

‘Every major city had an Inquisitional Court, from Tolosa to Carcassona. Once condemned, the Inquisitors turned their victims over to the secular authorities to be imprisoned, beaten, mutilated or burned. They kept their hands clean.’

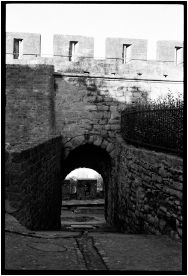

Once inside the walls, turn right into a narrow cobbled alleyway with a stone arch above it. The house on the corner here is the Maison de l’Inquisition. It used to have a footbridge from the first floor onto the ramparts, giving access to the Tour de la Justice where the Inquisitors kept their régistres – the records of their interrogations. On the stone walls inside, the twelve iron hooks – where the Dominican Friars hung the leather bags containing these forced testimonies – are still there.

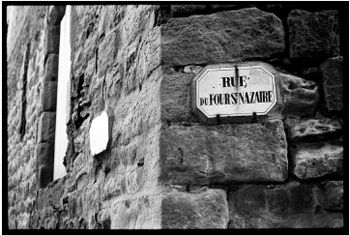

The alleyway – the rue du Four Saint-Nazaire – slopes quite steeply upwards, winding first left, then right, behind the kitchens of the Hôtel de la Cité.

5

‘It was the fin-de-siècle façade of the Hôtel de la Cité, understated but grand all the same, that caught her eye. Covered by ivy, with wroughtiron gates, arched stained-glass windows and deep red awnings the colour of ripe cherries, it whispered of money.’

The alleyway leads to the Place Saint-Nazaire. On the left are souvenir shops, on the right is the Hôtel de la Cité – which opened in 1909 on the site where the Bishop’s Palace once stood. Like her grandfather before her, it is the sumptuous accommodation that Marie-Cécile de l’Oradore chooses when she visits Carcassonne. She and Paul Authié share a meal in the impressive dining room.

6

Standing outside the Hôtel de la Cité, straight ahead is the Basilica Saint-Nazaire et Saint-Celse – ‘Sant Nasari’ as it was in Alaïs’ times. This is where Bertrand Pelletier hid the Book of Numbers, behind an unremarkable tomb. Of the 11th and 12th century church Alaïs and her father Bertrand knew, only the Romanesque nave remains. The rest was rebuilt in the gothic style on the orders of the French king Saint-Louis once the Trencavel lands had been finally subdued by the Crusaders. Today, there is even a memorial to a sermon preached by the founder of the Inquisition, St Dominic.

‘Kneeling down, Alaïs reached around behind the altar as Bertrand had shown her. She paddled her fingers over the surface of the wall. There was a soft click. Alaïs slowly, carefully, eased out the stone and slid it to one side, then stretched her hand into the dusty recess behind. She found the long, thin key, the metal dull with age and disuse, and put it into the lock of the wooden latticed door.’

7

‘The difference in age between the inner and outer walls was most evident here. The outer fortifications, which she read had been built at the end of the 13th century and restored during the 19th, were grey and the blocks were relatively equal in size. Alice felt a sense of peace after the noise within the Cité, a feeling of belonging here among such mountains and skies.’

Keeping the Basilica to your right – and the hideously grimacing gargoyles above you – follow the path and you will come out in another open square. To your left is the rue du Plô – to your right a gate and railings, the entrance to the amphitheatre where the Carcassonne summer festival stages dramatic son et lumière dramas.

Take the rue du Plô and walk uphill on the cobbles, past the school museum, past the little well – Place du Petit Puits – and make your way towards the bustle and noise of the central square, Place Marcou.

8

‘Alice let her feet guide her to the main square, Place Marcou. It was small and filled with restaurants and clipped plane trees. Their spreading branches, wide like entwined and sheltering hands above the tables and chairs, competed with the brightly coloured awnings. The names of the individual cafés were printed on the top – Le Marcou, Le Trouvère, Le Ménestrel.’

I have lost count of the number of times I have eaten in this square: toohot summer lunches under the lime trees, close evenings indoors with the fans turning, pizza in the hidden square by the fountain with buskers singing, bright cold winter mornings of milky coffee or sharp little black espressos and delicious butter croissants.

9

Leave Place Marcou along a narrow cobbled path in the northwest corner, next to Le Trouvère – the Occitan word for a troubadour.

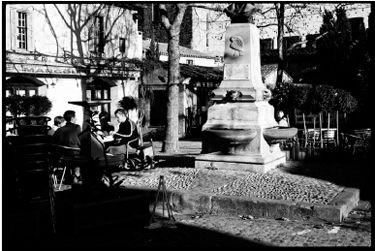

‘Alice strolled over the cobbles and out the other side, finding herself at the junction of the rue Cros-Mayrevieille and the Place du Château, where a triangle of shops, crêperies and restaurants surrounded a stone obelisk about eight feet high, topped by a bust of the nineteenth-century historian Jean-Pierre Cros-Mayrevieille.’

