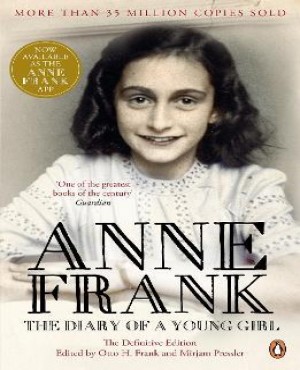

In 1942, with the Nazis occupying Holland, a thirteen-year-old Jewish girl and her family fled their home in Amsterdam and went into hiding. For the next two years, until their whereabouts were betrayed to the Gestapo, the Franks and another family lived cloistered in the “Secret Annexe” of an old office building. Cut off from the outside world, they faced hunger, boredom, the constant cruelties of living in confined quarters, and the ever-present threat of discovery and death. In her diary Anne Frank recorded vivid impressions of her experiences during this period. By turns thoughtful, moving, and surprisingly humorous, her account offers a fascinating commentary on human courage and frailty and a compelling self-portrait of a sensitive and spirited young woman whose promise was tragically cut short.

BOOK FLAP

Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl is among the most enduring

documents of the twentieth century. Since its publication in 1947, it has been

read by tens of millions of people all over the world. It remains a beloved and

deeply admired testament to the indestructable nature of the human spirit.

Restore in this Definitive Edition are diary entries that had been omitted from

the original edition. These passages, which constitute 30 percent more

material, reinforce the fact that Anne was first and foremost a teenage girl,

not a remote and flawless symbol. She fretted about, and tried to copie with,

her own emerging sexuality. Like many young girls, she often found herself

in disagreement with her mother. And like any teenager, she veered between

the carefree nature of a child and the full-fledged sorrow of an adult. Anne

emerges more human, more vulnerable, and more vital than ever.

Anne Frank and her family, fleeing the horrors of Nazi occupation, hid in the

back of an Amsterdam warehouse for two years. She was thirteen when the

family went into the Secret Annex, and in these pages she grows to be a

young woman and a wise observer of human nature as well. With unusual

insight, she reveals the relations between eight people living under

extraordinary conditions, facing hunger, the ever-present threat of discovery

and death, complete estrangement from the outside world, and above all, the

boredom, the petty misunderstandings, and the frustrations of living under

such unbearable strain, in such confined quarters.

A timely story rediscovered by each new generation, The Diary of a Young

Girl stands without peer. For both young readers and adults it continues to

bring to life this young woman, who for a time survived the worst horror of

the modern world had seen — and who remained triumphantly and

heartbreakingly human throughout her ordeal. For those who know and love

Anne Frank, The Definitive Edition is a chance to discover her anew. For

readers who have not yet encountered her, this is the edition to cherish.

ANNE FRANK was born on June 12, 1929. She died while imprisoned at

Bergen-Belsen, three months short of her sixteenth birthday. OTTO H.

FRANK was the only member of his immediate framily to survive the

Holocaust. He died in 1980.

MIRJAM PRESSLER is a popular writer of books for young adults. She lives

in Germany.

Translated by Susan Massotty.

FOREWORD

Anne Frank kept a diary from June 12, 1942, to August 1, 1944. Initially, she

wrote it strictly for herself. Then, one day in 1944, Gerrit Bolkestein, a

member of the Dutch government in exile, announced in a radio broadcast

from London that after the war he hoped to collect eyewitness accounts of the

suffering of the Dutch people under the German occupation, which could be

made available to the public. As an example, he specifically mentioned letters

and diaries.

Impressed by this speech, Anne Frank decided that when the war was over

she would publish a book based on her diary. She began rewriting and editing

her diary, improving on the text, omitting passages she didn’t think were

interesting enough and adding others from memory. At the same time, she

kept up her original diary. In the scholarly work The Diary of Anne Frank:

The Critical Edition (1989), Anne’s first, unedited diary is referred to as

version a, to distinguish it from her second, edited diary, which is known as

version b.

The last entry in Anne’s diary is dated August 1, 1944. On August 4, 1944,

the eight people hiding in the Secret Annex were arrested. Miep Gies and

Bep Voskuijl, the two secretaries working in the building, found Anne’s

diaries strewn allover the floor. ,Miep Gies tucked them away in a desk

drawer for safekeeping. After the war, when it became clear that Anne was

dead, she gave the diaries, unread, to Anne’s father, Otto Frank.

After long deliberation, Otto Frank decided to fulfill his daughter’s wish and

publish her diary. He selected material from versions a and b, editing them

into a shorter version later referred to as version c. Readers all over the world

know this as The Diary of a fauna Girl.

In making his choice, Otto Frank had to bear several points in mind. To begin

with, the book had to be kept short so that it would fit in with a series put out

by the Dutch publisher. In addition, several passages dealing with Anne’s

sexuality were omitted; at the time of the diary’s initial publication, in 1947, it

was not customary to write openly about sex, and certainly not in books for

young adults. Out of respect for the dead, Otto Frank also omitted a number

of unflattering passages about his wife and the other residents of the Secret

Annex. Anne Frank, who was thirteen when she began her diary and fifteen

when she was forced to stop, wrote without reserve about her likes and

dislikes.

When Otto Frank died in 1980, he willed his daughter’s manuscripts to the

Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation in Amsterdam. Because

the authenticity of the diary had been challenged ever since its publication,

the Institute for War Documentation ordered a thorough investigation. Once

the diary was proved, beyond a shadow of a doubt, to be genuine, it was

published in its entirety, along with the results of an exhaustive study. The

Critical Edition contains not only versions a, band c, but also articles on the

background of the Frank family, the circumstances surrounding their arrest

and deportation, and the examination into Anne’s handwriting, the document

and the materials used.

The Anne Frank-Fonds (Anne Frank Foundation) in Basel (Switzerland),.

which as Otto Frank’s sole heir had also inherited his daughter’s copyrights,

then decided to have anew, expanded edition of the diary published for

general readers. This new edition in no way affects the integrity of the old

one originally edited by Otto Frank, which brought the diary and its message

to millions of people. The task of compthng the expanded edition was given

to the writer and translator Mirjam Pressler. Otto Frank’s original selection

has now been supplemented with passages from Anne’s a and b versions.

Mirjam Pressler’s definitive edition, approved by the Anne Frank-Fonds,

contains approximately 30 percent more material and is intended to give the

reader more insight into the world of Anne Frank.

In writing her second version (b), Anne invented pseudonyms for the people

who would appear in her book. She initially wanted to call herself Anne

Aulis, and later Anne Robin. Otto Frank opted to call his family by their own

names and to follow Anne’s wishes with regard to the others. Over the years,

the identity of the people who helped the family in the Secret Annex has

become common knowledge. In this edition, the helpers are now referred to

by their real names, as they so justly deserve to be. All other persons are

named in accordance with the pseudonyms in The Critical Edition.

The Institute for War Documentation has arbitrarily assigned initials to those

persons wishing to remain anonymous.

The real names of the other people hiding in the Secret Annex are:

THE VAN PELS FAMILY

(from Osnabriick, Germany):

Auguste van Pels (born September 9, 1890)

Hermann van Pels (born March 31, 1889)

Peter van Pels (born November 8, 1926)

Called by Anne, in her manuscript: Petronella, Hans and Alfred van Daan;

and in the book: Petronella, Hermann and Peter van Daan.

FRITZ PFEFFER

(born April 30, 1889, in Giessen, Germany): Called by Anne, in her

manuscript and in the book: Alfred Dussel.

The reader may wish to bear in mind that much of this edition is based on the

b version of Anne’s diary, which she wrote when she was around fifteen years

old. Occasionally, Anne went back and commented on a passage she had

written earlier. These comments are clearly marked in this edition.

Naturally, Anne’s spelling and linguistic errors have been corrected.

Otherwise, the text has basically been left as she wrote it, since any attempts

at editing and clarification would be inappropriate in a historical document.

— : —

I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been able

to confide in anyone, and I hope you will be a great source of comfort and

support.

