CHAPTER 72

‘In certain decks of Tarot cards,’ Baillard said eventually, ‘the card representing the Devil is modelled upon the head of Baphomet, the idol the Poor Knights of the Temple of Solomon were accused – falsely – of worshipping.’

Léonie nodded, although it was not clear to her how this digression might be of relevance.

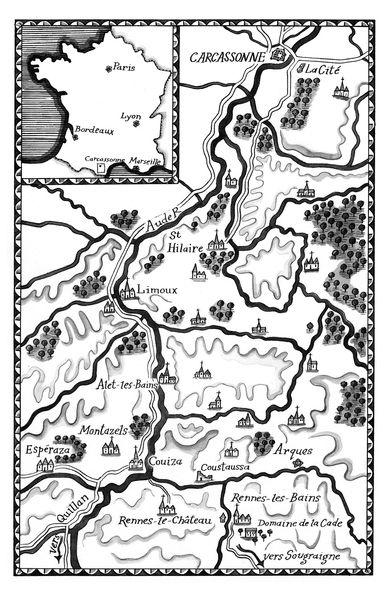

‘There was said to be a Templar presbytery not far from here, at Bézu,’ he continued. ‘No such thing existed, of course. In the matter of historical record, there has been confusion in the collective memory, a conflation of the Albigensians and the Poor Knights. They did bestride the earth contemporaneously, but were little connected one with the other. A coincidence of timing, not an overlapping. ’

‘But how does this connect to the Domaine de la Cade, Monsieur Baillard?’

He smiled. ‘You observed, on your visit, the statue of Asmodeus in the sepulchre, è? Bearing the burden of the bénitier?’

‘I did.’

‘Asmodeus, also known as Ashmadia or Asmodai, is most likely derived from a form of Persian, the phrase aeshmadaeva , meaning demon of wrath. Asmodeus appears in the deuterocanonical Book of Tobit and, again, in the Testament of Solomon, which is a pseudepigraphical work of the Old Testament. That is, a work purportedly written by and attributed to Solomon, but unlikely to have been so in historical truth.’

Léonie nodded, even though her knowledge of the Old Testament was somewhat limited. Neither she nor Anatole had attended Sunday school or learnt their catechism. Religious superstition, their mother claimed, sat ill with modern sensibilities. Traditional in ways of society and manners, Marguerite was a vehement opponent of the Church. Léonie suddenly wondered, for the first time, if the violence of her mother’s feelings could be traced back to the atmosphere of the Domaine de la Cade within which she had endured her childhood, and made a note to ask her at the earliest opportunity.

Monsieur Baillard’s calm voice called her back from her reflections.

‘The story tells of how King Solomon invokes Asmodeus to aid in the construction of the Temple – the great Temple. Asmodeus, a demon most particularly associated with lust, does appear, but his presence is disturbing. He predicts that Solomon’s kingdom will one day be divided.’

Baillard stood up, crossed the room and took from the shelf a small brown leatherbound book. He turned the tissue-thin pages with his delicate fingers until he found the passage he wanted.

‘It reads: “My constellation is like an animal which reclines in its den, spake the demon. So do not ask me so many things, Solomon, for eventually your kingdom will be divided. This glory of yours is temporary. You have us to torture for a little while; then we shall disperse among human beings again with the result that we shall be worshipped as gods because men do not know the name of the angels who rule over us.” ’ He closed the book and looked up. ‘Testament of Solomon, chapter five, verses four and five.’

Léonie did not know how she should react to this, so remained silent.

‘Asmodeus, as I said previously, is a demon associated with carnal desires,’ Baillard continued. ‘He is most especially an enemy of newly weds. In the apocryphal Book of Tobit, he torments a woman called Sarah, killing each of her seven husbands before the marriages can be consummated. On the eighth occasion, the angel Raphaël instructs Sarah’s latest suitor to place the heart and liver of a fish on red-hot cinders. The smoky, foul-smelling vapour repels Asmodeus and causes him to flee to Egypt, where Raphaël binds him, his power broken.’

Léonie shivered, not at his words but at the sudden memory of the faint, but disgusting, stench that had assailed her senses in the sepulchre. An inexplicable scent of damp, smoke and the sea.

‘These parables seem rather archaic, do they not?’ said her host. ‘They are intended to convey some larger truth, but so often serve only to obscure.’ He tapped the leather book with his long, thin fingers. ‘In the Book of Solomon, it is also said that Asmodeus detests being near water.’