The monument is decorated with a bronze circlet of the Carcassonne battlements. Cros-Mayrevieille, a historian and important local administrator, who became inspector of historic monuments, inspired the listing and restoration of the Cité.

10

‘She walked forward until she was standing in front of a sweeping semicircular wall that protected the Château Comtal. Behind the imposing locked gates were the turrets and battlements of the castle. A fortress within a fortress. Alice stopped, realising that this had been her destination all along.’

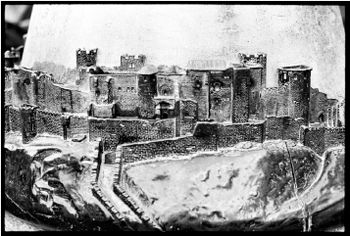

Ahead of you is the Château Comtal where Alaïs lived alongside her father Bertrand, her husband Guilhem and sister Oriane in the dynastic home of the Trencavel family. The semi-circular stone barbacane was added in the mid-13th century. The Château itself dates from the mid-12th century, constructed on the foundations of a much older castle. There are options to visiting the Château – a guided tour and the more restricted independent visit. For both, you pay at the kiosk just inside the gate.

Once inside, cross the flat stone bridge across a dry moat and enter through the Eastern Gatehouse into the Cour d’Honneur. In Viscount Trencavel’s time, a feudal elm stood in the centre of this main courtyard, mentioned in many documents and edicts of the time.

11

In the northwest corner of the Cour d’Honneur, in the shadow of the Tour de Degré, is where the chapel stood.

‘Alice looked down. Two raised bronze lines on the ground marked out the site of where a building had once stood. There was a row of letters. She crouched down and read that this had been the site of the chapel of the Château Comtal. Nothing remained.’

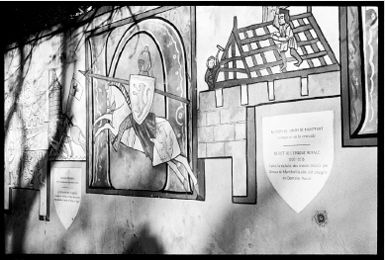

From the courtyard you can enter the Musée Lapidaire – the museum of stones – on the first floor of what used to be the Château’s living quarters. Walk through the museum to the third chamber. This is the Donjon Room – council chamber – or Round Room, so called because of its barrel-shaped ceiling. The beautiful 12th-century murals were only uncovered in 1926.

‘Alice looked up in admiration at the cerulean blue ceiling, faded and cracked, but beautiful still. On the panel to her left, two chevaliers were fighting, the one dressed in black, holding a round shield, destined to fall for ever more under the other’s lance.’

12

‘We’re ready for them, Messire. The Ciutat is well stocked. The hourds are completed to protect the walls from their sappers; all broken sections or points of weakness have been repaired and blocked; all the towers are manned.’

High up on the walls you will see modern reproductions of medieval hourds. These wooden galleries were designed to allow the defenders of the Château to attack invading forces, should the Cité itself be breached, and hurl projectiles down at them.

Viollet-le-Duc’s restoration of the Cité chose slate cones instead of flatter clay-tiled roofs, which have survived on the older Gallo-Roman towers. Detractors say that the 19th-century restoration transformed the Cité in the way Saint-Louis, the French king, would have wanted it.

13

‘Alaïs climbed up on the stone bench and reached for the lowest window of the Tour Pinte that gave on to the Cour du Midi. She hauled herself up, wriggled over the stone ledge and threaded herself in through the narrow gap. She was in luck. The room was empty.’

The Trencavels built the Château Comtal in the 12th century on Roman and Visigoth foundations as part of the western fortifications. Although most of the oldest buildings are gone – their stones scavenged to build the Bastide Saint-Louis – the Cour d’Honneur, the smaller Cour du Midi and the distinctive square watchtower, the Tour Pinte, remain. The watchtower – as all the defensive towers – had no stairs, just landings connected by wooden ladders that the guards could draw up after them.

14

It would be fun to leave the Château Comtal by the Western Gate, but it is locked. You must leave the same way you came in, past the ticket office.

Once outside the castle, turn left into rue Viollet-le-Duc, lined with restaurants and shops. Follow the road uphill to the big well at the Place du Grand Puits. Follow the road round to the right and go down past the Chambre d’Hôtes guest house. Take the second left into rue Notre-Dame, a charming cobbled street that leads down to the fortifications on the north side of the city. Make your way through the Porte de Rodez into the Lices – the open space between the twin rings of battlements.

‘The guards on duty at the Porte de Rodez were nodding most local people through without question, but stopping vagabonds and beggars, gypsies, Saracens and Jews, demanding to know their business in Carcassonne.’

The Porte de Rodez originally connected the Cité to the market garden suburb of Sant-Vicens. It was the first area to be attacked by the Crusaders at dawn on Monday 3rd August. Many people died here in 1209. Now, there are just the sharply sloping grassy banks . . .

15

Here is the possible short cut I promised you!