June 12, 1942I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been ableto confide in anyone, and I hope you will be a great source of comfort andsupport.COMMENT ADDED BY ANNE ON SEPTEMBER 28, 1942: So far youtruly have been a areat source of comfort to me, and so has Kitty, whom Inow write to regularly. This way of keeping a diary is much nicer, and now Ican hardly wait for those moments when I’m able to write in you. Oh, I’m soalad I brought you along!SUNDAY, JUNE 14, 1942I’ll begin from the moment I got you, the moment I saw you lying on the tableamong my other birthday presents. (I went along when you were bought, butthat doesn’t count.) On Friday, June 12, I was awake at six o’clock, whichisn’t surprising, since it was my birthday. But I’m not allowed to get up at thathour, so I had to control my curiosity until quarter to seven. When I couldn’twait any longer, I went to the dining room, where Moortje (the cat)welcomed me by rubbing against my legs.A little after seven I went to Daddy and Mama and then to the living room toopen my presents, and you were the first thing I saw, maybe one of my nicestpresents. Then a bouquet of roses, some peonies and a potted plant. FromDaddy and Mama I got a blue blouse, a game, a bottle of grape juice, whichto my mind tastes a bit like wine (after all, wine is made from grapes), apuzzle, a jar of cold cream, 2.50guilders and a gift certificate for two books. I got another book as well,Camera Obscura (but Margot already has it, so I exchanged mine forsomething else), a platter of homemade cookies (which I made myself, ofcourse, since I’ve become quite an expert at baking cookies), lots of candyand a strawberry tart from Mother. And a letter from Grammy, right on time,but of course that was just a coincidence.Then Hanneli came to pick me up, and we went to school.During recess I passed out cookies to my teachers and my class, and then itwas time to get back to work. I didn’t arrive home until five, since I went togym with the rest of the class. (I’m not allowed to take part because myshoulders and hips tend to get dislocated.) As it was my birthday, I got todecide which game my classmates would play, and I chose volleyball.Afterward they all danced around me in a circle and sang “Happy Birthday.”When I got home, Sanne Ledermann was already there. Ilse Wagner, HanneliGoslar and Jacqueline van Maarsen came home with me after gym, sincewe’re in the same class. Hanneli and Sanne used to be my two best friends.People who saw us together used to say, “There goes Anne, Hanne andSanne.” I only met Jacqueline van Maarsen when I started at the JewishLyceum, and now she’s my best friend. Ilse is Hanneli’s best friend, andSanne goes to another school and has friends there.They gave me a beautiful book, Dutch Sasas and Lesends, but they gave meVolume II by mistake, so I exchanged two other books for Volume I. AuntHelene brought me a puzzle, Aunt Stephanie a darling brooch and Aunt Lenya terrific book: Daisy Goes to the Mountains.This morning I lay in the bathtub thinking how wonderful it would be if I hada dog like Rin Tin Tin. I’d call him Rin Tin Tin too, and I’d take him toschool with me, where he could stay in the janitor’s room or by the bicycleracks when the weather was good.MONDAY, JUNE 15, 1942I had my birthday party on Sunday afternoon. The Rin Tin Tin movie was abig hit with my classmates. I got two brooches, a bookmark and two books.I’ll start by saying a few things about my school and my class, beginning withthe students.Betty Bloemendaal looks kind of poor, and I think she probably is. She liveson some obscure street in West Amsterdam, and none of us know where it is.She does very well at school, but that’s because she works so hard, notbecause she’s so smart. She’s pretty quiet.Jacqueline van Maarsen is supposedly my best friend, but I’ve never had areal friend. At first I thought Jacque would be one, but I was badly mistaken.D.Q.* * Initials have been assigned at random to those persons who prefer toremain anonymous. is a very nervous girl who’s always forgetting things, sothe teachers keep assigning her extra homework as punishment. She’s verykind, especially to G.Z.E.S. talks so much it isn’t funny. She’s always touching your hair or fiddlingwith your buttons when she asks you something. They say she can’t stand me,but I don’t care, since I don’t like her much either.Henny Mets is a nice girl with a cheerful disposition, except that she talks ina loud voice and is really childish when we’re playing outdoors.Unfortunately, Henny has a girlfriend named Beppy who’s a bad influence onher because she’s dirty and vulgar.J.R. – I could write a whole book about her. J. is a detestable, sneaky, stuckup, two-faced gossip who thinks she’s so grown-up. She’s really got Jacqueunder her spell, and that’s a shame. J. is easily offended, bursts into tears atthe slightest thing and, to top it all off, is a terrible show-off. Miss J. alwayshas to be right. She’s very rich, and has a closet full of the most adorabledresses that are way too old for her. She thinks she’s gorgeous, but she’s not.J. and I can’t stand each other.Ilse Wagner is a nice girl with a cheerful disposition, but she’s extremelyfInicky and can spend hours moaning and groaning about something. Ilselikes me a lot. She’s very smart, but lazy.Hanneli Goslar, or Lies as she’s called at school, is a bit on the strange side.She’s usually shy — outspoken at horne, but reserved around other people.She blabs whatever you tell her to her mother. But she says what she thinks,and lately I’ve corne to appreciate her a great deal.Nannie van Praag-Sigaar is small, funny and sensible. I think she’s nice. She’spretty smart. There isn’t much else you can say about Nannie. Eefje de Jongis, in my opinion, terrific. Though she’s only twelve, she’s quite the lady. Sheacts as if I were a baby. She’s also very helpful, and I like her.G.Z. is the prettiest girl in our class. She has a nice face, but is kind of dumb.I think they’re going to hold her back a year, but of course I haven’t told herthat.COMMENT ADDED BY ANNE AT A LATER DATE: To my areatsurprise, G.Z. wasn’t held back a year after all.And sitting next to G.Z. is the last of us twelve girls, me.There’s a lot to be said about the boys, or maybe not so much after all.Maurice Coster is one of my many admirers, but pretty much of a pest. SallieSpringer has a filthy mind, and rumor has it that he’s gone all the way. Still, Ithink he’s terrific, because he’s very funny.Emiel Bonewit is G.Z.’s admirer, but she doesn’t care.He’s pretty boring. Rob Cohen used to be in love with me too, but I can’tstand him anymore. He’s an obnoxious, two-faced, lying, sniveling little goofwho has an awfully high opinion of himself.Max van de Velde is a farm boy from Medemblik, but eminently suitable, asMargot would say.Herman Koopman also has a filthy mind, just like Jopie de Beer, who’s aterrible flirt and absolutely girl-crazy.Leo Blom is Jopie de Beer’s best friend, but has been ruined by his dirtymind.Albert de Mesquita came from the Montessori School and skipped a grade.He’s really smart.Leo Slager came from the same school, but isn’t as smart.Ru Stoppelmon is a short, goofy boy from Almelo who transferred to thisschool in the middle of the year.C.N. does whatever he’s not supposed to.Jacques Kocernoot sits behind us, next to C., and we (G.and I) laugh ourselves silly.Harry Schaap is the most decent boy in our class. He’s nice.Werner Joseph is nice too, but all the changes taking place lately have madehim too quiet, so he seems boring. Sam Salomon is one of those tough guysfrom across the tracks. A real brat. (Admirer!)Appie Riem is pretty Orthodox, but a brat too.SATURDAY, JUNE 20,1942Writing in a diary is a really strange experience for someone like me. Notonly because I’ve never written anything before, but also because it seems tome that later on neither I nor anyone else will be interested in the musings ofa thirteen-year-old schoolgirl. Oh well, it doesn’t matter. I feel like writing,and I have an even greater need to get all kinds of things off my chest.”Paper has more patience than people.” I thought of this saying on one ofthose days when I was feeling a little depressed and was sitting at home withmy chin in my hands, bored and listless, wondering whether to stay in or goout. I finally stayed where I was, brooding. Yes, paper does have morepatience, and since I’m not planning to let anyone else read this stiff-backednotebook grandly referred to as a”diary,” unless I should ever find a real friend, it probably won’t make a bit ofdifference.Now I’m back to the point that prompted me to keep a diary in the first place:I don’t have a friend.Let me put it more clearly, since no one will believe that a thirteen year-oldgirl is completely alone in the world.And I’m not. I have loving parents and a sixteen-year-old sister, and there areabout thirty people I can call friends.I have a throng of admirers who can’t keep their adoring eyes off me and whosometimes have to resort to using a broken pocket mirror to try and catch aglimpse of me in the classroom. I have a family, loving aunts and a goodhome. No, on the surface I seem to have everything, except my one truefriend. All I think about when I’m with friends is having a good time. I can’tbring myself to talk about anything but ordinary everyday things. We don’tseem to be able to get any closer, and that’s the problem. Maybe it’s my faultthat we don’t confide in each other. In any case, that’s just how things are, andunfortunately they’re not liable to change.This is why I’ve started the diary.To enhance the image of this long-awaited friend in my imagination, I don’twant to jot down the facts in this diary the way most people would do, but Iwant the diary to be my friend, and I’m going to call this friend Kitty.Since no one would understand a word of my stories to Kitty if I were toplunge right in, I’d better provide a brief sketch of my life, much as I dislikedoing so.My father, the most adorable father I’ve ever seen, didn’t marry my motheruntil he was thirty-six and she was twenty-five. My sister Margot was born inFrankfurt am Main in Germany in 1926. I was born on June 12, 1929. I livedin Frankfurt until I was four. Because we’re Jewish, my father immigrated toHolland in 1933, when he became the Managing Director of the DutchOpekta Company, which manufactures products used in making jam. Mymother, Edith Hollander Frank, went with him to Holland in September,while Margot and I were sent to Aachen to stay with our grandmother.