Léonie sat up straighter. ‘Hence perhaps the holy water stoup being set upon his shoulders? Could that be, Monsieur Baillard?’

‘It could,’ he agreed. ‘Asmodeus appears in other works of religious commentary. In the Talmud, for example, he corresponds with Ashmedai, a far less malevolent character than the Asmodeus of Tobit, although his desires are focused on Solomon’s wives and Bath-sheba. Some years later, in the middle of the fifteenth century, Asmodai appears as the demon of lust in the Malleus Maleficarum, a rather simplistic catalogue, to my mind, of demons and their ill works. As a collector, it is a book perhaps your brother would know?’

Léonie shrugged. ‘He might well, yes.’

‘There are those who believe that different devils have particular potency at different times of the year.’

‘And when is Asmodeus considered to be at his most powerful?’

‘During the month of November.’

‘November,’ she echoed. She thought a moment. ‘But what does it mean, Monsieur Baillard, this marriage of superstition and supposition – the cards, the sepulchre, such a demon with his fear of water and hatred of marriage?’

He returned the book to the shelf, then walked over to the window and placed his hands upon the sill, with his back to her.

‘Monsieur Baillard?’ she prompted.

He turned round. For a moment, the copper sun coming in through the wide window seemed to cast a halo of light around him. Léonie had the impression that she was looking at an Old Testament prophet such as one might see in an oil painting.

Then he stepped back into the centre of the room, and the illusion was lost.

‘It means, Madomaisèla, that when village superstitions talk of a demon walking these valleys and wooded hillsides, when the times are out of joint, we should not dismiss them as stories only. There are certain places – the Domaine de la Cade is one – where older forces are at work.’ He paused. ‘Alternatively, there are others who choose to raise such a creature, to commune with such spirits, failing to understand that evil cannot be mastered.’

She didn’t believe it, yet at the same time her heart skipped a beat.

‘And my uncle did this, Monsieur Baillard? Are you asking me to accept that my uncle, through the agency of the cards and the spirit of the place, called forth the devil Asmodeus? And then found himself unable to master him? That all those stories of a beast are, in point of fact, true? That my uncle was responsible, morally at least, for the killings in the valley? And knew this?’

Audric Baillard held her gaze. ‘He knew it.’

‘And so that was why he was obliged to seek the services of Abbé Saunière,’ she continued, ‘to banish the monster he had released?’ She stopped. ‘Did Tante Isolde know of this?’

‘It was before her time here. She did not.’

Léonie stood up and walked to the window. ‘I do not believe it,’ she said abruptly. ‘Such stories. Devils, demons. Such tales cannot be credited in the modern world.’ Then her voice dropped, thinking of the pity of it. ‘Those children, ’ she whispered. She resumed her pacing, causing the floorboards to creak and groan in protest. ‘I do not believe it,’ she repeated, but her voice was less certain.

‘Blood will attract blood,’ Baillard said quietly. ‘There are some things that draw evil to them. A place, an object, a person may, by force of their ill will, draw to them ill circumstances, wrongdoings, sins.’

Léonie came to a halt, her thoughts running along other pathways. She looked at her gentle host, then threw herself back into her chair.

‘Even supposing I could accept such things, what of the deck of cards, Monsieur Baillard? Unless I mistake your meaning, you are suggesting that they might be a force for good or for ill, depending on the circumstances of their use.’

‘That is so. Consider how a sword is either an instrument for good or for bad. It is the hand that wields it that makes it so, not the steel.’

Léonie nodded. ‘What is the provenance of the cards? Who painted them in the first instance and for what purpose? When I first read my uncle’s words, I understood him to be saying that the paintings upon the wall of the sepulchre might somehow step down and imprint themselves upon the cards.’

Audric Baillard smiled. ‘If that were the case, Madomaisèla Léonie, there would be only eight cards, whereas there is a full deck.’

Her heart sank. ‘Yes, I suppose so. I had not considered that.’

‘Although,’ he continued, ‘it does not mean that there is not some kernel of truth in what you say.’

‘In which case, Monsieur Baillard, tell me, why those eight tableaux in particular?’ Her green eyes were sparkling as a new idea came to her. ‘Could it be that the images that remain imprinted upon the wall are those very same that my uncle drew to him. That in another situation, another such communication between the worlds, it might be other tableaux, images from other cards, visible upon the walls?’ She paused. ‘From paintings, perhaps?’

