From a New York Times best-selling author, psychotherapist, and national advice columnist, a hilarious, thought-provoking, and surprising new book that takes us behind the scenes of a therapist’s world — where her patients are looking for answers (and so is she).One day, Lori Gottlieb is a therapist who helps patients in her Los Angeles practice. The next, a crisis causes her world to come crashing down. Enter Wendell, the quirky but seasoned therapist in whose office she suddenly lands. With his balding head, cardigan, and khakis, he seems to have come straight from Therapist Central Casting. Yet he will turn out to be anything but.

Contents

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Part One

Idiots

If the Queen Had Balls

The Space of a Step

The Smart One or the Hot One

Namast’ay in Bed

Finding Wendell

The Beginning of Knowing

Rosie

Snapshots of Ourselves

The Future Is Also the Present

Goodbye, Hollywood

Welcome to Holland

How Kids Deal with Grief

Harold and Maude

Hold the Mayo

The Whole Package

Without Memory or Desire

Part Two

Fridays at Four

What We Dream Of

The First Confession

Therapy with a Condom On

Jail

Trader Joe’s

Hello, Family

The UPS Guy

Embarrassing Public Encounters

Wendell’s Mother

Addicted

The Rapist

On the Clock

Part Three

My Wandering Uterus

Emergency Session

Karma

Just Be

Would You Rather?

The Speed of Want

Ultimate Concerns

Legoland

How Humans Change

Fathers

Integrity Versus Despair

My Neshama

What Not to Say to a Dying Person

Boyfriend’s Email

Wendell’s Beard

Part Four

The Bees

Kenya

Psychological Immune System

Counseling Versus Therapy

Deathzilla

Dear Myron

Mothers

The Hug

Don’t Blow It

It’s My Party and You’ll Cry if You Want To

Happiness Is Sometimes

Wendell

A Pause in the Conversation

Acknowledgments

About the Author

It is proposed that happiness be classified as a psychiatric disorder and be included in future editions of the major diagnostic manuals under the new name: major affective disorder, pleasant type. In a review of the relevant literature it is shown that happiness is statistically abnormal, consists of a discrete cluster of symptoms, is associated with a range of cognitive abnormalities, and probably reflects the abnormal functioning of the central nervous system. One possible objection to this proposal remains—that happiness is not negatively valued. However, this objection is dismissed as scientifically irrelevant.

—RICHARD BENTALL,Journal of Medical Ethics, 1992

The eminent Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung said this:“People will do anything, no matter how absurd,to avoid facing their own souls.”

But he also said this:

“Who looks inside, awakes.”

Author’s Note

This is a book that asks, “How do we change?” and answers with “In relation to others.” The relationships I write about here, between therapists and patients, require a sacred trust for any change to occur. In addition to attaining written permission, I have gone to great lengths to disguise identities and any recognizable details, and in some instances, material and scenarios from a few patients have been attributed to one. All changes were carefully considered and painstakingly chosen to remain true to the spirit of each story while also serving the greater goal: to reveal our shared humanity so that we can see ourselves more clearly. Which is to say, if you see yourself in these pages, it’s both coincidental and intentional.

A note on terminology: Those who come to therapy are referred to in various ways, most commonly as patients or clients. I don’t believe that either word quite captures the relationship I have with the people I work with. But the people I work with is awkward, and clients might be confusing, given that term’s many connotations, so for simplicity and clarity, I use patients throughout this book.

Part One

Nothing is more desirable than to be released from

an affliction, but nothing is more frightening

than to be divested of a crutch.

—James Baldwin

Idiots

Chart note, John:

Patient reports feeling “stressed out” and states that he is having difficulty sleeping and getting along with his wife. Expresses annoyance with others and seeks help “managing the idiots.”

Have compassion.

Deep breath.

Have compassion, have compassion, have compassion . . .

I’m repeating this phrase in my head like a mantra as the forty-year-old man sitting across from me is telling me about all of the people in his life who are “idiots.” Why, he wants to know, is the world filled with so many idiots? Are they born this way? Do they become this way? Maybe, he muses, it has something to do with all the artificial chemicals that are added to the food we eat nowadays.

“That’s why I try to eat organic,” he says. “So I don’t become an idiot like everyone else.”

I’m losing track of which idiot he’s talking about: the dental hygienist who asks too many questions (“None of them rhetorical”), the coworker who only asks questions (“He never makes statements, because that would imply that he had something to say”), the driver in front of him who stopped at a yellow light (“No sense of urgency!”), the Apple technician at the Genius Bar who couldn’t fix his laptop (“Some genius!”).

“John,” I begin, but he’s starting to tell a rambling story about his wife. I can’t get a word in edgewise, even though he has come to me for help.

I, by the way, am his new therapist. (His previous therapist, who lasted just three sessions, was “nice, but an idiot.”)

“And then Margo gets angry—can you believe it?” he’s saying. “But she doesn’t tell me she’s angry. She just acts angry, and I’m supposed to ask her what’s wrong. But I know if I ask, she’ll say, ‘Nothing,’ the first three times, and then maybe the fourth or fifth time she’ll say, ‘You know what’s wrong,’ and I’ll say, ‘No, I don’t, or I wouldn’t be asking! ’”

He smiles. It’s a huge smile. I try to work with the smile—anything to change his monologue into a dialogue and make contact with him.

“I’m curious about your smile just now,” I say. “Because you’re talking about being frustrated by many people, including Margo, and yet you’re smiling.”

His smile gets bigger. He has the whitest teeth I’ve ever seen. They’re gleaming like diamonds. “I’m smiling, Sherlock, because I know exactly what’s bothering my wife!”

“Ah!” I reply. “So—”

“Wait, wait. I’m getting to the best part,” he interrupts. “So, like I said, I really do know what’s wrong, but I’m not that interested in hearing another complaint. So this time, instead of asking, I decide I’m going to—”

He stops and peers at the clock on the bookshelf behind me.

I want to use this opportunity to help John slow down. I could comment on the glance at the clock (does he feel rushed in here?) or the fact that he just called me Sherlock (was he irritated with me?). Or I could stay more on the surface in what we call “the content”—the narrative he’s telling—and try to understand more about why he equates Margo’s feelings with a complaint. But if I stay in the content, we won’t connect at all this session, and John, I’m learning, is somebody who has trouble making contact with the people in his life.

“John,” I try again. “I wonder if we can go back to what just happened—”

“Oh, good,” he says, cutting me off. “I still have twenty minutes left.” And then he’s back to his story.

I sense a yawn coming on, a strong one, and it takes what feels like superhuman strength to keep my jaw clenched tight. I can feel my muscles resisting, twisting my face into odd expressions, but thankfully the yawn stays inside. Unfortunately, what comes out instead is a burp. A loud one. As though I’m drunk. (I’m not. I’m a lot of unpleasant things in this moment, but drunk isn’t one of them.)

Because of the burp, my mouth starts to pop open again. I squeeze my lips together so hard that my eyes begin to tear.

Of course, John doesn’t seem to notice. He’s still going on about Margo. Margo did this. Margo did that. I said this. She said that. So then I said—

During my training, a supervisor once told me, “There’s something likable in everyone,” and to my great surprise, I found that she was right. It’s impossible to get to know people deeply and not come to like them. We should take the world’s enemies, get them in a room to share their histories and formative experiences, their fears and their struggles, and global adversaries would suddenly get along. I’ve found something likable in literally everyone I’ve seen as a therapist, including the guy who attempted murder. (Beneath his rage, he turned out to be a real sweetheart.)

I didn’t even mind the week before, at our first session, when John explained that he’d come to me because I was a “nobody” here in Los Angeles, which meant that he wouldn’t run into any of his television-industry colleagues when coming for treatment. (His colleagues, he suspected, went to “well-known, experienced therapists.”) I simply tagged that for future use, when he’d be more open to engaging with me. Nor did I flinch at the end of that session when he handed me a wad of cash and explained that he preferred to pay this way because he didn’t want his wife to know he was seeing a therapist.

“You’ll be like my mistress,” he’d suggested. “Or, actually, more like my hooker. No offense, but you’re not the kind of woman I’d choose as a mistress . . . if you know what I mean.”