Margot went to Holland in December, and I followed in February, when Iwas plunked down on the table as a birthday present for Margot.I started right away at the Montessori nursery school. I stayed there until Iwas six, at which time I started first grade. In sixth grade my teacher wasMrs. Kuperus, the principal. At the end of the year we were both in tears aswe said a heartbreaking farewell, because Id been accepted at the JewishLyceum, where Margot also went to school.Our lives were not without anxiety, since our relatives in Germany weresuffering under Hitlers anti-Jewish laws. After the pogroms in 1938 my twouncles (my mothers brothers) fled Germany, finding safe refuge in NorthAmerica. My elderly grandmother came to live with us. She was seventythree years old at the time.After May 1940 the good times were few and far between: first there was thewar, then the capitulation and then the arrival of the Germans, which is whenthe trouble started for the Jews. Our freedom was severely restricted by aseries of anti-Jewish decrees: Jews were required to wear a yellow star; Jewswere required to turn in their bicycles; Jews were forbidden to use street-cars;Jews were forbidden to ride in cars, even their own; Jews were required to dotheir shopping between 3 and 5 P.M.; Jews were required to frequent onlyJewish-owned barbershops and beauty parlors; Jews were forbidden to be outon the streets between 8 P.M. and 6 A.M.; Jews were forbidden to attendtheaters, movies or any other forms of entertainment; Jews were forbidden touse swimming pools, tennis courts, hockey fields or any other athletic fields;Jews were forbidden to go rowing; Jews were forbidden to take part in anyathletic activity in public; Jews were forbidden to sit in their gardens or thoseof their friends after 8 P.M.; Jews were forbidden to visit Christians in theirhomes; Jews were required to attend Jewish schools, etc. You couldnt do thisand you couldnt do that, but life went on. Jacque always said to me, I dontdare do anything anymore, cause Im afraid its not allowed.In the summer of 1941 Grandma got sick and had to have an operation, so mybirthday passed with little celebration. In the summer of 1940 we didnt domuch for my birthday either, since the fighting had just ended in Holland.Grandma died in January 1942. No one knows how often I think of her andstill love her. This birthday celebration in 1942 was intended to make up forthe others, and Grandmas candle was lit along with the rest.The four of us are still doing well, and that brings me to the present date ofJune 20, 1942, and the solemn dedication of my diary.SATURDAY, JUNE 20, 1942Dearest Kitty! Let me get started right away; its nice and quiet now. Fatherand Mother are out and Margot has gone to play Ping-Pong with some otheryoung people at her friend Treess. Ive been playing a lot of Ping-Pongmyself lately.So much that five of us girls have formed a club. Its calledThe Little Dipper Minus Two. A really silly name, but its based on amistake. We wanted to give our club a special name; and because there werefive of us, we came up with the idea of the Little Dipper. We thought itconsisted of five stars, but we turned out to be wrong. It has seven, like theBig Dipper, which explains the Minus Two. Ilse Wagner has a Ping-Pongset, and the Wagners let us play in their big dining room whenever we want.Since we five Ping-Pong players like ice cream, especially in the summer,and since you get hot playing Ping-Pong, our games usually end with a visitto the nearest ice-cream parlor that allows Jews: either Oasis or Delphi.Weve long since stopped hunting around for our purses or money — most ofthe time its so busy in Oasis that we manage to find a few generous youngmen of our acquaintance or an admirer to offer us more ice cream than wecould eat in a week.Youre probably a little surprised to hear me talking about admirers at such atender age. Unfortunately, or not, as the case may be, this vice seems to berampant at our school. As soon as a boy asks if he can bicycle home with meand we get to talking, nine times out of ten I can be sure hell becomeenamored on the spot and wont let me out of his sight for a second. His ardoreventually cools, especially since I ignore his passionate glances and pedalblithely on my way. If it gets so bad that they start rambling on aboutasking Fathers permission, I swerve slightly on my bike, my schoolbagfalls, and the young man feels obliged to get off his bike and hand me thebag, by which time Ive switched the conversation to another topic. These arethe most innocent types. Of course, there are those who blow you kisses ortry to take hold of your arm, but theyre definitely knocking on the wrongdoor. I get off my bike and either refuse to make further use of their companyor act as if Im insulted and tell them in no uncertain terms to go on homewithout me. There you are. Weve now laid the basis for our friendship. Untiltomorrow.Yours, AnneSUNDAY, JUNE 21, 1942Dearest Kitty,Our entire class is quaking in its boots. The reason, of course, is theupcoming meeting in which the teachers decide wholl be promoted to thenext grade and wholl be kept back.Half the class is making bets. G.Z. and I laugh ourselves sick at the two boysbehind us, C.N. and Jacques Kocernoot, who have staked their entire vacationsavings on their bet.From morning to night, its Youre going to pass, No, Im not, Yes, youare, No, Im not. Even G.s pleading glances and my angry outbursts cantcalm them down. If you ask me, there are so many dummies that about aquarter of the class should be kept back, but teachers are the mostunpredictable creatures on earth. Maybe this time theyll be unpredictable inthe right direction for a change. Im not so worried about my girlfriends andmyself.Well make it. The only subject Im not sure about is math. Anyway, all wecan do is wait. Until then, we keep telling each other not to lose heart.I get along pretty well with all my teachers. There are nine of them, sevenmen and two women. Mr. Keesing, the old fogey who teaches math, was madat me for the longest time because I talked so much. After several warnings,he assigned me extra homework. An essay on the subject A Chatterbox. Achatterbox, what can you write about that? Id wbrry about that later, Idecided. I jotted down the assignment in my notebook, tucked it in my bagand tried to keep quiet.That evening, after Id finished the rest of my homework, the note about theessay caught my eye. I began thinking about the subject while chewing thetip of my fountain pen.Anyone could ramble on and leave big spaces between the words, but thetrick was to come up with convincing arguments to prove the necessity oftalking. I thought and thought, and suddenly I had an idea. I wrote the threepages Mr. Keesing had assigned me and was satisfied. I argued that talking isa female trait and that I would do my best to keep it under control, but that Iwould never be able to break myself of the habit, since my mother talked asmuch as I did, if not more, and that theres not much you can do aboutinherited traits.Mr. Keesing had a good laugh at my arguments, but when I proceeded to talkmy way through the next class, he assigned me a second essay. This time itwas supposed to be on An Incorrigible Chatterbox. I handed it in, and Mr.Keesing had nothing to complain about for two whole classes. However,during the third class hed finally had enough. Anne Frank, as punishmentfor talking in class, write an essay entitledQuack, Quack, Quack, said Mistress Chatterback.The class roared. I had to laugh too, though Id ) nearly exhausted myingenuity on the topic of chatterboxes. It was time to come up withsomething else, j something original. My friend Sanne, whos good at poetry,offered to help me write the essay from beginning to end in verse. I jumpedfor joy.Keesing was trying to play a joke on me with this ridiculous subject, but Idmake sure the joke was on him. I finished my poem, and it was beautiful! Itwas about a mother duck and a father swan with three baby ducklings whowere bitten to death by the father because they quacked too much. Luckily,Keesing took the joke the right way. He read the poem to the class, adding hisown comments, and to several other classes as well. Since then Ive beenallowed to talk and havent been assigned any extra homework. On thecontrary, Keesings always i making jokes these days.Yours, AnneWEDNESDAY, JUNE 24, 1942Dearest Kitty,Its sweltering. Everyone is huffing and puffing, and in this heat I have towalk everywhere. Only now do I realize how pleasant a streetcar is, but weJews are no longer allowed to make use of this luxury; our own two feet aregood enough for us. Yesterday at lunchtime I had an appointment with thedentist on Jan Luykenstraat. Its a long way from our school onStadstimmertuinen. That afternoon I nearly fell asleep at my desk.Fortunately, people automatically offer you something to drink. The dentalassistant is really kind.The only mode of transportation left to us is the ferry.The ferryman at Josef Israelkade took us across when we asked him to. Itsnot the fault of the Dutch that we Jews are having such a bad time.I wish I didnt have to go to school. My bike was stolen during Eastervacation, and Father gave Mothers bike to some Christian friends forsafekeeping. Thank goodness summer vacation is almost here; one moreweek and our torment will be over.Something unexpected happened yesterday morning. As I was passing thebicycle racks, I heard my name being called. I turned around and there wasthe nice boy Id met the evening before at my friend Wilmas. Hes Wilmassecond cousin. I used to think Wilma was nice, which she is, but all she evertalks about is boys, and that gets to be a bore. He came toward me, somewhatshyly, and introduced himself as Hello Silberberg. I was a little surprised andwasnt sure what he wanted, but it didnt take me long to find out. He asked ifI would allow him to accompany me to school. As long as youre headedthat way, Ill go with you, I said. And so we walked together. Hello issixteen and good at telling all kinds of funny stories.