Audric Baillard allowed a faint smile to play across his lips. ‘The lesser of the cards, simple playing cards, if you will, date from that unhappy time when, once more, men driven by faith to murder and to oppress and to extirpate heresy plunged the world into blood.’

‘The Albigensians?’ Léonie said, remembering conversations between Anatole and Isolde about the tragic thirteenth-century history of the Languedoc.

He gave a resigned shake of his head. ‘Ah, if only lessons were learnt so quickly, Madomaisèla. But I fear they are not.’

In the gravitas of his voice, it seemed to Léonie that behind his words lay a wisdom that spanned centuries. And she, who had never taken the slightest interest in the events of the past, found herself wishing to understand how one consequence led to another.

‘I speak not of the Albigensians, Madomaisèla Léonie, but instead of the later wars of religion, the conflicts of the sixteenth century between the Catholic house of Guise and what we might call, for sake of clarity, the Huguenot house of Bourbon. ’ He raised his hands, and then let them drop. ‘As always, perhaps it will be ever thus, the demands of faith quickly become inextricably bound to those of territory and control.’

‘And the cards date from this period?’ she urged.

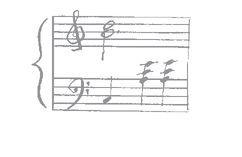

‘The original fifty-six of the cards, intended simply to help pass a long winter’s evening, followed much in the tradition of the Italian game of tarrochi. A hundred years prior to the time of which I speak, the Italian court and nobility had given birth to a fashion for such entertainments. When the Republic was born, the court cards were replaced by Maître and Maîtresse, Fils and Fille, as you have seen.’

‘La Fille d’Épées,’ she said, remembering the painting upon the wall of the sepulchre. ‘By when?’

‘That is not so clear. It was at much the same time, on the eve, indeed, of the Revolution, that in France the harmless game of Tarot was transformed into something other. A system of divination, a way of linking the seen and known to the unseen and unknown.’

‘So the deck of cards was already at the Domaine de la Cade?’

‘The fifty-six cards were the possession of the house, if you like, rather than the individuals within it. The ancient spirit of the place worked upon the deck; the legends and rumours invested the cards with some further meaning and purpose. The cards were waiting, you see, for one who would complete the sequence.’

‘My uncle,’ she said, a statement, not a question.

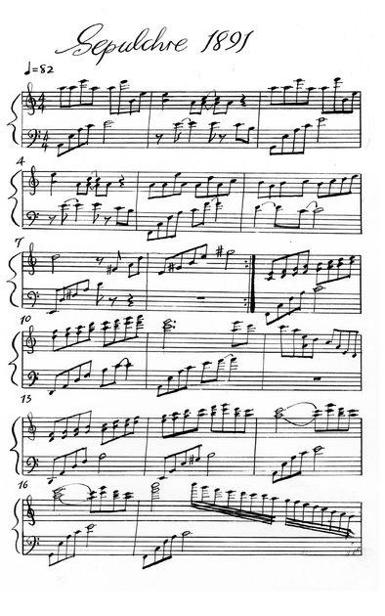

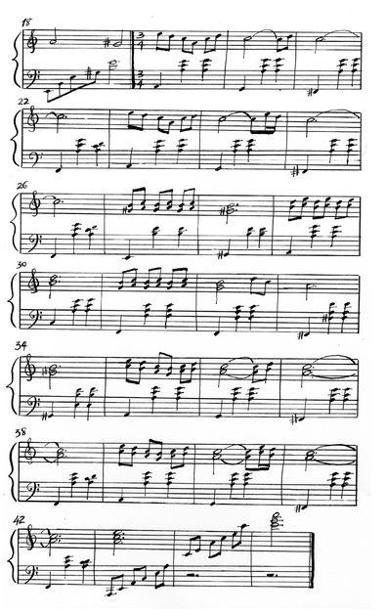

Baillard nodded. ‘Lascombe read the books being published by the cartomancers in Paris – the antique words of Antoine Court de Gébelin, the contemporary writings of Eliphas Lévi and Romain Merlin – and was seduced by them. To the deck of cards he had inherited he added the twenty-two greater arcana – those speaking of the fundamental turns of life and what lies beyond – and fixed those he wished to summon to him upon the wall of the sepulchre. ’

‘My late uncle painted the twenty-two additional cards?’