I didn’t know what he meant (someone blonder? Younger? With whiter, more sparkly teeth?), but I figured that this comment was just one of John’s defenses against getting close to anybody or acknowledging his need for another human being.

“Ha-ha, my hooker!” he said, pausing at the door. “I’ll just come here each week, release all my pent-up frustration, and nobody has to know! Isn’t that funny?”

Oh, yeah, I wanted to say, super-funny.

Still, as I heard him laugh his way down the hall, I felt confident that I could grow to like John. Underneath his off-putting presentation, something likable—even beautiful—was sure to emerge.

But that was last week.

Today he just seems like an asshole. An asshole with spectacular teeth.

Have compassion, have compassion, have compassion. I repeat my silent mantra then refocus on John. He’s talking about a mistake made by one of the crew members on his show (a man whose name, in John’s telling, is simply The Idiot) and just then, something occurs to me: John’s rant sounds eerily familiar. Not the situations he’s describing, but the feelings they evoke in him—and in me. I know how affirming it feels to blame the outside world for my frustrations, to deny ownership of whatever role I might have in the existential play called My Incredibly Important Life. I know what it’s like to bathe in self-righteous outrage, in the certainty that I’m completely right and have been terribly wronged, because that’s exactly how I’ve felt all day.

What John doesn’t know is that I’m reeling from last night, when the man I thought I was going to marry unexpectedly called it quits. Today I’m trying to focus on my patients (allowing myself to cry only in the ten-minute breaks between sessions, carefully wiping away my running mascara before the next person arrives). In other words, I’m dealing with my pain the way I suspect John has been dealing with his: by covering it up.

As a therapist, I know a lot about pain, about the ways in which pain is tied to loss. But I also know something less commonly understood: that change and loss travel together. We can’t have change without loss, which is why so often people say they want change but nonetheless stay exactly the same. To help John, I’m going to have to figure out what his loss would be, but first, I’m going to have to understand mine. Because right now, all I can think about is what my boyfriend did last night.

The idiot!

I look back at John and think: I hear you, brother.

Wait a minute, you might be thinking. Why are you telling me all this? Aren’t therapists supposed to keep their personal lives private? Aren’t they supposed to be blank slates who never reveal anything about themselves, objective observers who refrain from calling their patients names—even in their heads? Besides, aren’t therapists, of all people, supposed to have their lives together?

On the one hand, yes. What happens in the therapy room should be done on behalf of the patient, and if therapists aren’t able to separate their own struggles from those of the people who come to them, then they should, without question, choose a different line of work.

On the other hand, this—right here, right now, between you and me—isn’t therapy, but a story about therapy: how we heal and where it leads us. Like in those National Geographic Channel shows that capture the embryonic development and birth of rare crocodiles, I want to capture the process in which humans, struggling to evolve, push against their shells until they quietly (but sometimes loudly) and slowly (but sometimes suddenly) crack open.

So while the image of me with mascara running down my tear-streaked face between sessions may be uncomfortable to contemplate, that’s where this story about the handful of struggling humans you are about to meet begins—with my own humanity.

Therapists, of course, deal with the daily challenges of living just like everyone else. This familiarity, in fact, is at the root of the connection we forge with strangers who trust us with their most delicate stories and secrets. Our training has taught us theories and tools and techniques, but whirring beneath our hard-earned expertise is the fact that we know just how hard it is to be a person. Which is to say, we still come to work each day as ourselves—with our own sets of vulnerabilities, our own longings and insecurities, and our own histories. Of all my credentials as a therapist, my most significant is that I’m a card-carrying member of the human race.

But revealing this humanity is another matter. One colleague told me that when her doctor called with the news that her pregnancy wasn’t viable, she was standing in a Starbucks, and she burst into tears. A patient happened to see her, canceled her next appointment, and never came back.

I remember hearing the writer Andrew Solomon tell a story about a married couple he’d met at a conference. During the course of the day, he said, each spouse had confessed independently to him to taking antidepressants but didn’t want the other to know. It turned out that they were hiding the same medication in the same house. No matter how open we as a society are about formerly private matters, the stigma around our emotional struggles remains formidable. We’ll talk with almost anyone about our physical health (can anyone imagine spouses hiding their reflux medication from each other?), even our sex lives, but bring up anxiety or depression or an intractable sense of grief, and the expression on the face looking back at you will probably read, Get me out of this conversation, pronto.

But what are we so afraid of? It’s not as if we’re going to peer in those darker corners, flip on the light, and find a bunch of cockroaches. Fireflies love the dark too. There’s beauty in those places. But we have to look in there to see it.

My business, the therapy business, is about looking.

And not just with my patients.

A little-discussed fact: Therapists go to therapists. We’re required, in fact, to go during training as part of our hours for licensure so that we know firsthand what our future patients will experience. We learn how to accept feedback, tolerate discomfort, become aware of blind spots, and discover the impact of our histories and behaviors on ourselves and others.

But then we get licensed, people come to seek our counsel and . . . we still go to therapy. Not continuously, necessarily, but a majority of us sit on somebody else’s couch at several points during our careers, partly to have a place to talk through the emotional impact of the kind of work we do, but partly because life happens and therapy helps us confront our demons when they pay a visit.

And visit they will, because everyone has demons—big, small, old, new, quiet, loud, whatever. These shared demons are testament to the fact that we aren’t such outliers after all. And it’s with this discovery that we can create a different relationship with our demons, one in which we no longer try to reason our way out of an inconvenient inner voice or numb our feelings with distractions like too much wine or food or hours spent surfing the internet (an activity my colleague calls “the most effective short-term nonprescription painkiller”).

One of the most important steps in therapy is helping people take responsibility for their current predicaments, because once they realize that they can (and must) construct their own lives, they’re free to generate change. Often, though, people carry around the belief that the majority of their problems are circumstantial or situational—which is to say, external. And if the problems are caused by everyone and everything else, by stuff out there, why should they bother to change themselves? Even if they decide to do things differently, won’t the rest of the world still be the same?

It’s a reasonable argument. But that’s not how life generally works.

Remember Sartre’s famous line “Hell is other people”? It’s true—the world is filled with difficult people (or, as John would have it, “idiots”). I’ll bet you could name five truly difficult people off the top of your head right now—some you assiduously avoid, others you would assiduously avoid if they didn’t share your last name. But sometimes—more often than we tend to realize—those difficult people are us.

That’s right—sometimes hell is us.

Sometimes we are the cause of our difficulties. And if we can step out of our own way, something astonishing happens.

A therapist will hold up a mirror to patients, but patients will also hold up a mirror to their therapists. Therapy is far from one-sided; it happens in a parallel process. Every day, our patients are opening up questions that we have to think about for ourselves. If they can see themselves more clearly through our reflections, we can see ourselves more clearly through theirs. This happens to therapists when we’re providing therapy, and it happens to our own therapists too. We are mirrors reflecting mirrors reflecting mirrors, showing one another what we can’t yet see.

Which brings me back to John. Today, I’m not thinking about any of this. As far as I’m concerned, it’s been a difficult day with a difficult patient, and to make matters worse, I’m seeing John right after a young newlywed who’s dying of cancer—which is never an ideal time to see anyone, but especially not when you haven’t gotten much sleep, and your marriage plans have just been canceled, and you know that your pain is trivial compared to that of a terminally ill woman, and you also sense (but aren’t yet aware) that it’s not trivial at all because something cataclysmic is happening inside you.

Meanwhile, about a mile away, in a quaint brick building on a narrow one-way street, a therapist named Wendell is in his office seeing patients too. One after another, they’re sitting on his sofa, adjacent to a lovely garden courtyard, talking about the same kinds of things that my patients have been talking to me about on an upper floor of a tall glass office building. Wendell’s patients have seen him for weeks or months or perhaps even years, but I have yet to meet him. In fact, I haven’t even heard of him. But that’s about to change.

I am about to become Wendell’s newest patient.

If the Queen Had Balls

Chart note, Lori:

Patient in her mid-forties presents for treatment in the aftermath of an unexpected breakup. Reports that she seeks “just a few sessions to get through this.”