He was waiting for me again this morning, and I expect he will be from now

on.

Anne

WEDNESDAY, JULY 1, 1942

Dearest Kitty,

Until today I honestly couldn’t find the time to write you. I was with friends

all day Thursday, we had company on Friday, and that’s how it went until

today.

Hello and I have gotten to know each other very well this past week, and he’s

told me a lot about his life. He comes from Gelsenkirchen and is living with

his grandparents. His parents are in Belgium, but there’s no way he can get

there.

Hello used to have a girlfriend named Ursula. I know her too.

She’s perfectly sweet and perfectly boring. Ever since he met me, Hello has

realized that he’s been falling asleep at Ursul’s side. So I’m kind of a pep

tonic. You never know what you’re good for!

Jacque spent Saturday night here. Sunday afternoon she was at Hanneli’s, and

I was bored stiff.

Hello was supposed to come over that evening, but he called around six. I

answered the phone, and he said, “This is Helmuth Silberberg. May I please

speak to Anne?”

“Oh, Hello. This is Anne.”

“Oh, hi, Anne. How are you?” ”

“Fine, thanks.”

“I just wanted to say I’m sorry but I can’t come tonight, though I would like to

have a word with you. Is it all right if I come by and pick you up in about ten

minutes

“Yes, that’s fine. Bye-bye!”

“Okay, I’ll be right over. Bye-bye!”

I hung up, quickly changed my clothes and fixed my hair. I was so nervous I

leaned out the window to watch for him. He finally showed up. Miracle of

miracles, I didn’t rush down the stairs, but waited quietly until he rang the

bell. I went down to open the door, and he got right to the point.

“Anne, my grandmother thinks you’re too young for me to be seeing you on a

regular basis. She says I should be going to the Lowenbachs’, but you

probably know that I’m not going out with Ursul anymore.”

“No, I didn’t know. What happened? Did you two have a fight?”

“No, nothing like that. I told Ursul that we weren’t suited to each other and so

it was better for us not to go together anymore, but that she was welcome at

my house and I hoped I would be welcome at hers. Actually, I thought Ursul

was hanging around with another boy, and I treated her as if she were. But

that wasn’t true. And then my uncle said I should apologize to her, but of

course I didn’t feel like it, and that’s why I broke up with her. But that was

just one of the reasons.

“Now my grandmother wants me to see Ursul and not you, but I don’t agree

and I’m not going to. Sometimes old people have really old-fashioned ideas,

but that doesn’t mean I have to go along with them. I need my grandparents,

but in a certain sense they need me too. From now on I’ll be free on

Wednesday evenings. You see, my grandparents made me sign up for a

wood-carving class, but actually I go to a club organized by the Zionists. My

grandparents don’t want me to go, because they’re anti-Zionists. I’m not a

fanatic Zionist, but it interests me. Anyway, it’s been such a mess lately that

I’m planning to quit. So next Wednesday will be my last meeting.

That means I can see you Wednesday evening, Saturday afternoon, Saturday

evening, Sunday afternoon and maybe even more.”

“But if your grandparents don’t want you to, you?

shouldn’t go behind their backs.”

“All’s fair in love and war.”

Just then we passed Blankevoort’s Bookstore and there was Peter Schiff with

two other boys; it was the first time he’d said hello to me in ages, and it really

made me feel good.

Monday evening Hello came over to meet Father and Mother.

I had bought a cake and some candy, and we had tea and cookies, the works,

but neither Hello nor I felt like sitting stiffly on our chairs. So we went out

for a walk, and he didn’t deliver me to my door until ten past eight. Father

was furious. He said it was very wrong of me not to get home on time. I had

to promise to be home by ten to eight in the future. I’ve been asked to Hello’s

on Saturday.

Wilma told me that one night when Hello was at her house, she asked him,

“Who do you like best, Ursul or Anne?”

He said, “It’s none of your business.”

But as he was leaving (they hadn’t talked to each other the rest of the

evening), he said, “Well, I like Anne better, but don’t tell anyone. Bye!” And

whoosh. . . he was out the door.

In everything he says or does, I can see that Hello is in love with me, and it’s

kind of nice for a change. Margot would say that Hello is eminently suitable.

I think so too, but he’s more than that. Mother is also full of praise: “A goodlooking boy. Nice and polite.” I’m glad he’s so popular with everyone. Except

with my girlfriends. He thinks they’re very childish, and he’s right about that.

Jacque still teases me about him, but I’m not in love with him. Not really. It’s

all right for me to have boys as friends. Nobody minds.

Mother is always asking me who I’m going to marry when I grow up, but I

bet she’ll never guess it’s Peter, because I talked her out of that idea myself,

without batting an eyelash. I love Peter as I’ve never loved anyone, and I tell

myself he’s only going around with all those other girls to hide his feelings

for me. Maybe he thinks Hello and I are in love with each other, which we’re

not. He’s just a friend, or as Mother puts it, a beau.

Yours, Anne

SUNDAY, JULY 5, 1942

Dear Kitty,

The graduation ceremony in the Jewish Theater on Friday went as expected.

My report card wasn’t too bad. I got one D, a C- in algebra and all the rest

B’s, except for two B+’s and two B-‘s. My parents are pleased, but they’re not

like other parents when it comes to grades. They never worry about report

cards, good or bad. As long as I’m healthy and happy and don’t talk back too

much, they’re satisfied. If these three things are all right, everything else will

take care of itself.

I’m just the opposite. I don’t want to be a poor student.

I was accepted to the Jewish Lyceum on a conditional basis. I was supposed

to stay in the seventh grade at the Montessori School, but when Jewish

children were required to go to Jewish schools, Mr. Elte finally agreed, after a

great deal of persuasion, to accept Lies Goslar and me. Lies also passed this

year, though she has to repeat her geometry exam.

Poor Lies. It isn’t easy for her to study at home; her baby sister, a spoiled

little two-year-old, plays in her room all day. If Gabi doesn’t get her way, she

starts screaming, and if Lies doesn’t look after her, Mrs. Goslar starts

screaming. So Lies has a hard time doing her homework, and as long as that’s

the case, the tutoring she’s been getting won’t help much. The Goslar

household is really a sight. Mrs.

Goslar’s parents live next door, but eat with the family. The there’s a hired

girl, the baby, the always absentminded and absent Mr. Goslar and the always

nervous and irrita Ie Mrs.