If you are tired, you can turn left here and follow the walls back round to the Porte d’Aude where you first entered the Cité. From there, you will be able to see the cobbled ramp leading down to Place Saint-Gimer and back to the Pont Vieux – the old bridge where you started.

If you are still feeling fit, turn to the right – keeping out of the way of the horse-drawn carriages – and follow the Lices round to the Porte Narbonnaise, the most important ceremonial entrance into the Cité. As you make your way along the dusty ground, glance up at the towers of the inner wall – some of the oldest stonework in Carcassonne is here, dating back to Gallo-Roman times. Of course, there was no outer ring in Alaïs’ day. Perhaps that is why she felt so insecure and tried to persuade her father Bertrand to let her take the Books to safety . . .

‘With respect, Paire, there is even more reason to let us go. If we don’t, the books will be trapped within the Ciutat. That cannot be what you want.’ She paused. He made no answer. ‘After everything you and Simeon and Esclarmonde have sacrificed, all the years of hiding, keeping the books safe, only to fail at the last.’

16

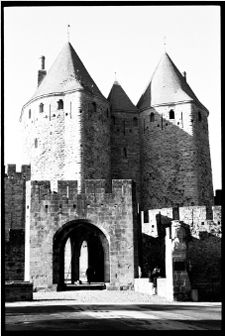

‘The crowds were several deep as they passed under the Trencavel coat of arms hanging between the two towers of the Porte Narbonnaise. Children ran alongside the horses, throwing flowers in their path and cheering.’

After about 200 metres you will reach the main gate into the Cité. Look up at the Tours de la Porte Narbonnaise to see the statue of the Virgin Mary that has replaced the Trencavel ensign.

Leave the Cité by the incongruous drawbridge – Pont-Levis – constructed by Viollet-le-Duc in his 19th-century restoration. Look out for the carved stone pillar with a bas relief of Dame Carcas, after whom, in the reign of the Emperor Charlemagne, the city was named. It reads Sum Carcas – ‘I am Carcas’.

17

Once outside the walls, you will find you have a view that extends for miles southeast towards Narbonne and the Mediterranean Sea. Turn left and look north and you will see Minervois, the pleasant downland through which the Crusaders marched on their way to besiege Carcassonne. If you come this way by night you will see clusters of lights folded in the hills; many of the villages they indicate saw combat or surrendered in fear of reprisals.

‘On his orders, the fugitives were dragged from their hiding place. He lifted his arm and thrust his blade into the parfait’s chest. For an instant, he held his gaze. The Frenchman’s flint grey eyes were stiff with contempt.’

In contrast, there is a lovely two-tiered 19th-century carousel on the piazza. I recommend the spinning teacups!

18

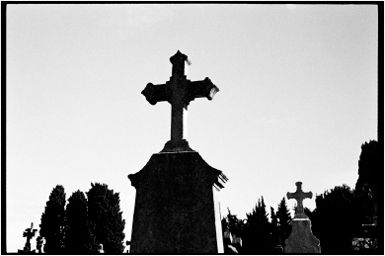

On the other side of the piazza from the carousel is the magnificent 19th-century cemetery where Jeanne Giraud is kidnapped and from which Alice escapes Paul Authié’s henchmen to head north to Chartres and her fateful meetings with Will, Marie-Cécile and François-Baptiste.

‘Alice walked slowly up the central aisle, feeling suddenly on edge. She found the atmosphere oppressive. Grey sculpted headstones, white porcelain cameos and black granite inscriptions marking birth and death, resting places bought by local families à perpétuité to mark their passing.’

In the summer, this is the place to find the calèches – open horse-drawn carriages – for a tour of the Cité.

19

As you emerge from the cemetery, recross the piazza past the carousel and take the path through the Jardin du Prado. It will bring you down to a roundabout. Take the first exit on the left – again downhill – onto rue Gustave-Nadaud. As you follow the pavement down, you will see, on the north wall to your right, a magnificent mural depicting the history of Carcassonne.

If you are still full of energy, you could explore the lovely – but busy with traffic – rue Trivalle, which runs parallel. Have a look at the wrought-iron gates of the church of Notre-Dame de l’Abbaye and the eclectic selection of shops, galleries and restaurants.

‘Even when she left the Cité and started to walk down rue Trivalle towards the main town, she felt just as nervous. No matter what she said to herself, she was sure someone was following her.’

20

From the bottom of rue Gustave-Nadaud – where it meets rue Trivalle – you will be able to see the Pont Vieux where your tour began. Walk up onto the pedestrianised old bridge and look down into the water. Imagine the salt mills moored in the current, the chevaliers’ chargers cooling off in the shallows after exercise . . . Imagine the Crusader encampment on the far bank . . .

Then turn and look up at the battlements of the Cité – once thought impregnable, then besieged and forced by treachery and intolerance to submit.

Yes, the stones of the Cité were conquered, but thanks to Alaïs, Sajhë, Alice, Audric and the rest – the sprit of this special place was victorious.