It all starts with a presenting problem.

By definition, the presenting problem is the issue that sends a person into therapy. It might be a panic attack, a job loss, a death, a birth, a relational difficulty, an inability to make a big life decision, or a bout of depression. Sometimes the presenting problem is less specific—a feeling of “stuckness” or the vague but nagging notion that something just isn’t quite right.

Whatever the problem, it generally “presents” because the person has reached an inflection point in life. Do I turn left or right? Do I try to preserve the status quo or move into uncharted territory? (Be forewarned: therapy will always take you into uncharted territory, even if you choose to preserve the status quo.)

But people don’t care about inflection points when they come for their first therapy session. Mostly, they just want relief. They want to tell you their stories, beginning with their presenting problem.

So let me fill you in on the Boyfriend Incident.

The first thing I want to say about Boyfriend is that he’s an extraordinarily decent human being. He’s kind and generous, funny and smart, and when he’s not making you laugh, he’ll drive to the drugstore at two a.m. to get you that antibiotic you just can’t wait until morning for. If he happens to be at Costco, he’ll text to ask if you need anything, and when you reply that you just need some laundry detergent, he’ll bring home your favorite meatballs and twenty jugs of maple syrup for the waffles he makes you from scratch. He’ll carry those twenty jugs from the garage to your kitchen, pack nineteen of them neatly into the tall cabinet you can’t reach, and place one on the counter, accessible for the morning.

He’ll also leave love notes on your desk, hold your hand and open doors, and never complain about being dragged to family events because he genuinely enjoys hanging out with your relatives, even the nosy or elderly ones. For no reason at all, he’ll send you Amazon packages full of books (books being the equivalent of flowers to you), and at night you’ll both curl up and read passages from them aloud to each other, pausing only to make out. While you’re binge-watching Netflix, he’ll rub that spot on your back where you have mild scoliosis, and when he stops, and you nudge him, he’ll continue rubbing for exactly sixty more delicious seconds before he tries to weasel out without your noticing (you’ll pretend not to notice). He’ll let you finish his sandwiches and sentences and sunscreen and listen so attentively to the details of your day that, like your personal biographer, he’ll remember more about your life than you will.

If this portrait sounds skewed, it is. There are many ways to tell a story, and if I’ve learned anything as a therapist, it’s that most people are what therapists call “unreliable narrators.” That’s not to say that they purposely mislead. It’s more that every story has multiple threads, and they tend to leave out the strands that don’t jibe with their perspectives. Most of what patients tell me is absolutely true—from their current points of view. Ask about somebody’s spouse while they’re both still in love, then ask about that same spouse post-divorce, and each time, you’ll get only half the story.

What you just heard about Boyfriend? That was the good half.

And now for the bad: It’s ten o’clock on a weeknight. We’re in bed, talking, and we’ve just decided which movie tickets to preorder for the weekend when Boyfriend goes strangely silent.

“You tired?” I ask. We’re both working single parents in our mid-forties, so ordinarily an exhausted silence would mean nothing. Even when we aren’t exhausted, sitting in silence together feels peaceful, relaxing. But if silence can be heard, tonight’s silence sounds different. If you’ve ever been in love, you know the kind of silence I’m talking about: silence on a frequency only your significant other can perceive.

“No,” he says. It’s one syllable but his voice shakes subtly, followed by more unsettling silence. I look over at him. He looks back. He smiles, I smile, and a deafening silence descends again, broken only by the rustling sound his twitching foot is making under the covers. Now I’m alarmed. In my office I can sit through marathon silences, but in my bedroom I last no more than three seconds.

“Hey, is something up?” I ask, trying to sound casual, but it’s a rhetorical question if ever there was one. The answer is obviously yes, because in the history of the world, nothing reassuring has ever followed this question. When I see couples in therapy, even if the initial response is no, in time the true answer is revealed to be some variation of I’m cheating, I maxed out the credit cards, my aging mother is coming to live with us, or I’m not in love with you anymore.

Boyfriend’s response is no exception.

He says: “I’ve decided that I can’t live with a kid under my roof for the next ten years.”

I’ve decided that I can’t live with a kid under my roof for the next ten years?

I burst out laughing. I know there’s nothing funny about what Boyfriend has said, but given that we’re planning to spend our lives together and I have an eight-year-old, it sounds so ridiculous that I decide it has to be a joke.

Boyfriend says nothing, so I stop laughing. I look at him. He looks away.

“What in the world are you talking about? What do mean, you can’t live with a kid for the next ten years?”

“I’m sorry,” he says.

“Sorry for what?” I ask, still catching up. “You mean you’re serious? You don’t want to be together?”

He explains that he does want to be together, but now that his teenagers are leaving for college soon, he’s come to realize that he doesn’t want to wait another ten years for the nest to be empty.

My jaw drops. Literally. I feel it open and hang in the air for a while. This is the first I’m hearing of this, and it takes a minute before my jaw is able to snap back into position so I can speak. My head is saying, Whaaaaaat? but my mouth says, “How long have you felt this way? If I hadn’t just asked if something was up, when were you going to tell me?” I think about how this can’t possibly be happening because just five minutes ago, we picked our movie for the weekend. We’re supposed to be together this weekend. At a movie!

“I don’t know,” he says sheepishly. He shrugs without moving his shoulders. His entire body is a shrug. “It never felt like the right time to bring it up.” (When my therapist friends hear this part of the story, they immediately diagnose him as “avoidant.” When my nontherapist friends hear it, they immediately diagnose him as “an asshole.”)

More silence.

I feel as though I’m viewing this scene from above, watching a confused version of myself move at incredible speed through the famous stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. If my laughter was denial and my when-the-hell-were-you-going-to-tell-me was anger, I’m moving on to bargaining. How, I want to know, can we make this work? Can I take on more of the childcare? Add an extra date night?

Boyfriend shakes his head. His teenagers don’t wake up at seven a.m. to play Legos, he says. He’s looking forward to finally having his freedom, and he wants to relax on weekend mornings. Never mind that my son plays independently with his Legos in the mornings. The problem, apparently, is that my son occasionally says this: “Look at my Lego! Look what I made!”

“The thing is,” Boyfriend explains, “I don’t want to have to look at the Legos. I just want to read the paper.”

I consider the possibility that an alien has invaded Boyfriend’s body or that he has a burgeoning brain tumor of which this personality shift is the first symptom. I wonder what Boyfriend would think of me if I broke up with him because his teenage daughters wanted me to look at their new leggings from Forever 21 when I was trying to relax and read a book. I don’t want to look at the leggings. I just want to read my book. What kind of person gets away with simply not wanting to look?

“I thought you wanted to marry me,” I say, pathetically.

“I do want to marry you,” he says. “I just don’t want to live with a kid.”

I think about this for a second, like a puzzle I’m trying to solve. It sounds like the riddle of the Sphinx.

“But I come with a kid,” I say, my voice getting louder. I’m furious that he’s bringing this up now, that he’s bringing this up at all. “You can’t order me up à la carte, like a burger without the fries, like a . . . a—” I think about patients who present ideal scenarios and insist that they can only be happy with that exact situation. If he didn’t drop out of business school to become a writer, he’d be my dream guy (so I’ll break up with him and keep dating hedge-fund managers who bore me). If the job wasn’t across the bridge, it would be the perfect opportunity (so I’ll stay in my dead-end job and keep telling you how much I envy my friends’ careers). If she didn’t have a kid, I’d marry her.

Certainly we all have our deal-breakers. But when patients repeatedly engage in this kind of analysis, sometimes I’ll say, “If the queen had balls, she’d be the king.” If you go through life picking and choosing, if you don’t recognize that “the perfect is the enemy of the good,” you may deprive yourself of joy. At first patients are taken aback by my bluntness, but ultimately it saves them months of treatment.

“The truth is, I didn’t want to date somebody with a kid,” Boyfriend is saying. “But then I fell in love with you, and I didn’t know what to do.”

“You didn’t fall in love with me before our first date, when I told you I had a six-year-old,” I say. “You knew what to do then, didn’t you?”