Goslar, who’s expecting another baby. Lies, who’s all thumbs, gets lost in themayhem.My sister Margot has also gotten her report card.Brilliant, as usual. If we had such a thing as “cum laude,” she would havepassed with honors, she’s so smart.Father has been home a lot lately. There’s nothing for him to do at the office;it must be awful to feel you’re not needed. Mr. Kleiman has taken overOpekta, and Mr. Kugler, Gies & Co., the company dealing in spices and spicesubstitutes that was set up in 1941.A few days ago, as we were taking a stroll around our neighborhood square,Father began to talk about going into hiding. He said it would be very hardfor us to live cut off from the rest of the world. I asked him why he wasbringing this up now.”Well, Anne,” he replied, “you know that for more than a year we’ve beenbringing clothes, food and furniture to other people. We don’t want ourbelongings to be seized by the Germans. Nor do we want to fall into theirclutches ourselves. So we’ll leave of our own accord and not wait to behauled away.””But when, Father?” He sounded so serious that I felt scared.”Don’t you worry. We’ll take care of everything. just enjoy your carefree lifewhile you can.”That was it. Oh, may these somber words not come true for as long aspossible.The doorbell’s ringing, Hello’s here, time to stop.Yours, AnneWEDNESDAY, JULY 8, 1942Dearest Kitty,It seems like years since Sunday morning. So much has happened it’s as if thewhole world had suddenly turned upside down. But as you can see, Kitty, I’mstill alive, and that’s the main thing, Father says. I’m alive all right, but don’task where or how. You probably don’t understand a word I’m saying today,so I’ll begin by telling you what happened Sunday afternoon.At three o’clock (Hello had left but was supposed to come back later), thedoorbell rang. I didn’t hear it, since I was out on the balcony, lazily reading inthe sun. A little while later Margot appeared in the kitchen doorway lookingvery agitated. “Father has received a call-up notice from the SS,”she whispered. “Mother has gone to see Mr. van Daan” (Mr. van Daan isFather’s business partner and a good friend.) I was stunned. A call-up:everyone knows what that means.Visions of concentration camps and lonely cells raced through my head. Howcould we let Father go to such a fate? “Of course he’s not going,” declaredMargot as we waited for Mother in the living room. “Mother’s gone to Mr.van Daan to ask whether we can move to our hiding place tomorrow. The vanDaans are going with us. There will be seven of us altogether.” Silence. Wecouldn’t speak. The thought of Father off visiting someone in the JewishHospital and completely unaware of what was happening, the long wait forMother, the heat, the suspense — all this reduced us to silence.Suddenly the doorbell rang again. “That’s Hello,” I said.”Don’t open the door!” exclaimed Margot to stop me. But it wasn’t necessary,since we heard Mother and Mr. van Daan downstairs talking to Hello, andthen the two of them came inside and shut the door behind them. Every timethe bell rang, either Margot or I had to tiptoe downstairs to see if it wasFather, and we didn’t let anyone else in. Margot and I were sent from theroom, as Mr. van Daan wanted to talk to Mother alone.When she and I were sitting in our bedroom, Margot told me that the call-upwas not for Father, but for her. At this second shock, I began to cry. Margotis sixteen — apparently they want to send girls her age away on their own.But thank goodness she won’t be going; Mother had said so herself, whichmust be what Father had meant when he talked to me about our going intohiding. Hiding. . . where would we hide?In the city? In the country? In a house? In a shack? When, where, how. . . ?These were questions I wasn’t allowed to ask, but they still kept runningthrough my mind.Margot and I started packing our most important belongings into a schoolbag.The first thing I stuck in was this diary, and then curlers, handkerchiefs,schoolbooks, a comb and some old letters. Preoccupied by the thought ofgoing into hiding, I stuck the craziest things in the bag, but I’m not sorry.Memories mean more to me than dresses.Father finally came hQme around five o’clock, and we called Mr. Kleiman toask if he could come by that evening.Mr. van Daan left and went to get Miep. Miep arrived and promised to returnlater that night, taking with her a bag full of shoes, dresses, jackets,underwear and stockings.After that it was quiet in our apartment; none of us felt like eating. It was stillhot, and everything was very strange.We had rented our big upstairs room to a Mr. Goldschmidt, a divorced manin his thirties, who apparently had nothing to do that evening, since despiteall our polite hints he hung around until ten o’clock.Miep and Jan Gies came at eleven. Miep, who’s worked for Father’s companysince 1933, has become a close friend, and so has her husband Jan. Onceagain, shoes, stockings, books and underwear disappeared into Miep’s bagand Jan’s deep pockets. At eleven-thirty they too disappeared.I was exhausted, and even though I knew it’d be my last night in my own bed,I fell asleep right away and didn’t wake up until Mother called me at fivethirty the next morning.Fortunately, it wasn’t as hot as Sunday; a warm rain fell throughout the day.The four of us were wrapped in so many layers of clothes it looked as if wewere going off to spend the night in a refrigerator, and all that just so wecould take more clothes with us. No Jew in our situation would dare leave thehouse with a suitcase full of clothes. I was wearing two undershirts, threepairs of underpants, a dress, and over that a skirt, a jacket, a raincoat, twopairs of stockings, heavy shoes, a cap, a scarf and lots more. I wassuffocating even before we left the house, but no one bothered to ask me howI felt.Margot stuffed her schoolbag with schoolbooks, went to get her bicycle and,with Miep leading the way, rode off into the great unknown. At any rate,that’s how I thought of it, since I still didn’t know where our hiding place was.At seven-thirty we too closed the door behind us; Moortje, my cat, was theonly living creature I said good-bye to.According to a note we left for Mr. Goldschmidt, she was to be taken to theneighbors, who would give her a good home.The stripped beds, the breakfast things on the table, the pound of meat for thecat in the kitchen — all of these created the impression that we’d left in ahurry. But we weren’t interested in impressions. We just wanted to get out ofthere, to get away and reach our destination in safety.Nothing else mattered.More tomorrow.Yours, AnneTHURSDAY, JULY 9, 1942Dearest Kitty,So there we were, Father, Mother and I, walking in the pouring rain, each ofus with a schoolbag and a shopping bag filled to the brim with the mostvaried assortment of items.The people on their way to work at that early hour gave us sympathetic looks;you could tell by their faces that they were sorry they couldn’t offer us somekind of transportation; the conspicuous yellow star spoke for itself.Only when we were walking down the street did Father and Mother reveal,little by little, what the plan was. For months we’d been moving as much ofour furniture and apparel out of the apartment as we could. It was agreed thatwe’d go into hiding on July 16. Because of Margot’s call-up notice, the planhad to be moved up ten days, which meant we’d have to make do with lessorderly rooms.The hiding place was located in Father’s office building.That’s a little hard for outsiders to understand, so I’ll explain. Father didn’thave a lot of people working in his office, just Mr. Kugler, Mr. Kleiman,Miep and a twenty-three-year-old typist named Bep Voskuijl, all of whomwere informed of our coming. Mr. Voskuijl, Bep’s father, works in thewarehouse, along with two assistants, none of whom were told anything.Here’s a description of the building. The large warehouse on the ground flooris used as a workroom and storeroom and is divided into several differentsections, such as the stockroom and the milling room, where cinnamon,cloves and a pepper substitute are ground.Next to the warehouse doors is another outside’ door, a separate entrance tothe office. Just inside the office door is a second door, and beyond that astairway. At the top of the stairs is another door, with a frosted window onwhich the word “Office” is written in black letters. This is the big front office– very large, very light and very full.Bep, Miep and Mr. Kleiman work there during the day. After passing throughan alcove containing a safe, a wardrobe and a big supply cupboard, you cometo the small, dark, stuffy back office. This used to be shared by Mr. Kuglerand Mr. van Daan, but now Mr. Kugler is its only occupant. Mr. Kugler’soffice can also be reached from the hallway, but only through a glass doorthat can be opened from the inside but not easily from the outside. If youleave Mr. Kugler’s office and proceed through the long, narrow hallway pastthe coal bin and go up four steps, you find yourself in the private office, theshowpiece of the entire building. Elegant mahogany furniture, a linoleumfloor covered with throw rugs, a radio, a fancy lamp, everything first class.Next door is a spacious kitchen with a hot-water heater and two gas burners,and beside that a bathroom. That’s the second floor.A wooden staircase leads from the downstairs hallway to the third floor. Atthe top of the stairs is a landing, with doors on either side. The door on theleft takes you up to the spice storage area, attic and loft in the front part of thehouse. A typically Dutch, very steep, ankle-twisting flight of stairs also runsfrom the front part of the house to another door opening onto the street.The door to the right of the landing leads to the “Secret Annex” at the backofthe house. No one would ever suspect there were so many rooms behindthat plain gray door. There’s just one small step in front of the door, and thenyou’re inside. Straight ahead of you is a steep flight of stairs. To the left is anarrow hallway opening onto a room that serves as the Frank family’s livingINSERT MAP HEREroom and bedroom. Next door is a smaller room, the )edroom and study ofthe two young ladies of the family. ro the right of the stairs is a windowlesswashroom. with a link. The door in the corner leads to the toilet and anotherone to Margot’s and my room. If you go up the itairs and open the door at thetop, you’re surprised to see such a large, light and spacious room in an oldcanalside house like this. It contains a stove (thanks to the fact hat it used tobe Mr. Kugler’s laboratory) and a sink.This will be the kitchen and bedroom of Mr. and Mrs. van Daan, as well asthe general living room, dining room and study for us all. A tiny side room isto be Peter van Daan’s bedroom. Then, just as in the front part of the building,there’s an attic and a loft. So there you are. Now I’ve introduced you to thewhole of our lovely Annex!Yours, Anne

FRIDAY, JULY 10, 1942

Dearest Kitty, I’ve probably bored you with my long description of our house,

but I still think you should know where I’ve ended up; how I ended up here is

something you’ll figure out from my next letters.