‘He did.’ He paused. ‘You believe absolutely, then, Madomaisèla Léonie, that through the agency of the Tarot cards – in the specific place and with the conditions that make such things possible – demons, ghosts might be summoned? ’

‘It does not credit belief, Monsieur Baillard yet I find I do believe it.’ She paused and thought for a moment. ‘What I do not understand, however, is how the cards control the spirits.’

‘Ah, no,’ Baillard said swiftly. ‘That was the mistake your uncle made. The cards may summon the spirits, yes, but never control them. All possibilities are contained within the images – all character, all human desire, good and ill, all of our long and overlapping stories – but should they be released, they take on a life of their own.’

Léonie frowned. ‘I don’t understand.’

‘The tableaux upon the wall are the imprints of the last cards summoned in that place. But if one were to alter, through the touch of a brush, the features on one or other of the cards, they would take on other characteristics instead. The cards can tell different stories,’ he said.

‘Would this be true of these cards anywhere?’ she asked. ‘Or only in the Domaine de la Cade, in the sepulchre?’

‘It is the unique combination, Madomaisèla, of image and sound and the spirit of the place. That one place,’ he replied. ‘At the same time, the place works upon the cards. So, for example, it might be that La Force, now, attaches itself specifically to you. Through your artistry.’

Léonie looked at him. ‘But I have not seen the cards themselves. Indeed, I have not painted cards, only imitations on common paper of what I saw on the walls.’

He gave a slow smile. ‘Things do not always hold fast, Madomaisèla. And besides, you have painted more than yourself into the cards, have you not? You have painted your brother and your aunt into these pictures also.’

She blushed. ‘They are just paintings intended as a memento of our time spent here.’

‘Perhaps.’ He inclined his head to one side. ‘Through such pictures your stories will endure longer than you have tongue to tell them.’

‘You are frightening me, Monsieur,’ she said sharply.

‘That is not my intention.’

Léonie paused before asking the question that had been on her lips since the very first moment she heard of the Tarot cards. ‘Does the deck exist still?’

He fixed her with his wise eyes. ‘The deck survives,’ he said finally.

‘Within the house?’ she asked quickly.

‘The Abbé Saunière begged your uncle to destroy the cards, to burn them, so that no other man would be tempted to make use of them. The sepulchre too.’ Baillard shook his head. ‘But Jules Lascombe was a scholar. He could no more destroy something of such ancient origin than the Abbé himself could denounce his God.’

‘Are the cards hidden within the grounds, then? I am certain they are not in the sepulchre.’

‘They are safe,’ he said. ‘Concealed where the river runs dry, in a place where once the ancient kings were buried.’

‘But if that is the case, then—’

Audric Baillard raised his finger to his lips. ‘I have told you all this as a way to curb your inquisitive nature, Madomaisèla Léonie, not to fan your curiosity. I understand how you have been drawn into this story, how you wish to have some more explicit understanding of your family and the events that have shaped their lives. But I repeat my warning: no good will come of trying to find the cards, especially at such a time, when matters hang so delicately balanced.’

‘At such a time? What do you mean, Monsieur Baillard? Because November approaches?’

But it was clear from the expression that had fallen over his face that he was prepared to say nothing further. Léonie tapped her foot. She had so many questions she wished to ask. She drew breath, but he spoke before she could say more.

‘It is enough,’ he said.

Through the open window came the sound of the bell of the tiny church of Saint-Celse and Saint-Nazaire tolling out the midday. An emaciated single note marking the passing of the morning.

The sound jerked Léonie’s attention back into the present. She had quite forgotten her task. She leapt to her feet.

‘Forgive me, Monsieur Baillard, I have taken up more than enough of your time.’ She dragged her gloves on over her fingers. ‘And in so doing have quite forgotten my own responsibilities this morning. The bureau de poste . . . If I hurry, I might still …’

Clutching her hat, Léonie ran across the room to the door. Audric Baillard drew himself to his feet, an elegant and timeless figure.

‘If I may, Monsieur, I will call again? Au revoir.’

‘Of course, Madomaisèla. The pleasure will be mine.’ Léonie waved, then quitted the room, rushing down the passageway and out of the front door into the street, leaving Audric Baillard alone in the quiet room deep in reflection. The boy slipped out of the shadows and closed the door behind her.

Baillard sat down once more in his chair.

‘Si es atal es atal,’ he muttered, in the old language. Things will be as they will be. ‘But with this child, I wish it were not so.’