More suffocating silence.

As you’ve probably guessed, this conversation goes nowhere. I try to understand if it’s about something else—how could it not be about something else? After all, his wanting his freedom is the ultimate “It’s not you, it’s me” (always code for It’s not me, it’s you). Is Boyfriend unhappy with something in the relationship that he’s afraid to tell me about? I ask him calmly, my voice softer now, because I’m mindful of the fact that Very Angry People aren’t Very Approachable. But Boyfriend insists that it’s only about his wanting to live without kids, not without me.

I’m in a state of shock mixed with bewilderment. I don’t understand how this has never come up. How do you sleep soundly next to a person and plan a life with her when you’re secretly grappling with whether to leave? (The answer is simple—a common defense mechanism called compartmentalization. But right now I’m too busy using another defense mechanism, denial, to see it.)

Boyfriend, by the way, is an attorney, and he lays it all out as he would in front of a jury. He really does want to marry me. He really does love me. He just wants much more time with me. He wants to be able to leave spontaneously together for the weekend or come home from work and go out to eat without worrying about a third person. He wants the privacy of a couple, not the communal feel of a family. When he learned I had a young child, he told himself it wasn’t ideal, but he said nothing to me because he thought he could adjust. Two years later, though, as we’re about to merge our homes, just as his freedom is in sight, he’s realized how important this is. He knew things had to end, but he also didn’t want them to—and even when he thought about telling me, he didn’t know how to bring it up because of how far in we were already and how angry I’d likely be. He hesitated to tell me, he says, because he didn’t want to be a jerk.

The defense rests and is also very sorry.

“You’re sorry?” I spit out. “Well, guess what. By trying NOT to be a jerk, you’ve made yourself into the world’s BIGGEST jerk!”

He goes quiet again, and it hits me: His eerie silence earlier was his way of bringing this up. And although we go round and round on this until the sun peeks through the shutters, we both know in a bone-deep way that there’s nothing else to say.

I have a kid. He wants freedom. Kids and freedom are mutually exclusive.

If the queen had balls, she’d be the king.

Voilà—I had my presenting problem.

The Space of a Step

Telling somebody you’re a psychotherapist often leads to a surprised pause, followed by awkward questions like these: “Oh, a therapist! Should I tell you about my childhood?” Or “Can you help me with this problem with my mother-in-law?” Or “Are you going to psychoanalyze me?” (The answers, by the way, are “Please, don’t”; “Possibly”; and “Why would I do that here? If I were a gynecologist, would you ask if I was about to give you a pelvic exam?”)

But I understand where these responses come from. It boils down to fear—of being exposed, of being found out. Will you spot the insecurities that I’m so skillful at hiding? Will you see my vulnerabilities, my lies, my shame?

Will you see the human in my being?

It strikes me that the people I’m talking to at a barbecue or dinner party don’t seem to wonder whether they might see me and the qualities I, too, try to hide in polite company. Once they hear that I’m a therapist, I morph into somebody who might peer into their psyches if they aren’t careful to deflect the conversation with therapist jokes or walk away to refill a drink as soon as possible.

Sometimes, though, people will ask more questions, like “What kind of people do you see in your practice?” I tell them I see people just like any of us, which is to say, just like whoever is asking. Once I told a curious couple at a Fourth of July gathering that I see a good number of couples in my practice, and they proceeded to get into an argument right in front of me. He wanted to know why she seemed so interested in what a couples therapist does—after all, they weren’t having problems (uncomfortable chuckle). She wanted to know why he had no interest in the emotional lives of couples—after all, maybe they could use some help (glare). But was I thinking about them as a therapy case? Not at all. This time, I was the one who left the conversation to “get a refill.”

Therapy elicits odd reactions because, in a way, it’s like pornography. Both involve a kind of nudity. Both have the potential to thrill. And both have millions of users, most of whom keep their use private. Though statisticians have attempted to quantify the number of people in therapy, their results are thought to be skewed because many people who go to therapy choose not to admit it.

But those underreported numbers are still high. In any given year, some thirty million American adults are sitting on clinicians’ couches, and the United States isn’t even the world leader in therapy. (Fun fact: the countries with the most therapists per capita are, in descending order, Argentina, Austria, Australia, France, Canada, Switzerland, Iceland, and the United States.)

Given that I’m a therapist, you’d think that the morning after the Boyfriend Incident, it might occur to me to see a therapist myself. I work in a suite of a dozen therapists, my building is full of therapists, and I’ve belonged to several consultation groups in which therapists discuss their cases together, so I’m well versed in the therapy world.

But as I lie paralyzed in the fetal position, that’s not the call I make.

“He’s trash!” my oldest friend, Allison, says after I tell her the story from my bed before my son wakes up. “Good riddance! What kind of person does that—not just to you, but to your kid?”

“Right!” I agree. “Who does this?” We spend about twenty minutes bashing Boyfriend. During an initial burst of pain, people tend to lash out either at others or at themselves, to turn the anger outward or inward. Allison and I are choosing outward, baby! She’s in the Midwest, commuting to work, two hours ahead of me here on the West Coast, and she gets right to the point.

“You know what you should do?” she says.

“What?” I feel like I’ve been stabbed in the heart, and I’ll do anything to stop the pain.

“You should go sleep with somebody! Go sleep with somebody and forget about the Kid Hater.” I instantly love Boyfriend’s new name: the Kid Hater. “Clearly he wasn’t the person you thought he was. Go take your mind off of him.”

Married for twenty years to her college sweetheart, Allison has no idea how to give guidance to single people.

“It might help you bounce back faster, like falling off a bike and then getting right back on,” she continues. “And don’t roll your eyes.”

Allison knows me well. I’m rolling my red, stinging eyes.

“Okay, I’ll go sleep with someone,” I squeak out, knowing she’s trying to make me laugh. But then I’m sobbing again. I feel like a sixteen-year-old going through her first breakup, and I can’t believe I’m having this reaction in my forties.

“Oh, hon,” Allison says, her voice like a hug. “I’m here, and you’ll get through this.”

“I know,” I say, except that in a strange way, I don’t. There’s a popular saying, a paraphrase of a Robert Frost poem: “The only way out is through.” The only way to get to the other side of the tunnel is to go through it, not around it. But I can’t even picture the entrance right now.

After Allison parks her car and promises to call at her first break, I look at the clock: 6:30 a.m. I call my friend Jen, who’s a therapist with a practice across town. She picks up on the first ring and I hear her husband in the background asking who it is. Jen whispers, “I think it’s Lori?” She must have seen the caller ID, but I’m crying so hard I haven’t even said hello yet. If it weren’t for caller ID, she’d think I was some sicko prank-calling.

I catch my breath and tell her what happened. She listens attentively. She keeps saying that she can’t believe it. We also spend twenty minutes trashing Boyfriend, and then I hear her daughter enter the room and say that she needs to get to school early for swim practice.

“I’ll call you at lunch,” Jen says. “But in the meantime, I don’t know that this is the end of the story. Something’s screwy. Unless he’s a sociopath, it doesn’t jibe at all with what I saw for the past two years.”

“Exactly,” I say. “Which means he’s a sociopath.”

I hear her take a sip of water and put the glass down.

“In that case,” she says, swallowing, “I have a great guy for you—one who’s not a kid hater.” She also likes Boyfriend’s new name. “In a few weeks, when you’re ready, I want to introduce you.”

I almost smile at the preposterousness of this. What I really need just hours into this breakup is for somebody to sit with me in my pain, but I also know how helpless it feels to watch a friend suffer and do nothing to fix it. Sitting-with-you-in-your-pain is one of the rare experiences that people get in the protected space of a therapy room, but it’s very hard to give or get outside of it—even for Jen, who is a therapist.

When we’re off the phone, I think about her “in a few weeks” comment. Could I really go on a date in just a few weeks? I imagine being out with a well-meaning guy who’s doing his best to make first-date conversation; without knowing it, he’ll make a reference to something that reminds me of Boyfriend (pretty much everything will remind me of Boyfriend, I’m convinced), and I won’t be able to hold back tears. Crying on a first date is decidedly a turnoff. A therapist crying on a first date is both a turnoff and alarming. Besides, I have the bandwidth to focus only on the immediate present.