But first, let me continue my story, because, as you know, I wasn’t finished.

After we arrived at 263 Prinsengracht, Miep quickly led us through the long

hallway and up the wooden staircase to the next floor and into the Annex.

She shut the door behind us, leaving us alone. Margot had arrived much

earlier on her bike and was waiting for us.

Our living room and all the other rooms were so full of stuff that I can’t find

the words to describe it. All the cardboard boxes that had been sent to the

office in the last few months were piled on the floors and beds. The small

room was filled from floor to cethng with linens. If we wanted to sleep in

properly made beds that night, we had to get going and straighten up the

mess. Mother and Margot were unable to move a muscle. They lay down on

their bare mattresses, tired, miserable and I don’t know what else. But Father

and I, the two cleaner-uppers in the family, started in right away.

All day long we unpacked boxes, filled cupboards, hammered nails and

straightened up the mess, until we fell exhausted into our clean beds at night.

We hadn’t eaten a hot meal all day, but we didn’t care; Mother and Margot

were too tired and keyed up to eat, and Father and I were too busy.

Tuesday morning we started where we left off the night before. Bep and

Miep went grocery shopping with our ration coupons, Father worked on our

blackout screens, we scrubbed the kitchen floor, and were once again busy

from sunup to sundown. Until Wednesday, I didn’t have a chance to think

about the enormous change in my life. Then for the first time since our arrival

in the Secret Annex, I found a moment to tell you all about it and to realize

what had happened to me and what was yet to happen.

Yours, Anne

SATURDAY, JULY 11, 1942

Dearest Kitty,

Father, Mother and Margot still can’t get used to the chiming of the

Westertoren clock, which tells us the time every quarter of an hour. Not me, I

liked it from the start; it sounds so reassuring, especially at night. You no

doubt want to hear what I think of being in hiding. Well, all I can say is that I

don’t really know yet. I don’t think I’ll ever feel at home in this house, but that

doesn’t mean I hate it.

It’s more like being on vacation in some strange pension.

Kind of an odd way to look at life in hiding, but that’s how things are. The

Annex is an ideal place to hide in. It may be damp and lopsided, but there’s

probably not a more comfortable hiding place in all of Amsterdam. No, in all

of Holland.

Up to now our bedroom, with its blank walls, was very bare. Thanks to

Father — who brought my entire postcard and movie-star collection here

beforehand — and to a brush and a pot of glue, I was able to plaster the walls

with pictures.

It looks much more cheerful. When the van Daans arrive, we’ll be able to

build cupboards and other odds and ends out of the wood piled in the attic.

Margot and Mother have recovered somewhat. Yesterday Mother felt well

enough to cook split-pea soup for the first time, but then she was

downstairstalking and forgot all about it. The beans were scorched black, and

no amount of scraping could get them out of the pan.

Last night the four of us went down to the private office and listened to

England on the radio. I was so scared someone might hear it that I literally

begged Father to take me back upstairs. Mother understood my anxiety and

went with me.

Whatever we do, we’re very afraid the neighbors might hear or see us. We

started off immediately the first day sewing curtains. Actually, you can

hardly call them that, since they’re nothing but scraps of fabric, varying

greatly in shape, quality and pattern, which Father and I stitched crookedly

together with unskilled fingers. These works of art were tacked to the

windows, where they’ll stay until we come out of hiding.

The building on our right is a branch of the Keg Company, a firm from

Zaandam, and on the left is a furniture workshop.

Though the people who work there are not on the premises after hours, any

sound we make might travel through the walls. We’ve forbidden Margot to

cough at night, even though she has a bad cold, and are giving her large doses

of codeine.

I’m looking forward to the arrival of the van Daans, which is set for Tuesday.

It will be much more fun and also not as quiet. You see, it’s the silence that

makes me so nervous during the evenings and nights, and I’d give anything to

have one of our helpers sleep here.

It’s really not that bad here, since we can do our own cooking and can listen

to the radio in Daddy’s office.

Mr. Kleiman and Miep, and Bep Voskuijl too, have helped us so much.

We’ve already canned loads of rhubarb, strawberries and cherries, so for the

time being I doubt we’ll be bored.

We also have a supply of reading material, and we’re going to buy lots of

games. Of course, we can’t ever look out the window or go outside. And we

have to be quiet so the people downstairs can’t hear us.

Yesterday we had our hands full. We had to pit two crates of cherries for Mr.

Kugler to can. We’re going to use the empty crates to make bookshelves.

Someone’s calling me.

Yours, Anne

COMMENT ADDED BY ANNE ON SEPTEMBER 2g, 1942: Not beina

able to ao outside upsets me more than I can say, and I’m terrified our hidina

place will be discovered and that we’ll be shot. That, of course, is a fairly

dismal prospect.

SUNDAY, JULY 12, 1942

They’ve all been so nice to me this last month because of my birthday, and

yet every day I feel myself drifting further away from Mother and Margot. I

worked hard today and they praised me, only to start picking on me again

five minutes later.

You can easily see the difference between the way they deal with Margot and

the way they deal with me. For example, Margot broke the vacuum cleaner,

and because of that we’ve been without light for the rest of the day. Mother

said,

“Well, Margot, it’s easy to see you’re not used to working; otherwise, you’d

have known better than to yank the plug out by the cord.” Margot made some

reply, and that was the end of the story.

But this afternoon, when I wanted to rewrite something on Mother’s shopping

list because her handwriting is so hard to read, she wouldn’t let me. She

bawled me out again, and the whole family wound up getting involved.

I don’t fit in with them, and I’ve felt that clearly in the last few weeks. They’re

so sentimental together, but I’d rather be sentimental on my own. They’re

always saying how nice it is with the four of us, and that we get along so

well, without giving a moment’s thought to the fact that I don’t feel that way.

Daddy’s the only one who understands me, now and again, though he usually

sides with Mother and Margot. Another thing I can’t stand is having them talk

about me in front of outsiders, telling them how I cried or how sensibly I’m

behaving. It’s horrible. And sometimes they talk about Moortje and I can’t

take that at all. Moortje is my weak spot. I miss her every minute of the day,

and no one knows how often I think of her; whenever I do, my eyes fill with

tears. Moortje is so sweet, and I love her so much that I keep dreaming she’ll

come back to us.

I have plenty of dreams, but the reality is that we’ll have to stay here until the

war is over. We can’t ever go outside, and the only visitors we can have are

Miep, her husband Jan, Bep Voskuijl, Mr. Voskuijl, Mr. Kugler, Mr.

Kleiman and Mrs. Kleiman, though she hasn’t come because she thinks it’s

too dangerous.

COMMENT ADDED BY ANNE IN SEPTEMBER 1942: Daddy’s always so

nice. He understands me perfectly, and I wish we could have a heart-to-heart

talk sometime without my bursting instantly into tears. But apparently that

has to do with my age. I’d like to spend all my time writing, but that would

probably get boring.

Up to now I’ve only confided my thoughts to my diary. I still haven’t gotten

around to writing amusing sketches that I could read aloud at a later date. In

the future I’m going to devote less time to sentimentality and more time to

reality.

FRIDAY, AUGUST 14, 1942

Dear Kitty,

I’ve deserted you for an entire month, but so little has happened that I can’t

find a newsworthy item to relate every single day. The van Daans arrived on

July 13. We thought they were coming on the fourteenth, but from the

thirteenth to sixteenth the Germans were sending out call-up notices right and

left and causing a lot of unrest, so they decided it would be safer to leave a

day too early than a day too late.

Peter van Daan arrived at nine-thirty in the morning (while we were still at

breakfast). Peter’s going on sixteen, a shy, awkward boy whose company

won’t amount to much. Mr.

and Mrs. van Daan came half an hour later.

Much to our amusement, Mrs. van Daan was carrying a hatbox with a large

chamber pot inside. “I just don’t feel at home without my chamber pot,” she

exclaimed, and it was the first item to find a permanent place under the divan.

Instead of a chamber pot, Mr. van D. was lugging a collapsible tea table

under his arm.

From the first, we ate our meals together, and after three days it felt as if the

seven of us had become one big family.

Naturally, the van Daans had much to tell about the week we’d been away

from civilization. We were especially interested in what had happened to our

apartment and to Mr. Goldschmidt.

Mr. van Daan filled us in: “Monday morning at nine, Mr.

Goldschmidt phoned and asked if I could come over. I went straightaway and

found a very distraught Mr. Goldschmidt. He showed me a note that the

Frank family had left behind. As instructed, he was planning to bring the cat

to the neighbors, which I agreed was a good idea. He was afraid the house

was going to be searched, so we w=nt through all the rooms, straightening up

here and there and clearing the breakfast things off the table. Suddenly I saw

a notepad on Mrs. Frank’s desk, with an address in Maastricht written on it.

Even though I knew Mrs. Frank had left it on purpose, I pretended to be

surprised and horrified and begged Mr.

Goldschmidt to burn this incriminating piece of paper. I swore up and down

that I knew nothing about your disappearance, but that the note had given me

an idea. ‘Mr.

Goldschmidt,’ I said, ‘I bet I know what this address refers to. About six

months ago a high-ranking officer came to the office. It seems he and Mr.

Frank grew up together. He promised to help Mr. Frank if it was ever

necessary. As I recall, he was stationed in Maastricht. I think this officer has

kept his word and is somehow planning to help them cross over to Belgium

and then to Switzerland. There’s no harm in telling this to any friends of the

Franks who come asking about them. Of course, you don’t need to mention

the part about Maastricht.’ And after that I left. This is the story most of your

friends have been told, because I heard it later from several other people.”

We thought it was extremely funny, but we laughed even harder when Mr.

van Daan told us that certain people have vivid imaginations. For example,

one family living on our square claimed they sawall four of us riding by on

our bikes early in the morning, and another woman was absolutely positive

we’d been loaded into some kind of military vehicle in the middle of the

night.

Yours, Anne

FRIDAY, AUGUST 21, 1942

Dear Kitty,

Now our Secret Annex has truly become secret.

Because so many houses are being searched for hidden bicycles, Mr. Kugler

thought it would be better to have a bookcase built in front of the entrance to

our hiding place.

It swings out on its hinges and opens like a door. Mr.

Voskuijl did the carpentry work. (Mr. Voskuijl has been told that the seven of

us are in hiding, and he’s been most helpful.)

Now whenever we want to go downstairs we have to duck and then jump.

After the first three days we were all walking around with bumps on our

foreheads from banging our heads against the low doorway. Then Peter

cushioned it by nailing a towel stuffed with wood shavings to the doorframe.

Let’s see if it helps!

I’m not doing much schoolwork. I’ve given myself a vacation until

September. Father wants to start tutoring me then, but we have to buy all the

books first.

There’s little change in our lives here. Peter’s hair was washed today, but

that’s nothing special. Mr. van Daan and I are always at loggerheads with

each other. Mama always treats me like a baby, which I can’t stand. For the

rest, things are going better. I don’t think Peter’s gotten any nicer. He’s an

obnoxious boy who lies around on his bed all day, only rousing himself to do

a little carpentry work before returning to his nap. What a dope!

Mama gave me another one of her dreadful sermons this morning. We take

the opposite view of everything. Daddy’s a sweetheart; he may get mad at me,

but it never lasts longer than five minutes.

It’s a beautiful day outside, nice and hot, and in spite of everything, we make

the most of the weather by lounging on the folding bed in the attic.

Yours, Anne

COMMENT ADDED BY ANNE ON SEPTEMBER 21, 1942: Mr. van Daan

has been as nice as pie to me recently. I’ve said nothina, but have been

enjoyina it while it lasts.

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 2, 1942

Dearest Kitty,

Mr. and Mrs. van Daan have had a terrible fight. I’ve never seen anything like

it, since Mother and Father wouldn’t dream of shouting at each other like that.

The argument was based on something so trivial it didn’t seem worth wasting

a single word on it. Oh well, to each his own.

Of course, it’s very difficult for Peter, who gets caught in the middle, but no

one takes Peter seriously anymore, since he’s hypersensitive and lazy.

Yesterday he was beside himself with worry because his tongue was blue

instead of pink. This rare phenomenon disappeared as quickly as it came.

Today he’s walking around with a heavy scarf on because he’s got a stiff

neck. His Highness has been complaining of lumbago too. Aches and pains in

his heart, kidneys and lungs are also par for the course. He’s an absolute

hypochondriac!

(That’s the right word, isn’t it?)

Mother and Mrs. van Daan aren’t getting along very well.

There are enough reasons for the friction. To give you one small example,

Mrs. van D. has removed all but three of her sheets from our communal linen

closet. She’s assuming that Mother’s can be used for both families. She’ll be

in for a nasty surprise when she discovers that Mother has followed her lead.

Furthermore, Mrs. van D. is ticked off because we’re using her china instead

of ours. She’s still trying to find out what we’ve done with our plates; they’re a

lot closer than she thinks, since they’re packed in cardboard boxes in the attic,

behind a load of Opekta advertising material. As long as we’re in hiding, the

plates will remain out of her reach.

Since I’m always having accidents, it’s just as well!

Yesterday I broke one of Mrs. van D.’s soup bowls.

“Oh!” she angrily exclaimed. “Can’t you be more careful?

That was my last one.”

Please bear in mind, Kitty, that the two ladies speak abominable Dutch (I

don’t dare comment on the gentlemen: they’d be highly insulted). If you were

to hear their bungled attempts, you’d laugh your head off. We’ve given up

pointing out their errors, since correcting them doesn’t help anyway.

Whenever I quote Mother or Mrs. van Daan, I’ll write proper Dutch instead of

trying to duplicate their speech.

Last week there was a brief interruption in our monotonous routine. This was

provided by Peter — and a book about women. I should explain that Margot

and Peter are allowed to read nearly all the books Mr. Kleiman lends us. But

the adults preferred to keep this special book to themselves.

This immediately piqued Peter’s curiosity. What forbidden fruit did it

contain? He snuck off with it when his mother was downstairs talking, and

took himself and his booty to the loft. For two days all was well. Mrs. van

Daan knew what he was up to, but kept mum until Mr. van Daan found out

about it. He threw a fit, took the book away and assumed that would be the

end of the business. However, he’d neglected to take his son’s curiosity into

account. Peter, not in the least fazed by his father’s swift action, began

thinking up ways to read the rest of this vastly interesting book.

In the meantime, Mrs. van D. asked Mother for her opinion.

Mother didn’t think this particular book was suitable for Margot, but she saw

no harm in letting her read most other books.

You see, Mrs. van Daan, Mother Said, there’s a big difference between

Margot and Peter. To begin with, Margot’s a girl, and girls are always more

mature than boys. Second, she’s already read many serious books and doesn’t

go looking for those which are no longer forbidden. Third, Margot’s much

more sensible and intellectually advanced, as a result of her four years at an

excellent school.”

Mrs. van Daan agreed with her, but felt it was wrong as a matter of principle

to let youngsters read books written for adults.

Meanwhile, Peter had thought of a suitable time when no one would be

interested in either him or the book. At seven-thirty in the evening, when the

entire family was listening to the radio in the private office, he took his

treasure and stole off to the loft again. He should have been back by eightthirty, but he was so engrossed in the book that he forgot the time and was

just coming down the stairs when his father entered the room. The scene that

followed was not surprising: after a slap, a whack and a tug-of-war, the book

lay on the table and Peter was in the loft.

This is how matters stood when it was time for the family to eat. Peter stayed

upstairs. No one gave him a moment’s thought; he’d have to go to bed without

his dinner. We continued eating, chatting merrily away, when suddenly we

heard a piercing whistle. We lay down our forks and stared at each other, the

shock clearly visible on our pale faces.

Then we heard Peter’s voice through the chimney: “I won t come down!”

Mr. van Daan leapt up, his napkin falling to the floor, and shouted, with the

blood rushing to his face, “I’ve had enough!”

Father, afraid of what might happen, grabbed him by the arm and the two

men went to the attic. After much struggling and kicking, Peter wound up in

his room with the door shut, and we went on eating.

Mrs. van Daan wanted to save a piece of bread for her darling son, but Mr.

van D. was adamant. “If he doesn’t apologize this minute, he’ll have to sleep

in the loft.”

We protested that going without dinner was enough punishment. What if

Peter were to catch cold? We wouldn’t be able to call a doctor.

Peter didn’t apologize, and returned to the loft.

Mr. van Daan decided to leave well enough alone, though he did note the

next morning that Peter’s bed had been slept in.