Right now it’s all about one foot, then the other.

That’s one thing I tell patients who are in the midst of crippling depression, the kind that makes them think, There’s the bathroom. It’s about five feet away. I see it, but I can’t get there. One foot, then the other. Don’t look at all five feet at once. Just take a step. And when you’ve taken that step, take one more. Eventually you’ll make it to the shower. And you’ll make it to tomorrow and next year too. One step. They may not be able to imagine their depression lifting anytime soon, but they don’t need to. Doing something prompts you to do something else, replacing a vicious cycle with a virtuous one. Most big transformations come about from the hundreds of tiny, almost imperceptible, steps we take along the way.

A lot can happen in the space of a step.

Somehow I manage to wake my son, prepare breakfast, pack his lunch, make conversation, drop him at school, and drive to work, all without shedding a tear. I can do this, I think as I ride the elevator up to my office. One foot, then the other. One fifty-minute session at a time.

I enter my suite, say hello to colleagues in the hallway, unlock the door to my office, and go through my routine: I put away my belongings, turn off the phone ringers, unlock the files, and fluff the pillows on the couch. Then, uncharacteristically, I take a seat on it myself. I look at my empty therapist chair and consider the view from this side of the room. It’s oddly comforting. I stay there until the tiny green light by the door flicks on, letting me know that my first patient is here.

I’m ready, I think. One foot, then the other. I’m going to be fine.

Except that I’m not.

The Smart One or the Hot One

I’ve always been drawn to stories—not just what happens, but how the story is told. When people come to therapy, I’m listening to their narratives but also for their flexibility with them. Do they consider what they’re saying to be the only version of the story—the “accurate” version—or do they know that theirs is just one of many ways to tell it? Are they aware of what they’re choosing to leave in or out, of how their motivation in sharing this story affects how the listener hears it?

I thought a lot about those questions in my twenties—not in relation to therapy patients, but in relation to movie and TV characters. That’s why, as soon as I graduated from college, I got a job in the entertainment business, or what everyone called, simply, “Hollywood.”

This job was at a large talent agency, and I worked as the assistant to a junior film agent who, like many people in Hollywood, wasn’t much older than me. Brad represented screenwriters and directors, and he was so boyish-looking, with his smooth cheeks and mop of floppy hair he’d constantly swat from his eyes, that his fancy suits and expensive shoes always seemed too mature for him, like he was wearing his father’s clothing.

Technically, my first day on the job was a trial. I’d been told by Gloria in human resources (I never learned her last name; everyone called her “Gloria-in-human-resources”) that Brad had narrowed down his assistant candidates to two finalists, and each of us would work for a day as a test run. On the afternoon of mine, returning from the Xerox room, I overheard my prospective boss and another agent, his mentor, talking in his office.

“Gloria-in-human-resources wants an answer by tonight,” I heard Brad say. “Should I pick the smart one or the hot one?”

I froze, appalled.

“Always pick the smart one,” the other agent replied, and I wondered which one Brad considered me to be.

An hour later, I got the job. And despite finding the question outrageously inappropriate, I felt perversely hurt.

Still, I wasn’t sure why Brad had pegged me as smart. All I’d done that day was dial a string of phone numbers (repeatedly disconnecting calls by pressing the wrong buttons on the confusing phone system), make coffee (which was sent back twice), Xerox a script (I pushed 10 instead of 1 for number of copies, then hid the nine extra screenplays under a couch in the break room), and trip over a lamp cord in Brad’s office and fall on my ass.

The hot one, I concluded, must have been particularly stupid.

Technically, my position was “motion-picture literary assistant,” but really I was a secretary who rolled the call list all day, dialing the numbers of studio executives and filmmakers, telling each person’s assistant that my boss was on the line, then patching my boss through. It was widely known in the industry that assistants were expected to listen in silently on these calls so that we’d know what scripts had to be sent where without the need for instructions later. Sometimes, though, the parties on the calls would forget about us, and we’d hear all kinds of juicy gossip about our bosses’ famous friends—who’d had an argument with a spouse or which studio executive was “very confidentially” about to be sent to “producers pasture,” shorthand for being given a vanity production deal on the studio lot. If the person my boss was trying to reach wasn’t available, I’d “leave word” and move on to the next name on the hundred-person call sheet, sometimes being instructed to strategically return calls at inopportune times (before nine thirty a.m., because nobody in Hollywood arrived at work before ten, or, less subtly, during lunch) in order to miss the person on purpose.

Although the movie world was glamorous—Brad’s Rolodex was filled with the home numbers and addresses of people I’d admired for years—the job of an assistant was its opposite. As an assistant, you fetched coffee, made haircut and pedicure appointments, picked up dry cleaning, screened calls from parents or exes, Xeroxed and messengered documents, took cars to the mechanic, ran personal errands, and always, without fail, brought chilled bottled water into every meeting (never saying a word to the writers or directors present, whom you were dying to meet).

Finally, late at night, you’d type up ten pages of single-spaced notes on scripts that came in from the agency’s clients so that your boss could make insightful comments in meetings the next day without having to read anything. We assistants put a lot of effort into those script notes in order to demonstrate that we were bright and capable and could one day (please, God!) stop doing assistant work, with its mind-numbing duties, long hours, minimal pay, and no overtime compensation.

A few months into the job, it became apparent that while the hot ones at my agency got all the attention—and there were many hot ones in the assistant pool—the smart ones got assigned all the extra work. In my first year there, I slept very little because I was reading and writing comments on a dozen scripts a week—all after hours and on weekends. But I didn’t mind. In fact, that was my favorite part of the job. I learned how to craft stories and fell in love with fascinating characters with complicated inner lives. As the months went by, I got slightly more confident in my instincts, less worried about sharing a silly story idea.

Soon I was hired as an entry-level film executive at a production company, with the title story editor; here I got to participate in meetings while another assistant brought in the bottled water. I worked closely with writers and directors, hunkering down in a room and going over material scene by scene, helping to make changes the studio wanted without having the writers, who often felt protective of their material, fly into a rage or threaten to quit the project. (These negotiations would turn out to be great practice for couples therapy.)

Sometimes, to avoid distractions at the office, I’d work with filmmakers early in the morning in my tiny starter apartment, picking up breakfast snacks the night before while thinking, John Lithgow is going to be eating this bagel in my crappy living room with the hideous wall-to-wall carpet and popcorn ceilings tomorrow! Could it get any better than this?

And then it did—or so I thought. I got promoted. It was a promotion I’d worked hard for and wanted very badly. Until I actually got it.

The irony of my job was that a lot of the creative work happens when you don’t have much experience. When you’re just starting out, you’re the behind-the-scenes person, the one who does all the script work at the office while the higher-level people are out wooing talent, lunching with agents, or stopping by movie sets to check in on the company’s productions. When you become a development executive, you go from being what’s known as an internal executive to an external one, and if you were the social kid in high school, this is the job for you. But if you were the bookish kid who was happiest working intently with a couple of friends in the library, be careful what you wish for.

Now I was out awkwardly attempting to socialize at lunches and meetings all day. On top of that, the pace of the process began to feel glacial. It could take ages—literally years—for a film to be made, and I got the sinking feeling that I was in the wrong job. I’d moved into a duplex with a friend, and she pointed out that I’d been watching a lot of TV every night. Like, in a pathological way.

“You seem depressed,” she said with concern. I said I wasn’t depressed; I was just bored. I hadn’t considered that if the only thing that keeps you going all day is knowing you’ll get to turn on the TV after dinner, you probably are depressed.

One day around this time, I was sitting at lunch in a perfectly nice restaurant with a perfectly lovely agent who was talking about a perfectly good deal she had made when I noticed that four words kept running through my mind: I. Just. Don’t. Care. No matter what the agent said, these four words played in a loop, and they didn’t stop when the check came, nor did they stop on the drive back to the office. They rattled around in my head the next day, too, and for the next several weeks, until finally I had to admit, months later, that they weren’t going away. I. Just. Don’t. Care.

And since the only thing I did seem to care about was watching TV—since the only time I felt anything (or, perhaps more accurately, the only time I felt the absence of something unpleasant that I couldn’t quite put my finger on) was when I was immersed in these imaginary worlds with new episodes arriving weekly like clockwork—I applied for a job in television. Within a few months, I began working in series development at NBC.

It felt like a dream come true. I thought, I’ll get to help tell stories again. Even better, instead of developing self-contained films with neatly crafted endings, I’ll get to work on series. Over the course of multiple episodes and seasons, I’ll have a hand in helping audiences get to know their favorite characters, layer by layer—characters as flawed and contradictory as the rest of us, with stories that are just as messy.

It seemed like the perfect solution to my boredom. It would take years for me to realize that I’d solved the wrong problem.

Namast’ay in Bed

Chart note, Julie:

Thirty-three-year-old university professor presents for help in dealing with cancer diagnosis upon returning from her honeymoon.

“Is that a pajama top?” Julie asks as she walks into my office. It’s the afternoon after the Boyfriend Incident, right before my appointment with John (and his idiots), and I’ve almost made it through the day.

I give her a quizzical look.

“Your shirt,” she says, settling onto the couch.

I flash back to the morning, to the gray sweater I intended to wear and then, with a sinking feeling, to the image of the sweater laid out on my bed next to the gray pajama top I’d taken off before stepping into the shower in my post-breakup daze.

Oh God.

On one of his Costco runs, Boyfriend had gotten me a pack of PJs, their fronts emblazoned with sayings like AREN’T I JUST A FUCKING RAY OF SUNSHINE and TALK NERDY TO ME and ZZZZZZZZZZ SNORE (not the message a therapist wants to send her patients). I’m trying to remember which one I wore last night.

I brace myself and glance down. My top says NAMAST’AY IN BED. Julie is looking at me, waiting for an answer.

Whenever I’m not sure what to say in the therapy room—which happens to therapists more often than patients realize—I have a choice: I can say nothing until I understand the moment better, or I can attempt an answer, but whatever I do, I must tell the truth. So while I’m tempted to say that I do yoga and that my top is simply a casual T-shirt, both would be lies. Julie does yoga as part of her Mindful Cancer program, and if she starts talking about various poses, I’d have to lie further and pretend that I’m familiar with them—or admit that I lied.

I remember when, during my training, a fellow intern told a patient he would be out of the clinic for three weeks, and she asked where he was going.

“I’m going to Hawaii,” the intern said truthfully.

“For vacation?” the patient asked.

“Yes,” he replied, even though, technically, he was going for his wedding, which was to be followed by a two-week island honeymoon.

“That’s a long vacation,” the patient remarked, and the intern, believing that sharing the news of his wedding would be too personal, decided instead to focus on the patient’s comment. What would it be like for her to miss three weeks of sessions? What did her feelings about his absence remind her of? Both of which might be fruitful avenues to explore, but so would the patient’s indirect question: Since it’s neither summer nor a holiday season, why are you really taking three weeks off? And sure enough, when the intern returned to work, the patient noticed his wedding ring and felt betrayed: “Why didn’t you just tell me the truth?”

In retrospect, the intern wished he had. So what if a patient learned that he was getting married? Therapists get married and patients have reactions to that. Those can be worked through. Loss of trust is harder to repair.

Freud argued that “the physician should be impenetrable to the patient, and like a mirror, reflect nothing but what is shown to him.” Nowadays, though, most therapists use some form of what’s known as self-disclosure in their work, whether it’s sharing some of their own reactions that come up during the session or acknowledging that they watch the TV show that a patient keeps referring to. (Better to admit that you watch The Bachelor than to feign ignorance and slip up by naming a cast member the patient hasn’t mentioned yet.)

Inevitably, though, the question of what to share gets tricky. One therapist I know told a patient whose child was diagnosed with Tourette’s syndrome that she, too, had a son with Tourette’s—and it deepened their relationship. Another colleague treated a man whose father had committed suicide but never revealed to the patient that his own father had also committed suicide. In each situation, there’s a calculation to make, a subjective litmus test we use to assess the value of the disclosure: Is this information helpful for the patient to have?

When done well, self-disclosure can bridge some distance with patients who feel isolated in their experiences, and it can encourage more openness. But if it’s perceived as inappropriate or self-indulgent, the patient will feel uncomfortable and start to shut down—or simply flee.

“Yes,” I tell Julie. “It’s a pajama top. I guess I put it on by mistake.”

I wait, wondering what she’ll say. If she asks why, I’ll tell the truth (although not the specifics): I wasn’t paying attention this morning.

“Oh,” she says. Then her mouth twitches the way it does when she’s about to cry, but instead, she starts laughing.

“I’m sorry, I’m not laughing at you. Namast’ay in Bed . . . that’s exactly how I feel!”

She tells me about a woman in her Mindful Cancer program who’s convinced that if Julie doesn’t take yoga seriously—along with the famous pink ribbons and the optimism—her cancer will kill her. Never mind that Julie’s oncologist has already informed her that her cancer will kill her. This woman still insists it can be cured with yoga.

Julie despises her.

“Imagine if I walked into yoga wearing that top and—”

Now she’s laughing uncontrollably, reining it in and then bursting out with another round. I haven’t seen Julie laugh once since she learned she was dying. This must be what she was like in what she calls “B.C.” or “Before Cancer,” when she was happy and healthy and falling in love with her soon-to-be husband. Her laughter is like a song, and it’s so contagious that I start laughing too.

We both sit there laughing, her at the sanctimonious woman, and me at my mistake—at the ways in which our minds betray us as much as our bodies do.

Julie discovered her cancer while having sex with her husband on a beach in Tahiti. She didn’t suspect it was cancer, though. Her breast felt tender, and later, in the shower, the tender spot felt funky, but often she had areas that felt funky and her gynecologist always found them to be glands that changed size at certain times of the month. Anyway, she thought, maybe she was pregnant. She and her new husband, Matt, had been together for three years and both had talked about wanting to start a family as soon as they got married. In the weeks before the wedding, they hadn’t been vigilant about birth control.

It was a good time to have a baby too. Julie had just gotten tenure at her university, and after years of hard work, she could finally take a breath. Now there would be more time for her passions: running marathons and climbing mountains and baking silly cakes for her nephew. There would also be time for marriage and parenthood.

When Julie got back from her honeymoon, she peed on a stick and showed it to Matt, who picked her up and danced around the room with her. They decided that the song that happened to be on the radio—“Walking on Sunshine”—would be their baby’s theme song. Excited, they went to the obstetrician for their first prenatal appointment, and when her doctor felt the “gland” that Julie had noticed on her honeymoon, his smile faded slightly.

“It’s probably nothing,” he said, “but let’s get it checked out.”

It wasn’t nothing. Young, newly married, and pregnant, with no family history of breast cancer, Julie had been struck by the randomness of the universe. Then, while grappling with how to handle the cancer treatment and the pregnancy, she had a miscarriage.

This was when Julie landed in my office.

It was an odd referral, given that I wasn’t a therapist who specialized in treating people with cancer. But my lack of expertise was exactly why Julie wanted to see me. She had told her physician that she didn’t want a therapist from “the cancer team.” She wanted to feel normal, to be part of the living. And since her doctors seemed confident that she’d be fine after surgery and chemo, she wanted to focus on both getting through the treatment and being newly married. (What should she say in her wedding-gift thank-you notes? Thanks so much for the lovely bowl . . . I keep it by my bed to vomit in?)

The treatment was brutal but Julie got better. The day after her doctors declared her “tumor-free,” she and Matt went on a hot-air balloon ride with their closest friends and family. It was the first week of summer, and as they joined arms and watched the sunset from a thousand feet above the earth, Julie no longer felt cheated, as she had during the treatment, but lucky. Yes, she’d gone through hell. But it was behind her, and her future lay ahead. In six months, she would get a final scan, a sign-off, to clear her for pregnancy. That night, she dreamed that she was in her sixties and holding her first grandchild.