At seven Peter went to the attic again, but was persuaded to come downstairs

when Father spoke a few friendly words to him. After three days of sullen

looks and stubborn silence, everything was back to normal.

Yours, Anne

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1942

Dearest Kitty,

Today I’ll tell you the general news here in the Annex. A lamp has been

mounted above my divan bed so that in the future, when I hear the guns

going off, I’ll be able to pull a cord and switch on the light. I can’t use it at the

moment because we’re keeping our window open a little, day and night.

The male members of the van Daan contingent have built a very handy woodstained food safe, with real screens. Up to now this glorious cupboard has

been located in Peter’s room, but in the interests of fresh air it’s been moved

to the attic. Where it once stood, there’s now a shelf. I advised Peter to put his

table underneath the shelf, add a nice rug and hang his own cupboard where

the table now stands. That might make his little cubbyhole more comfy,

though I certainly wouldn’t like to sleep there.

Mrs. van Daan is unbearable. I’m continually being scolded for my incessant

chatter when I’m upstairs. I simply let the words bounce right off me!

Madame now has a new trick up her sleeve: trying to get out of washing the

pots and pans. If there’s a bit of food left at the bottom of the pan, she leaves

it to spoil instead of transferring it to a glass dish. Then in the afternoon when

Margot is stuck with cleaning all the pots and pans, Madame exclaims, “Oh,

poor Margot, you have so much work to do!”

Every other week Mr. Kleiman brings me a couple of books written for girls

my age. I’m enthusiastic about the loop ter Heul series. I’ve enjoyed all of

Cissy van Marxveldt’s books very much. I’ve read The Zaniest Summer four

times, and the ludicrous situations still make me laugh.

Father and I are currently working on our family tree, and he tells me

something about each person as we go along. I’ve begun my schoolwork. I’m

working hard at French, cramming five irregular verbs into my head every

day. But I’ve forgotten much too much of what I learned in school.

Peter has taken up his English with great reluctance. A few schoolbooks have

just arrived, and I brought a large supply of notebooks, pencils, erasers and

labels from home.

Pim (that’s our pet name for Father) wants me to help him with his Dutch

lessons. I’m perfectly willing to tutor him in exchange for his assistance with

French and other subjects.

But he makes the most unbelievable mistakes!

I sometimes listen to the Dutch broadcasts from London.

Prince Bernhard recently announced that Princess juliana is expecting a baby

in January, which I think is wonderful. No one here understands why I take

such an interest in the Royal Family.

A few nights ago I was the topic of discussion, and we all decided I was an

ignoramus. As a result, I threw myself into my schoolwork the next day,

since I have little desire to still be a freshman when I’m fourteen or fifteen.

The fact that I’m hardly allowed to read anything was also discussed.

At the moment, Mother’s reading Gentlemen, Wives and Servants, and of

course I’m not allowed to read it (though Margot is!). First I have to be more

intellectually developed, like my genius of a sister. Then we discussed my

ignorance of philosophy, psychology and physiology (I immediately looked

up these big words in the dictionary!).

It’s true, I don’t know anything about these subjects. But maybe I’ll be smarter

next year!

I’ve come to the shocking conclusion that I have only one long-sleeved dress

and three cardigans to wear in the winter.

Father’s given me permission to knit a white wool sweater; the yarn isn’t very

pretty, but it’ll be warm, and that’s what counts. Some of our clothing was left

with friends, but unfortunately we won’t be able to get to it until after the war.

Provided it’s still there, of course.

I’d just finished writing something about Mrs. van Daan when she walked

into the room. Thump, I slammed the book shut.

“Hey, Anne, can’t I even take a peek?”

“No, Mrs. van Daan.”

“Just the last page then?”

“No, not even the last page, Mrs. van Daan.”

Of course, I nearly died, since that particular page contained a rather

unflattering description of her.

There’s something happening every day, but I’m too tired and lazy to write it

all down.

Yours, Anne

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 1942

Dearest Kitty,

Father has a friend, a man in his mid-seventies named Mr.

Dreher, who’s sick, poor and deaf as a post. At his side, like a useless

appendage, is his wife, twenty-seven years younger and equally poor, whose

arms and legs are loaded with real and fake bracelets and rings left over from

more prosperous days. This Mr. Dreher has already been a great nuisance to

Father, and I’ve always admired the saintly patience with which he handled

this pathetic old man on the phone. When we were still living at home,

Mother used to advise him to put a gramophone in front of the receiver, one

that would repeat every three minutes, “Yes, Mr. Dreher” and

“No, Mr. Dreher,” since the old man never understood a word of Father’s

lengthy replies anyway.

Today Mr. Dreher phoned the office and asked Mr. Kugler to come and see

him. Mr. Kugler wasn’t in the mood and said he would send Miep, but Miep

canceled the appointment. Mrs.

Dreher called the office three times, but since Miep was reportedly out the

entire afternoon, she had to imitate Bep’s voice. Downstairs in the office as

well as upstairs in the Annex, there was great hilarity. Now each time the

phone rings, Bep says’ ‘That’s Mrs. Dreher!” and Miep has to laugh, so that

the people on the other end of the line are greeted with an impolite giggle.

Can’t you just picture it? This has got to be the greatest office in the whole

wide world. The bosses and the office girls have such fun together!

Some evenings I go to the van Daans for a little chat. We eat “mothball

cookies” (molasses cookies that were stored in a closet that was mothproofed)

and have a good time. Recently the conversation was about Peter. I said that

he often pats me on the cheek, which I don’t like. They asked me in a

typically grown-up way whether I could ever learn to love Peter like a

brother, since he loves me like a sister. “Oh, no!” I said, but what I was

thinking was, “Oh, ugh!” Just imagine! I added that Peter’s a bit stiff, perhaps

because he’s shy. Boys who aren’t used to being around girls are like that.

I must say that the Annex Committee (the men’s section) is very creative.

Listen to the scheme they’ve come up with to get a message to Mr. Broks, an

Opekta Co. sales representative and friend who’s surreptitiously hidden some

of our things for us! They’re going to type a letter to a store owner in southern

Zealand who is, indirectly, one of Opekta’ s customers and ask him to fill out

a form and send it back in the enclosed self-addressed envelope. Father will

write the address on the envelope himself. Once the letter is returned from

Zealand, the form can be removed and a handwritten message confirming that

Father is alive can be inserted in the envelope. This way Mr. Broks can read

the letter without suspecting a ruse. They chose the province of Zealand

because it’s close to Belgium (a letter can easily be smuggled across the

border) and because no one is allowed to travel there without a special

permit. An ordinary salesman like Mr. Broks would never be granted a

permit.

Yesterday Father put on another act. Groggy with sleep, he stumbled off to

bed. His feet were cold, so I lent him my bed socks. Five minutes later he

flung them to the floor. Then he pulled the blankets over his head because the

light bothered him. The lamp was switched off, and he gingerly poked his

head out from under the covers. It was all very amusing. We started talking

about the fact that Peter says Margot is a

“buttinsky.” Suddenly Daddy’s voice was heard from the depths: “Sits on her

butt, you mean.

Mouschi, the cat, is becoming nicer to me as time goes by, but I’m still

somewhat afraid of her.

Yours, Anne

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 1942

Dearest Kitty,

Mother and I had a so-called “discussion” today, but the annoying part is that

I burst into tears. I can’t help it.

Daddy is always nice to me, and he also understands me much better. At

moments like these I can’t stand Mother. It’s obvious that I’m a stranger to

her; she doesn’t even know what I think about the most ordinary things.

We were talking about maids and the fact that you’re supposed to refer to

them as “domestic help” these days. She claimed that when the war is over,

that’s what they’ll want to be called. I didn’t quite see it that way. Then she

added that I talk about’ ‘later” so often and that I act as if I were such a lady,

even though I’m not, but I don’t think building sand castles in the air is such a

terrible thing to do, as long as you don’t take it too seriously. At any rate,

Daddy usually comes to my defense. Without him I wouldn’t be able to stick

it out here.

I don’t get along with Margot very well either. Even though our family never

has the same kind of outbursts they have upstairs, I find it far from pleasant.

Margot’s and Mother’s personalities are so alien to me. I understand my

girlfriends better than my own mother. Isn’t that a shame?

For the umpteenth time, Mrs. van Daan is sulking. She’s very moody and has

been removing more and more of her belongings and locking them up. It’s too

bad Mother doesn’t repay every van Daan “disappearing act” with a Frank

“disappearing act.”