Julie was in good spirits. Our work was done.

I didn’t see Julie between the hot-air balloon ride and the scan. But I did start getting calls from other cancer patients who’d been referred by Julie’s oncologist. There’s nothing like illness to take away a sense of control, even if we often have less of it than we imagine. What people don’t like to think about is that you can do everything right—in life or in a treatment protocol—and still get the short end of the stick. And when that happens, the only control you have is how you deal with that stick—your way, not the way others say you should. I’d let Julie do it her way—I was so inexperienced that I didn’t have a strong sense of what a “way” should look like—and it seemed to help.

“Whatever you did with her,” Julie’s oncologist said, “she seemed pleased with the outcome.”

I knew that I hadn’t done anything brilliant with Julie. Mostly, I worked hard not to flinch from her rawness. But that rawness went only so far because we weren’t even thinking about death then. Instead, we discussed wigs versus scarves, sex and postsurgery body image. And I helped her think through how to manage her marriage, parents, and work, much the way I might with any patient.

Then one day I checked my messages and heard Julie’s voice. She wanted to see me right away.

She came in the next morning, ashen. The scan that was supposed to show nothing had instead found a rare form of cancer, different from the original. In all likelihood, this cancer was going to kill her. It might take a year or five or, if things went very well, ten. Of course, they would explore experimental treatments, but they were just that—experimental.

“Will you stay with me until I die?” Julie asked, and though my instinct was to do what people tend to do whenever somebody brings up death, which is to deny death completely (Oh, hey, let’s not go there yet. Those experimental treatments might work), I had to remember that I was there to help Julie, not comfort myself.

Still, at the moment she asked, I was stunned, still absorbing the news. I wasn’t sure I was the best person for this. What if I said or did the wrong thing? Would I offend her if my feelings—discomfort, fear, sadness—came across in my facial expressions or body language? She was going to get only one chance at doing this the way she wanted. What if I let her down?

She must have seen my hesitation.

“Please,” she said. “I know it’s not a picnic, but I can’t go to those cancer people. It’s like a cult. They call everyone ‘brave,’ but what choice do we have, and besides, I’m terrified and still cringe at the sight of the needles like I did as a kid getting my shots. I’m not brave and I’m not a warrior fighting a battle. I’m just an ordinary college professor.” She leaned forward on the couch. “They have affirmations on their walls. So, please?”

Looking at Julie, I couldn’t say no. More important, now I didn’t want to.

And right then, the nature of our work together changed: I was going to help her come to terms with her death.

This time, my inexperience might matter.

Finding Wendell

“Maybe you should talk to someone,” Jen suggests two weeks after the breakup. She has just called to check on me at work. “You need to find a place where you’re not being a therapist,” she adds. “You need to go where you can completely fall apart.”

I look at myself in the mirror that hangs by the door in my office, the one I use to make sure I don’t have lipstick on my teeth when I’m about to retrieve a patient from the waiting room after a quick snack between sessions. I appear normal, but I feel dizzy and disoriented. I’m fine with patients—seeing patients is a relief, a full fifty minutes of respite from my own life—but outside of sessions, I’m losing it. In fact, as each day goes by, I seem worse, not better.

I can’t sleep. I can’t concentrate. Since the breakup, I’ve left my credit card at Target, driven out of the gas station with my tank’s cap hanging off, and fallen off a step in my garage, badly bruising my knee. My chest hurts as if my heart has been crushed, though I know it hasn’t been, because if anything, my heart is working harder, beating rapidly 24/7—a sign of anxiety. I obsess about Boyfriend’s state of mind, which I imagine is calm and unconflicted, while I lie on my bedroom floor at night and miss him. Then I obsess about whether I really miss him—did I even know him? Do I miss him, or do I miss the idea of him?

So when Jen says I should see a therapist, I know she’s right. I need someone to help me through this crisis.

But who?

Finding a therapist is a tricky thing. It’s not like looking for, say, a good internist or dentist because pretty much everyone needs an internist or dentist. A therapist, though? Consider:

If you ask somebody for a therapist recommendation and that person isn’t seeing a therapist, he or she might be offended that you’d made that assumption. Similarly, if you ask somebody for a therapist recommendation and that person is seeing a therapist, he or she might be upset that it was so apparent to you. Of all the people she knows, this person might wonder, why did she think to ask me?

When you inquire, you risk this person asking why you want to see a therapist. “What’s wrong?” this person might say. “Is it your marriage? Are you depressed?” Even if people don’t ask this aloud, every time they see you, they might be silently wondering, What’s wrong? Is it your marriage? Are you depressed?

If your friend does give you her therapist’s name, there might be unexpected checks and balances to what you say in the therapy room. If, for instance, your friend recounts to this therapist a not-so-flattering incident that involves you, and you give a different version of this same incident—or omit it altogether—the therapist will see you in a way you haven’t chosen to present. But you won’t know what the therapist knows about you, because the therapist can’t mention anything said in somebody else’s session.

These caveats notwithstanding, word of mouth is often an effective way to find a therapist. You can also go on PsychologyToday.com and sort through profiles in your area. But however you do it, you may need to meet with a few before you find the right one. That’s because clicking with your therapist matters in a way that it doesn’t with other clinicians (as another therapist said: “It’s not the same as choosing a good cardiologist who sees you maybe twice a year and will never know about your massive insecurity”). Study after study shows that the most important factor in the success of your treatment is your relationship with the therapist, your experience of “feeling felt.” This matters more than the therapist’s training, the kind of therapy they do, or what type of problem you have.

But I have unique constraints in finding a therapist. To avoid an ethical breach known as a dual relationship, I can’t treat or receive treatment from any person in my orbit—not a parent of a kid in my son’s class, not the sister of my coworker, not a friend’s mom, not my neighbor. The relationship in the therapy room needs to be its own, distinct and apart. These rules don’t hold for other health-care clinicians. You can play tennis or be in a book club with your surgeon, dermatologist, or chiropractor, but not with your therapist.

This narrows my prospects dramatically. I’m friendly with, refer patients to, go to conferences with, or otherwise associate with numerous therapists in town. On top of that, my friends who are therapists, like Jen, know many of the same therapists I do. Even if Jen referred me to one of her colleagues that I don’t know, there would be something awkward about her being friendly with my therapist—it’s too close. And as for my asking my colleagues? Well, there’s this: I don’t want my colleagues to know I’m seeking urgent therapy. Might they hesitate, consciously or not, to send referrals my way?

So while I’m surrounded by therapists, my predicament conjures that Coleridge line “Water, water, everywhere / Nor any drop to drink.”

But by the end of the day, I have an idea.

My colleague Caroline isn’t in my suite, or even in my building. She’s not a friend, although we’re professionally friendly. Sometimes we share cases—I’ll see a couple, and she’ll see one of the members of the couple individually, or vice versa. Any referral she’d have, I’d trust.

I dial her cell at ten to the hour, and she picks up.

“Hi, how are you?” she asks.

I say I’m great. “Absolutely great,” I repeat enthusiastically. I don’t mention the fact that I’ve barely slept or eaten and feel like I might faint. I ask how she is, then get right to the point.

“I need a referral,” I say, “for a friend.”

I quickly explain that this “friend” is looking specifically for a male therapist to keep Caroline from wondering why I’m not referring my friend to her.

Through the phone, I can almost hear the gears turning in her head. About three-fourths of clinicians who do therapy (as opposed to research, psychological testing, or medication management) are women, so it takes some thought for her to find a man. I add that the one male therapist in my office suite, who happens to be one of the most talented therapists I know, won’t work out for this friend because this friend doesn’t feel comfortable doing therapy at my office, where we share a waiting room.

“Hmm,” Caroline says. “Let me think. It’s a male patient who wants the referral?”

“Yes, he’s in his forties,” I say. “High-functioning.”

High-functioning is therapist code for “a good patient,” the kind most therapists enjoy working with, often to balance out the patients we also want to work with but who are less high-functioning. High-functioning patients are those who can form relationships, manage adult responsibilities, and have a capacity for self-reflection. The kind who don’t call daily between sessions with emergencies. Studies show, and common sense dictates, that most therapists prefer to work with patients who are verbal, motivated, open, and responsible—these are the patients who improve more quickly. I include the high-functioning bit with Caroline because it broadens the range of therapists who might be interested in this case, and, well, I consider myself to be relatively high-functioning. (At least, I did until recently.)

“I think he’d feel more comfortable with a male therapist who’s also married with kids,” I continue.

I add this for a reason too. I know this isn’t a fair assumption, but I’m afraid that a female therapist might be predisposed to empathize with me post-breakup and that a male therapist who’s neither married nor a father won’t understand the nuances of the kid part of the situation. In short, I want to see if an objective male professional who has firsthand experience of marriage and kids—a man just like Boyfriend—will be as appalled at Boyfriend’s behavior as I am, because then I’ll know that my reaction is normal and I’m not going insane after all.

Yes, I’m seeking objectivity, but only because I’m convinced that objectivity will rule in my favor.

I hear Caroline clicking away on her keyboard. Tap, tap, tap.

“How about—no, scratch that, he thinks much too highly of himself,” she says of some unnamed therapist. She goes back to her keyboard.

Tap, tap, tap.

“There’s a colleague who used to be in my consultation group,” she begins. “But I’m not sure. He’s great. Very skilled. He always has insightful things to say. It’s just—”

Caroline hesitates.

“Just what?”

“He’s so happy all the time. It feels . . . unnatural. Like, what the hell is he so happy about? But some patients like that. Do you think your friend would do well with him?”

“Definitely not,” I say. I, too, am suspicious of chronically happy people.

Next Caroline names a good therapist I also know relatively well, so I tell her that he won’t work out for my friend because there’s a conflict—therapist shorthand for “Their worlds collide, but I can’t reveal more.”

She clicks around again—tap, tap, tap—then stops.

“Oh, hey, there’s a psychologist named Wendell Bronson,” Caroline says. “I haven’t talked to him in years, but we trained together and he’s smart. Married with kids. Late forties or so, been doing this a long time. Do you want his info?”

I say I do. I mean, “my friend” does. We exchange some pleasantries and then hang up.

At this point, all I know about Wendell is what Caroline has just told me and that there’s two-hour free parking in the lot across the street from his office. I know about the parking because when Caroline texts me his phone number and address a minute after our call, I realize that my bikini-wax place happens to be on the same street (Not that I’ll be needing those services for the foreseeable future, I think, which makes me start crying again).

I pull it together long enough to dial Wendell’s number, and of course I get voicemail. Therapists rarely answer their office phones so that patients won’t feel rebuffed if they call in a crisis and their therapists have only a few minutes between sessions to speak. Colleague-to-colleague calls are made via cell phone or pager.

I hear a generic outgoing recording (“Hi, you’ve reached the office of Wendell Bronson. I return my calls during business hours Monday through Friday. If this is an emergency, please call . . .”), and after the beep I leave a concise message with exactly the information a therapist wants—name, one-liner about why I’m calling, and return phone number. I’m doing well until, thinking it might get me in to see him sooner, I add that I’m also a therapist, but my voice cracks as I say the word therapist. Mortified, I cover with a cough and quickly hang up.

When Wendell calls me back an hour later, I try to sound as together as possible as I explain that I just need a little crisis management, a few weeks to “process” an unexpected breakup, and then I’ll be good to go. I’ve done therapy before, I say, so I come “preshrunk.” He doesn’t laugh at my joke so I’m pretty sure he has no sense of humor, but it doesn’t matter because I don’t need a sense of humor for crisis management.

This is, after all, just about getting me back on my feet.

Wendell says about five words the entire call. I use the term words loosely because it’s more like a bunch of Uh-huhs before he offers a nine o’clock appointment the next morning. I accept and we’re done.

Although Wendell didn’t say much, our conversation provides me with immediate relief. I know this is a common placebo effect: patients often feel hopeful after making that first appointment, before even setting foot in the therapy room. I’m no different. Tomorrow, I think, I’ll get help with this. Yes, I’m a mess now because this whole thing is a shock, but soon I’ll make sense of it (that is, Wendell will confirm that Boyfriend is a sociopath). When I look back, this breakup will be a blip on the radar screen of my life. It will be a mistake that I will have learned from, the kind of mistake my son calls “a beautiful oops.”

That night before I go to sleep, I gather up Boyfriend’s things—his clothes, toiletries, tennis racket, books, and electronics—and pack them in a box that I’ll give back to him. I take the Costco pajamas out of my drawer and find a Post-it with a flirtatious note that Boyfriend had stuck on one of them. When he wrote that, I wonder, did he already know he was leaving?

At a case consultation I went to the week before the breakup, a colleague brought up a patient who found out that her husband had been leading a double life. Not only had he been having an affair for years, but he’d gotten the woman pregnant and she was about to have his baby. When his wife discovered all of this (was he ever going to tell her?), she no longer knew what to make of her life with him. Were her memories real? For example, that romantic vacation—was her version of the trip accurate or was it some fiction, given that he was having his affair at that time? She felt robbed of her marriage but also of her memories. Likewise, when Boyfriend put the Post-it on my pajamas—when he bought me the pajamas in the first place—was he also secretly planning his kid-free life? I frown at the note. Liar, I think.

I walk the box out to the car and place it on the front seat so I’ll remember to drop it off. Maybe I’ll even do it in the morning, on the way to my appointment with Wendell.

I can’t wait for him to tell me what a sociopath Boyfriend is.

The Beginning of Knowing

I’m standing in the doorway of Wendell’s office, trying to figure out where to sit. I see a lot of therapy offices in my profession—my supervisors’ offices during training, my colleagues’ offices that I visit—but I’ve never seen one like Wendell’s.

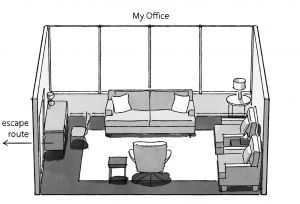

Yes, there are the usual diplomas on the walls and therapy-related books on the shelves, along with the conspicuous absence of anything that might give away his personal life (no family photos on the desk, for instance; just a lone laptop). But instead of the standard setup of the therapist’s chair in the middle of the room with seating against the walls (during internship, we learned to sit close to the door in case “things escalated” and we needed an escape route), Wendell’s office has two long sofas on the far walls arranged in an L-shape with a side table between them—and no therapist chair at all.

I’m flummoxed.

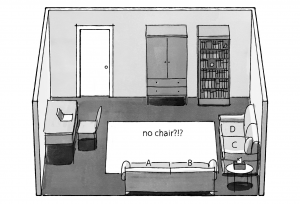

Here’s a diagram of my office:

And here’s a diagram of Wendell’s office.

Wendell, who is very tall and very thin with a balding head and the stooped posture of our profession, stands there waiting for me to take a seat. I consider the possibilities. I assume we won’t sit side by side on the same sofa, but which sofa does he typically take? The one by the window (so he can escape through that if things escalate)? Or the one by the wall? I decide to take a seat by the window, position A, before he closes the door, walks across the room, and relaxes into position C.

Generally when I see a new patient, I’ll open the conversation with an icebreaker like “So, tell me what brings you here today.”

Wendell, however, says nothing. He just looks at me, his green eyes questioning. He’s wearing a cardigan, khakis, and loafers, like he came straight from Therapist Central Casting.

“Hi,” I say.

“Hi,” he replies. And he waits.

About a minute passes, which is longer than it sounds, and I try to gather my wits so that I can clearly lay out the Boyfriend situation. The truth is, every day since the breakup has been worse than the night of the breakup itself because now a glaring void has opened up in my life. For the past couple of years, Boyfriend and I had been in constant contact throughout our days, had said good night every bedtime. Now what was he doing? How had his day gone? Did his presentation at work go well? Was he thinking about me? Or was he glad to have gotten the truth off his chest so he could go search for somebody who was kid-free? I’ve felt his absence in every cell of my body, so by the time I get to Wendell’s office this morning, I’m a wreck—but I don’t want that to be his first impression of me.

Or, to be honest, his second or hundredth.